Teresa Xie in Vox:

At the end of my sophomore year of college, I found myself at a career crossroads. The pandemic hit a few months earlier and like most students across the country, I was kicked off campus and sent back home. As I spent the remainder of the school year sitting idly in my childhood bedroom, I had no choice but to wrestle with the ever-looming question: What do I really want to do with my life?

At the end of my sophomore year of college, I found myself at a career crossroads. The pandemic hit a few months earlier and like most students across the country, I was kicked off campus and sent back home. As I spent the remainder of the school year sitting idly in my childhood bedroom, I had no choice but to wrestle with the ever-looming question: What do I really want to do with my life?

Media and culture had always been passions of mine, but I never saw them as viable paths to pursue. But the dreariness of the pandemic shook me, and I decided to pivot from business to journalism with no portfolio, no connections, and no experience during what seemed like the most inopportune time to make a career switch. The only resource I had at my disposal was the internet — and turns out, I didn’t need much more. Over the next few weeks, I scoured the depths of Twitter — reading profiles of journalists my age and seasoned writers with dream gigs. I figured the best way to learn more about the industry was to actually talk to people who were in it. I cold Twitter-DM’d anyone I thought was remotely interesting and asked to hop on the phone with them. To my surprise, not one person refused — and through these conversations I learned about programs to apply to, editors to pitch to, and other writers I should try to talk to.

More here.

Tours have always been good for getting me out of my bubble, this one even more so. Driving across the Midwest, I saw one Trump 2024 sign after another—this while the election was an entire three years away. “You know you’re in a place that’s inhospitable to liberals when you see fireworks stores,” Adam said in rural Indiana as we passed one powder keg after another.

Tours have always been good for getting me out of my bubble, this one even more so. Driving across the Midwest, I saw one Trump 2024 sign after another—this while the election was an entire three years away. “You know you’re in a place that’s inhospitable to liberals when you see fireworks stores,” Adam said in rural Indiana as we passed one powder keg after another. W

W According to poetry scholar John Timberman Newcomb, Millay is “

According to poetry scholar John Timberman Newcomb, Millay is “ The founders of statistical mechanics in the 19th century faced an uphill battle to convince their fellow physicists that the laws of thermodynamics could be derived from the random motions of microscopic atoms. This insight turns out to be even more important than they realized: the emergence of patterns characterizing our macroscopic world relies crucially on the increase of entropy over time. Barry Loewer has (in collaboration with David Albert) been developing a theory of the

The founders of statistical mechanics in the 19th century faced an uphill battle to convince their fellow physicists that the laws of thermodynamics could be derived from the random motions of microscopic atoms. This insight turns out to be even more important than they realized: the emergence of patterns characterizing our macroscopic world relies crucially on the increase of entropy over time. Barry Loewer has (in collaboration with David Albert) been developing a theory of the  Nothing destroys progress like conflict. Fighting massacres soldiers, ravages civilians, starves cities, plunders stores, disrupts trade, demolishes industry, and bankrupts governments. It undermines economic growth in indirect ways too. Most people and business won’t do the basic activities that lead to development when they expect bombings, ethnic cleansing, or arbitrary justice; they won’t specialize in tasks, trade, invest their wealth, or develop new ideas. These costs of war incentivize rivals to steer clear from prolonged and intense violence.

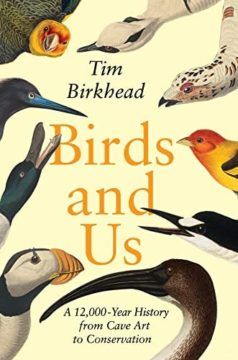

Nothing destroys progress like conflict. Fighting massacres soldiers, ravages civilians, starves cities, plunders stores, disrupts trade, demolishes industry, and bankrupts governments. It undermines economic growth in indirect ways too. Most people and business won’t do the basic activities that lead to development when they expect bombings, ethnic cleansing, or arbitrary justice; they won’t specialize in tasks, trade, invest their wealth, or develop new ideas. These costs of war incentivize rivals to steer clear from prolonged and intense violence. Relationships between ancient humans and birds had a deeply religious element. Birkhead locates the “ground zero” of an early human civilization built around animal worship in ancient Egypt. Within the catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel in Egypt, there are four million mummified birds contained in jars and coffins. In addition to mummifying ibises, ancient Egyptians preserved a variety of creatures in cemeteries throughout the Nile Valley. Birds, however, are among the most prominent animals. Clearly, the lovingly embalmed birds were considered sacred; and ancient Egypt was a civilization in which humans and birds lived in harmony.

Relationships between ancient humans and birds had a deeply religious element. Birkhead locates the “ground zero” of an early human civilization built around animal worship in ancient Egypt. Within the catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel in Egypt, there are four million mummified birds contained in jars and coffins. In addition to mummifying ibises, ancient Egyptians preserved a variety of creatures in cemeteries throughout the Nile Valley. Birds, however, are among the most prominent animals. Clearly, the lovingly embalmed birds were considered sacred; and ancient Egypt was a civilization in which humans and birds lived in harmony. Protests enter their second week. I’m waiting on the street for the taxi to arrive when I see an old religious man coming towards me. At first, I’m afraid he wants to mention I’m not wearing a hijab. All of a sudden, he brings his phone in front of me and shows me Mahsa Amini’s photo, saying, “Can you believe it, ma’am? They killed someone’s daughter. I myself have a daughter. I swear to God, I haven’t slept for a week.”

Protests enter their second week. I’m waiting on the street for the taxi to arrive when I see an old religious man coming towards me. At first, I’m afraid he wants to mention I’m not wearing a hijab. All of a sudden, he brings his phone in front of me and shows me Mahsa Amini’s photo, saying, “Can you believe it, ma’am? They killed someone’s daughter. I myself have a daughter. I swear to God, I haven’t slept for a week.” Ned and Sunny stretch out together on the warm sand. He rests his head on her back, and every so often he might give her an affectionate nudge with his nose. The pair is quiet and, like many long-term couples, they seem perfectly content just to be in each other’s presence.

Ned and Sunny stretch out together on the warm sand. He rests his head on her back, and every so often he might give her an affectionate nudge with his nose. The pair is quiet and, like many long-term couples, they seem perfectly content just to be in each other’s presence.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.  A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

It was announced last week that scientists have integrated neurons from human brains into infant rat brains, resulting in new insights about how our brain cells grow and connect, and some hope of a deeper understanding of neural disorders.

It was announced last week that scientists have integrated neurons from human brains into infant rat brains, resulting in new insights about how our brain cells grow and connect, and some hope of a deeper understanding of neural disorders.