Month: June 2022

Does Hungary Offer a Glimpse of Our Authoritarian Future?

Andrew Marantz in The New Yorker:

The Republican Party hasn’t adopted a new platform since 2016, so if you want to know what its most influential figures are trying to achieve—what, exactly, they have in mind when they talk about an America finally made great again—you’ll need to look elsewhere for clues. You could listen to Donald Trump, the Party’s de-facto standard-bearer, except that nobody seems to have a handle on what his policy goals are, not even Donald Trump. You could listen to the main aspirants to his throne, such as Governor Ron DeSantis, of Florida, but this would reveal less about what they’re for than about what they’re against: overeducated élites, apart from themselves and their allies; “wokeness,” whatever they’re taking that to mean at the moment; the overzealous wielding of government power, unless their side is doing the wielding. Besides, one person can tell you only so much. A more efficient way to gauge the current mood of the Party is to spend a weekend at the Conservative Political Action Conference, better known as cpac.

The Republican Party hasn’t adopted a new platform since 2016, so if you want to know what its most influential figures are trying to achieve—what, exactly, they have in mind when they talk about an America finally made great again—you’ll need to look elsewhere for clues. You could listen to Donald Trump, the Party’s de-facto standard-bearer, except that nobody seems to have a handle on what his policy goals are, not even Donald Trump. You could listen to the main aspirants to his throne, such as Governor Ron DeSantis, of Florida, but this would reveal less about what they’re for than about what they’re against: overeducated élites, apart from themselves and their allies; “wokeness,” whatever they’re taking that to mean at the moment; the overzealous wielding of government power, unless their side is doing the wielding. Besides, one person can tell you only so much. A more efficient way to gauge the current mood of the Party is to spend a weekend at the Conservative Political Action Conference, better known as cpac.

On a Friday in February, I arrived at the Rosen Shingle Creek resort, in Orlando. It was a temperate afternoon, and the Party faithful were spending it indoors, in the air-conditioning. I

More here.

A Psychedelic Renaissance at the V.A.

Ernesto Londono in The New York Times:

The last known experiment at a Department of Veterans Affairs clinic with psychedelic-assisted therapy started in 1963. That was the year President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. “Surfin’ U.S.A.” topped the music charts, and American troops had not yet deployed to Vietnam.

The last known experiment at a Department of Veterans Affairs clinic with psychedelic-assisted therapy started in 1963. That was the year President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. “Surfin’ U.S.A.” topped the music charts, and American troops had not yet deployed to Vietnam.

At the time, the federal government was a hotbed of psychedelics research. The C.I.A. explored using LSD as a mind-control tool against adversaries. The U.S. Army tested the drug’s potential to incapacitate enemies on the battlefield. And the V.A. used it in an experimental study to treat alcoholism.

But booming recreational use of drugs, including hallucinogens, sparked a fierce political backlash and helped set in motion the war on drugs, which, among other things, ended an era of research into the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Unfettered

I relinquished you more times

than I can count. Holding on

is too risky. A tight grasp

drains the container, leaving its contents

empty. My fingers poised for release,

both hands curled against your back,

I expect nothing. Anything more

is an offering. You have learned to give

for the first time in decades.

I must learn to receive.

by Leah Mueller

Passing Through: On Leonard Cohen

Andrew Martin at The Paris Review:

When Leonard Cohen starts singing “Passing Through” on his 1973 Live Songs album, he sounds tentative, like a child who’s been asked to sing a song he learned at school in front of a party of adults. “I saw Jesus on the cross, on a hill called calvary … ” On the record his voice is faint—I’ve spent twenty years turning up the volume—and he sings so casually that it sounds like he really might have seen the crucified Christ, and asked him, deadpan and impertinent, “Do you hate mankind, for what he’s done to you?” Jesus has a pretty mellow, Jesus-like response, delivered in Cohen’s increasingly confident baritone: “He said ‘Talk of love not hate—things to do, it’s getting late.’” He is, like the rest of the Biblical and historical characters Cohen will encounter throughout the song, only passing through. Compare Cohen’s line readings to the declamatory, bugged-out delivery that Dylan gives to the opening lines of his bible pastiche “Highway 61 Revisited.” Cohen is calm, weary, a little resigned; Dylan is providing color commentary at the Belmont Stakes.

