by Jochen Szangolies

The previous column left us with the tantalizing possibility of connecting Gödelian undecidability to quantum mechanical indeterminacy. At this point, however, we need to step back a little.

Gödel’s result inhabits the rarefied realm of mathematical logic, with its crisply stated axioms and crystalline, immutable truths. It is not at all clear whether it should have any counterpart in the world of physics, where ultimately, experiment trumps pure reason.

However, there is a broad correspondence between physical and mathematical systems: in each case, we start with some information—the axioms or the initial state—apply a certain transformation—drawing inferences or evolving the system in time—and end up with new information—the theorem to be proved, or the system’s final state. An analogy to undecidability then would be an endpoint that can’t be reached—a theorem that can’t be proven, or a cat whose fate remains uncertain.

Perhaps this way of putting it looks familiar: there is another class of systems that obeys this general structure, and which were indeed the first point of contact of undecidability with the real world—namely, computers. A computer takes initial data (an input), performs a transformation (executes a program), and produces a result (the output). Moreover, computers are physical devices: concrete machines carrying out computations. And as it turns out, there exists questions about these devices that are undecidable. Read more »

A few months ago, I wrote about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Spring and how his focus in this book is the examination of two worlds: the physical world that exists apart from us (the outside world), and the world of meaning and significance that is overlaid on top of this world through language and consciousness (the inner world). Knausgaard’s main goal seems to be to shock us out of our habitual, unreflective existence, and to bring about an awareness with which we can experience our lives in a different way.

A few months ago, I wrote about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Spring and how his focus in this book is the examination of two worlds: the physical world that exists apart from us (the outside world), and the world of meaning and significance that is overlaid on top of this world through language and consciousness (the inner world). Knausgaard’s main goal seems to be to shock us out of our habitual, unreflective existence, and to bring about an awareness with which we can experience our lives in a different way. In memory we are standing in the kitchen of the Treman Cottage at Breadloaf. It is late afternoon in the summer of 1976 and I have brought my copies of Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk and Dismantling the Silence for Charles Simic to sign. He is slouching a bit, leaning against the counter, and seems genuinely touched that I had carried the books, deeply penciled and dog-eared, all the way from home.

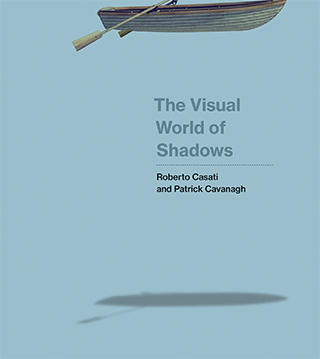

In memory we are standing in the kitchen of the Treman Cottage at Breadloaf. It is late afternoon in the summer of 1976 and I have brought my copies of Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk and Dismantling the Silence for Charles Simic to sign. He is slouching a bit, leaning against the counter, and seems genuinely touched that I had carried the books, deeply penciled and dog-eared, all the way from home. Painters have long struggled with the difficulties of depicting shadows, so much so that shadows — after a brief, spectacular showcase in ancient Roman paintings and mosaics — are almost absent from pictorial art up to the Renaissance and then are hardly present outside traditional Western art.

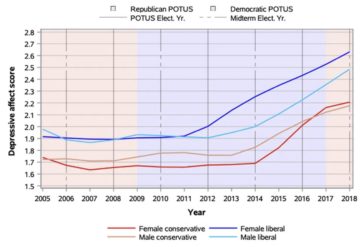

Painters have long struggled with the difficulties of depicting shadows, so much so that shadows — after a brief, spectacular showcase in ancient Roman paintings and mosaics — are almost absent from pictorial art up to the Renaissance and then are hardly present outside traditional Western art. Earlier this month the CDC released the results of its Youth Risk Behavior Survey of American teenagers. The findings have been much discussed, with the focus largely and understandably on the fact that

Earlier this month the CDC released the results of its Youth Risk Behavior Survey of American teenagers. The findings have been much discussed, with the focus largely and understandably on the fact that  I

I To get the inside story behind the chatbot—how it was made, how OpenAI has been updating it since release, and how its makers feel about its success—I talked to four people who helped build what has become

To get the inside story behind the chatbot—how it was made, how OpenAI has been updating it since release, and how its makers feel about its success—I talked to four people who helped build what has become  In this week’s New Yorker, the contributing writer Merve Emre

In this week’s New Yorker, the contributing writer Merve Emre  Devaka Gunawardena , Niyanthini Kadirgamar, and Ahilan Kadirgamar in Phenomenal World:

Devaka Gunawardena , Niyanthini Kadirgamar, and Ahilan Kadirgamar in Phenomenal World: Perry Anderson in New Left Review:

Perry Anderson in New Left Review: Kenda Mutongi in Boston Review:

Kenda Mutongi in Boston Review: Dylan Saba in Jewish Currents:

Dylan Saba in Jewish Currents: W

W