Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò in Aeon:

We should expunge, forever, the epithet ‘precolonial’ or any of its cognates from all aspects of the study of Africa and its phenomena. We should banish title phrases, names and characterisations of reality and ideas containing the word.

We should expunge, forever, the epithet ‘precolonial’ or any of its cognates from all aspects of the study of Africa and its phenomena. We should banish title phrases, names and characterisations of reality and ideas containing the word.

To those who might be put off by the severity of the proposal, or its ideological-police ring, I hear you and ask only that, with just a little patience, you hear me out. It will not take much to jolt us out of the present unthinking in assuming that ‘precolonial’ or ‘traditional’, and ‘indigenous’, has any worthwhile role to play in our attempt to track, describe, explain and make sense of African life and history.

When ‘precolonial’ is used for describing African ideas, processes, institutions and practices, through time, it misrepresents them. When deployed to explain African experience and institutions, and characterise the logic of their evolution through history, it is worthless and theoretically vacuous. The concept of ‘precolonial’ anything hides, it never discloses; it obscures, it never illuminates; it does not aid understanding in any manner, shape or form.

More here.

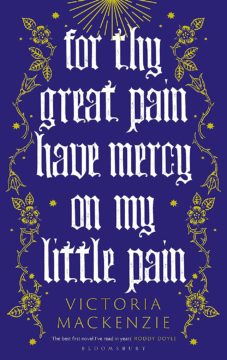

The game is rigged. It is rigged like capitalism is rigged. There is no puppet master, no conspiracy, only a field where advantages, to begin with, are distributed unequally. You can beat the long odds, but you have long odds to beat; a team of scholars has been working for almost 10 years to detail exactly how the rigging works. Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young, later joined by Claire Grossman, began by noticing that poetry readings they regularly attended were held in “mainly white rooms.” They wanted to know why. To find out, they would need to widen their purview. The wider they went, the hungrier they became to understand who gets to succeed as a writer in the United States today. They wanted to reveal the system, to see all of it.

The game is rigged. It is rigged like capitalism is rigged. There is no puppet master, no conspiracy, only a field where advantages, to begin with, are distributed unequally. You can beat the long odds, but you have long odds to beat; a team of scholars has been working for almost 10 years to detail exactly how the rigging works. Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young, later joined by Claire Grossman, began by noticing that poetry readings they regularly attended were held in “mainly white rooms.” They wanted to know why. To find out, they would need to widen their purview. The wider they went, the hungrier they became to understand who gets to succeed as a writer in the United States today. They wanted to reveal the system, to see all of it. I

I The field is all but clear now, and it seems safe to say that the two most important long-form journalists this country produced in the second half of the last century were Joan Didion and Janet Malcolm. Their differences are more evident than their similarities: the cold Los Angeles burn of Didion’s work, the measured New York ambiguity of Malcolm’s. Still, perhaps it’s no accident that both were white women, marginalized by definition, yet not so strictly that it prevented either from slipping into the mainstream as witness, as recorder. Both were born in 1934, and both died in 2021. A world goes with them.

The field is all but clear now, and it seems safe to say that the two most important long-form journalists this country produced in the second half of the last century were Joan Didion and Janet Malcolm. Their differences are more evident than their similarities: the cold Los Angeles burn of Didion’s work, the measured New York ambiguity of Malcolm’s. Still, perhaps it’s no accident that both were white women, marginalized by definition, yet not so strictly that it prevented either from slipping into the mainstream as witness, as recorder. Both were born in 1934, and both died in 2021. A world goes with them. Herman Mark Schwartz in Progressive International:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Progressive International: Justin E. H. Smith in Unherd:

Justin E. H. Smith in Unherd: Jeremy Walton in Sidecar (image credit: Stable Diffusion):

Jeremy Walton in Sidecar (image credit: Stable Diffusion): Daniel Driscoll in Phenomenal World’s Polycrisis (image credit: Stable Diffusion):

Daniel Driscoll in Phenomenal World’s Polycrisis (image credit: Stable Diffusion): T

T Rome, 1950: The diary begins innocently enough, with the name of its owner, Valeria Cossati, written in a neat script.

Rome, 1950: The diary begins innocently enough, with the name of its owner, Valeria Cossati, written in a neat script. When British brain surgeon Henry Marsh sat down beside his patient’s bed following surgery, the bad news he was about to deliver stemmed from his own mistake. The man had a trapped nerve in his arm that required an operation – but after making a midline incision in his neck,

When British brain surgeon Henry Marsh sat down beside his patient’s bed following surgery, the bad news he was about to deliver stemmed from his own mistake. The man had a trapped nerve in his arm that required an operation – but after making a midline incision in his neck,  Animals that produce many offspring tend to have short lives, while less prolific species tend to live longer. Cockroaches lay hundreds of eggs while living less than a year. Mice have dozens of babies during their year or two of life. Humpback whales produce only one calf every two or three years and live for decades. The rule of thumb seems to reflect evolutionary strategies that channel nutritional resources either into reproducing quickly or into growing more robust for a long-term advantage.

Animals that produce many offspring tend to have short lives, while less prolific species tend to live longer. Cockroaches lay hundreds of eggs while living less than a year. Mice have dozens of babies during their year or two of life. Humpback whales produce only one calf every two or three years and live for decades. The rule of thumb seems to reflect evolutionary strategies that channel nutritional resources either into reproducing quickly or into growing more robust for a long-term advantage. A carefully administered and properly controlled dosage of a hallucinogen, their studies attest, can accomplish in a single, not-to-be-repeated session what years of psychotherapy and regimens of antidepressant medications often fail to achieve.

A carefully administered and properly controlled dosage of a hallucinogen, their studies attest, can accomplish in a single, not-to-be-repeated session what years of psychotherapy and regimens of antidepressant medications often fail to achieve. A boyfriend just going through the motions. A spouse worn into the rut of habit. A jetlagged traveler’s message of exhaustion-fraught longing. A suppressed kiss, unwelcome or badly timed. These were some of the interpretations that reverberated in my brain after I viewed a

A boyfriend just going through the motions. A spouse worn into the rut of habit. A jetlagged traveler’s message of exhaustion-fraught longing. A suppressed kiss, unwelcome or badly timed. These were some of the interpretations that reverberated in my brain after I viewed a