When Leonard Cohen starts singing “Passing Through” on his 1973 Live Songs album, he sounds tentative, like a child who’s been asked to sing a song he learned at school in front of a party of adults. “I saw Jesus on the cross, on a hill called calvary … ” On the record his voice is faint—I’ve spent twenty years turning up the volume—and he sings so casually that it sounds like he really might have seen the crucified Christ, and asked him, deadpan and impertinent, “Do you hate mankind, for what he’s done to you?” Jesus has a pretty mellow, Jesus-like response, delivered in Cohen’s increasingly confident baritone: “He said ‘Talk of love not hate—things to do, it’s getting late.’” He is, like the rest of the Biblical and historical characters Cohen will encounter throughout the song, only passing through. Compare Cohen’s line readings to the declamatory, bugged-out delivery that Dylan gives to the opening lines of his bible pastiche “Highway 61 Revisited.” Cohen is calm, weary, a little resigned; Dylan is providing color commentary at the Belmont Stakes.

more here.

Hilary Putnam on the Depths & Shallows of Experience

Abort All Thought That Life Begins

by Mike Bendzela

One tedious outcome of the ascendance of the anti-abortion movement in the United States is having to listen to the tiresome arguments about “the beginning of [human] life.” It’s like being stuck in a dentist’s office waiting for an appointment while nauseating top-forty hits from the 1970s play on a hidden radio.

Not this shit again.

Abortion is an issue my husband and I have never had, nor will ever have to be concerned about, given that neither of us has a uterus. Nor do we have children from previous engagements, who might have to be concerned about what to do with unwanted or malformed zygotes/ blastocysts/ embryos/ fetuses. But the subject is still interesting to me, given that I have existed as each of those entities at one time or another. Read more »

Monday Poem

Umwelt

what I can perceive is the outer limit of what I am

there is a universe of unknown dimensions

it whirls about me but is not about me

I am constrained

I ride its hub

Jim Culleny

6/22/22

How the Industrial Revolution Played Favorites

by Rebecca Baumgartner

In his book Enlightenment Now, when discussing the drastic improvements in quality of life over the past several decades, Steven Pinker says that “the liberation of humankind from household labor is in practice the liberation of women from household labor. Perhaps the liberation of women in general.” The most exciting promise of technology is that it will make being a human slightly less terrible. In the case of household appliances, the claim is that they will make being a woman slightly less terrible.

In his book Enlightenment Now, when discussing the drastic improvements in quality of life over the past several decades, Steven Pinker says that “the liberation of humankind from household labor is in practice the liberation of women from household labor. Perhaps the liberation of women in general.” The most exciting promise of technology is that it will make being a human slightly less terrible. In the case of household appliances, the claim is that they will make being a woman slightly less terrible.

Once women gained access to new labor-saving devices, the story goes, they were liberated from drudgery. We all seemingly agree that these innovations have given us our time back, shifting the role of the home from a place of production to a place of consumption. What used to be produced at home (often by women) is now purchased outside the home in the form of goods and services. Everybody wins! Progress has leveled the playing field and given women so much free time that they’re at liberty to enter the workforce in historically unprecedented numbers.

Well, hang on a minute. If these devices were supposed to create so much free time and lead to “the liberation of women in general,” then why do women continue to do significantly more household labor than men? Read more »

We Should Fix Climate Change, But We Should Not Regret It

by Thomas R. Wells

Climate change is a huge and urgent problem. It is natural to suppose that it is therefore a terrible mistake, an unforced error that we should regret and try to prevent ever happening again.

Climate change is a huge and urgent problem. It is natural to suppose that it is therefore a terrible mistake, an unforced error that we should regret and try to prevent ever happening again.

I disagree. Climate change is the unfortunate outcome of the economic growth that has transformed human civilisation for the better. We cannot regret climate change without regretting the vastly better world for most people that the fossil-fuel powered industrial revolution brought. Nor should we draw the anti-technology lesson that solutions are always worse than the original problems, that humans should retreat to living within the bounds of nature rather than attempting to escape them.

The argument I am trying to oppose is not often made explicitly, but seems to lurk around and underneath the response to climate change, especially among people younger than me. It looks something like this:

P1. Climate change is a huge and urgent problem

P2. Climate change is human-made, the result of the industrial revolution and the striving for economic growth

C1. Therefore, climate change is the result of bad choices based on bad values that we should regret. (This often takes the form of a quasi-religious sense of ‘original sin’ among the climate woke)

C2. Therefore, we should prevent such mistakes from happening again (This further anti-technology/anti-growth conclusion is not drawn by everyone, but is powerful within the environmentalist movement)

Let me take each conclusion in turn. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. This Moment … late June 2022.

Sughra Raza. This Moment … late June 2022.

Digital photograph.

Hypomania

by Michael Abraham

I have been told it is a bad thing. I have been told this by doctors and friends and my parents and lovers. They worry over me, worry over me the way a Catholic worries over her rosary. They insist on the medication and the therapy and anything but this feeling, anything but this feeling you relish so intensely.

O, but to live without it is a waste, a wasteland, and not in the TS Eliot way: not a wasteland overbrimming with meaning, but a wasteland devoid of even the potential for meaning. Hypomania is summer thunder, is getting crushed by the rain. It is having sex with two men in one night, and learning their names, and learning their deepest fears because one is so open that deep fears tumble out. It is falling into Triangle Park, into the puff-puff warm feeling. It is taking ecstasy on the tongue and dancing all the night long. It is spending all your money and calling it good, for a good night out is only the sign of one who hopes. O, it is sex and drugs and money, but it is more than that, so much more than that. It is a deep thrum like a drum struck at the center of the being, an immaculate sound that emanates through the vibration of the whole body. It is an easy slide into Exactly Who He Wants To Be. The world is an oyster, and hypomania is the pearl: it is gorgeous; it is extravagant; it deserves to be worn at the neck as a sign of glamour and appeal. For one who has experienced it, there is nothing quite as quick as the slice of its blade upon the throat. It bleeds one out. It makes from one who is merely body, merely mind, something spectacular: a fountain of bright red conundrum, a spill of the holy stuff onto the ground. There is no living without it once you’ve had it. It is the best drug on the street. It is top-shelf liquor. It leaves nothing in its wake but wanting for it. Staying up to write all night, sweating profusely as you dance your aches out alone in front of the DJ booth, falling into the arms of any boy, falling into your own embrace, embracing yourself as a broken thing full of yearning: it is a true human condition. It is maybe the human condition laid bare. There is no proper way to say it, but to say that all the stars align for a moment, and in that moment, you are immortal; you are the absolute apotheosis of chance and luck. You take the world in your hands, and then you take the succor of the world in your mouth, and then you fill yourself until your greed for all the world has to offer is finally satiated. O, but it is never satiated!—not until the hypomania passes, and you pass with it, into the doldrums, into the never-ending blue of regret and depressive reconstruction of the self. You lose your ground in the hypomania, and then, in the depression, you get your ground back. And your ground is such a burden. To be free of oneself, to be an onslaught, to be a trick in the back pocket of a satyr prancing wild to a Madonna song: it is so very difficult to leave it. Read more »

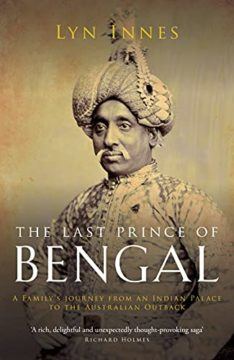

Princely State to Postcoloniality

by Claire Chambers

I know Lyn Innes from her career as an eminent postcolonial critic at the University of Kent. Since retirement, Innes has turned her hand to life writing. This is unsurprising when one learns of her unique and fascinating family history.

I know Lyn Innes from her career as an eminent postcolonial critic at the University of Kent. Since retirement, Innes has turned her hand to life writing. This is unsurprising when one learns of her unique and fascinating family history.

Her book The Last Prince of Bengal: A Family’s Journey from an Indian Palace to the Australian Outback is a story of two marriages and two British colonies, India and Australia.

Innes’ great-grandfather Mansour Ali Khan (1830–1884) was the final Nawab of Bengal, eighth in succession to Mir Jafar (1691–1765). As is well known, Mir Jafar collaborated with the British East India Company. His payment was to become the Nawab of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa: the greater part of eastern India. The East India Company also bestowed on Mir Jafar honour and rights, including a large pension or stipend. In return, the Company got freedom to tax the region, which they did with gusto.

Given that Innes is a respected postcolonialist, I was interested in her reaction to the lineage from Mir Jafar, widely regarded in India as a traitor. Furthermore, Mansour Ali Khan and other family members supported the British in the so-called Mutiny of 1857. After this Rebellion, the Governor-General of India was appointed by the British Parliament instead of the East India Company. Many members of Innes’ family were not nationalists and opposed Indian independence. However, it is clear from her dispassionate and rigorous account in this book that Innes is no royalist and that she is neither proud nor ashamed of her ancestors. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Does Respect for Legal Institutions Ultimately Serve Despots?

by Joseph Shieber

More than any other, one article I read last Friday, June 24, brought home to me how difficult it is to maintain respect for the law in the face of injustice.

You’re probably thinking that it was one of the articles reporting on the United States Supreme Court’s having struck down the 50 year old precedent in Roe v Wade, constitutionally guaranteeing to women in the United States the right to exercise control over their own bodies. It wasn’t.

Rather, it was an article in the South China Morning Post announcing the death, on Friday in Beijing, of the lawyer Zhang Sizhi at the age of 94.

Zhang, known as the “conscience of the lawyers” in China, was born in Henan province in 1927. After serving for three years in the Chinese Expeditionary Force, Zhang began studying law in 1947, graduating from the Renmin University of China in 1950. Zhang was only able to handle a few cases in the 1950s before being thrown into a reeducation camp as a “rightist” and intellectual. He spent 15 years in prison.

After his release, Zhang resumed his legal practice and began a career as a defender of the developing Chinese rule of law – and the principle of the freedom to dissent – that spanned over thirty years, from the 1980s to the 2010s. Read more »

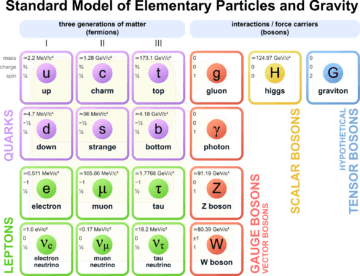

The Ur-Alternative: Quantum Mechanics As A Theory Of Everything

by Jochen Szangolies

At the close of the 20th century, the logical end-point of physics seemed clear: unify all physical phenomena under the umbrella of a single, unique ‘Theory of Everything’ (ToE). Indeed, many were convinced that this goal was well within reach: in his 1980 inaugural lecture Is the end in sight for theoretical physics?, Stephen Hawking, the physicist perhaps most closely associated with the quest for the ToE in the public eye, speculated that this journey might be completed before the turn of the millennium.

More than twenty years after, a ToE has not manifested—and moreover, seems in some ways more distant than ever. Confidence in the erstwhile ‘only game in town’, string/M-theory, has been waning in the face of floundering attempts to make contact with the real world. Without much hope of guidance from experiment, some have even been questioning whether the theory is ‘proper science’ at all—or, conversely, whether it requires a reworking of scientific methodology towards a ‘post-empirical’ framework from the ground up. But in the wake of string theory’s troubles, no other contender has risen up to take center stage. Read more »

Monday Photo

The Buried Giant, Memory, and the Past

by Derek Neal

In last month’s column, I wrote about the opening pages of Philip Roth’s Nemesis, and how Roth creates the backdrop of 1940’s Newark upon which the events of the novel play out. I’m using the words “backdrop” and “play out” intentionally, as these pages really do function as a sort of stage set that provides the context for the story which follows. This kind of storytelling is, I suppose, somewhat traditional or old fashioned. What it suggests is that the characters are products of their environment, and it’s important to explain the context in which they exist if the characters are to be understood. The setting of the story can also be seen as its own character, such that we must have a grasp of 1940’s Newark to comprehend the protagonist of the story, Bucky Cantor, because his understanding of the world and how he moves through it, his hopes, his dreams, and his fears, have been shaped, or to use a stronger word, created, by the fact of being born and growing up in Newark, New Jersey in the middle of the first half of the 20th century.

This may seem obvious, but in foregrounding the setting of the story, it also goes against the idea that people are unique, ahistorical individuals, which seems to be an increasingly common contemporary assumption. Nemesis makes this point explicit by placing the narrator in the present, or at least in the future in terms of the events of the story, and then having him relate what has taken place in the past. This is an acknowledgement that to attempt to tell a story about a certain time period from within that time period would in some ways be deceitful and anachronistic, running the risk of assuming that people in past times thought about themselves and the world in the same way that we do, or mapping a contemporary morality onto the past. Because it would be nearly impossible to faithfully recreate a past consciousness (although this is what any story about the past attempts to do), the practical solution is to frame the story from the viewpoint of a narrator in the present and admit defeat from the outset. This serves the purpose of recognizing the futility of the attempt while still trying to achieve the goal of fully recreating a different time and place. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 50

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Some years after Carlos died, another friend and another noted development economist, Hans Binswanger, was diagnosed as HIV-positive. He initially took that as a death sentence and gave away much of the material things he had. But by then the new antiretroviral drugs were in use, and possibly because of them lived an active life for another quarter century, until he died in Pretoria, South Africa in 2017 at age 74. In 2002, shortly before he left his World Bank job, he founded and endowed an NGO in Zimbabwe, that supported about 100 mostly HIV-positive children and their families by providing education, supplemental health care, and counseling. In South Africa he married his boyfriend Victor in a traditional multi-day Zulu celebration. Since then he has always identified his last name as Binswanger-Mkhize.

Some years after Carlos died, another friend and another noted development economist, Hans Binswanger, was diagnosed as HIV-positive. He initially took that as a death sentence and gave away much of the material things he had. But by then the new antiretroviral drugs were in use, and possibly because of them lived an active life for another quarter century, until he died in Pretoria, South Africa in 2017 at age 74. In 2002, shortly before he left his World Bank job, he founded and endowed an NGO in Zimbabwe, that supported about 100 mostly HIV-positive children and their families by providing education, supplemental health care, and counseling. In South Africa he married his boyfriend Victor in a traditional multi-day Zulu celebration. Since then he has always identified his last name as Binswanger-Mkhize.

Hans was born in Switzerland in a prominent Swiss family. He was a major agricultural economist with pioneering work on peasants’ behavior in the face of risk. This work was based on experiments carried out in India. I think I met him first in Hyderabad at ICRISAT, the International Crop Research Institute for Semi-Arid Tropics, where he was the principal economist for 5 years, before joining the World Bank.

In 1977 he invited me and Kalpana to present papers at a conference in Hyderabad on the subject of rural labor markets (later he co-edited a book where these papers were published). I remember the lavish party he gave for all the conference participants at his home which was a stunning converted-fortress in Hyderabad. The intensive ICRISAT village studies that started under his leadership in India made possible data-intensive work by many agriculture researchers all over the world, and generated over the years hundreds of Ph. D’s. Since then I have interacted with him many times, particularly when he was doing some policy work for the World Bank on land reform in South Africa. He came to Berkeley and addressed my graduate seminar on Economic Development. I last saw him at a meeting in Delhi, just a couple of years or so before his death. Read more »

The Federal Reserve says its remedies for inflation ‘will cause pain’, but to whom?

Clara Mattei in The Guardian:

The Fed’s recipe to bring prices under control will increase the cost of borrowing money, which is good news for creditors, while heavily indebted households that rely on loans for their daily survival will face higher bills.

The Fed’s recipe to bring prices under control will increase the cost of borrowing money, which is good news for creditors, while heavily indebted households that rely on loans for their daily survival will face higher bills.

The cost of borrowing will also increase government expenses for public works and social services, forcing states to further cut their budget, hurting the most precarious parts of society that rely most on these services.

Most importantly, as Powell himself has acknowledged, lowering incentives for businesses to invest will produce unemployment.

What Powell does not say is that the “pain” for working-class Americans is not an accident or even an unintended consequence.

More here.