by Claire Chambers

I know Lyn Innes from her career as an eminent postcolonial critic at the University of Kent. Since retirement, Innes has turned her hand to life writing. This is unsurprising when one learns of her unique and fascinating family history.

I know Lyn Innes from her career as an eminent postcolonial critic at the University of Kent. Since retirement, Innes has turned her hand to life writing. This is unsurprising when one learns of her unique and fascinating family history.

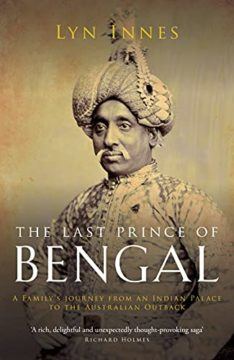

Her book The Last Prince of Bengal: A Family’s Journey from an Indian Palace to the Australian Outback is a story of two marriages and two British colonies, India and Australia.

Innes’ great-grandfather Mansour Ali Khan (1830–1884) was the final Nawab of Bengal, eighth in succession to Mir Jafar (1691–1765). As is well known, Mir Jafar collaborated with the British East India Company. His payment was to become the Nawab of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa: the greater part of eastern India. The East India Company also bestowed on Mir Jafar honour and rights, including a large pension or stipend. In return, the Company got freedom to tax the region, which they did with gusto.

Given that Innes is a respected postcolonialist, I was interested in her reaction to the lineage from Mir Jafar, widely regarded in India as a traitor. Furthermore, Mansour Ali Khan and other family members supported the British in the so-called Mutiny of 1857. After this Rebellion, the Governor-General of India was appointed by the British Parliament instead of the East India Company. Many members of Innes’ family were not nationalists and opposed Indian independence. However, it is clear from her dispassionate and rigorous account in this book that Innes is no royalist and that she is neither proud nor ashamed of her ancestors.

The family were Iraqi Shias, Mir Jafar being originally from Iraq. When Mansour Ali Khan lay dying of a stroke, he expressed a wish to be buried in Karbala, the sacred city of Shiism. The British were more prejudiced towards Shias than Sunnis. Perhaps this is because Tipu Sultan (1751–1799), seen as Britons’ most feared and dangerous enemy, had formed alliances with and protected a large group of Shias is south India’s Mysore region. Furthermore, the Bengal’s neighbouring province of Oudh (today known as Awadh) was governed by a Shia Nawab, Nasir-ud-Din Haidar Shah (1803–1837). This Nawab was regarded by the British as a ruler who had mishandled government. He convened an impressive court at Lucknow, replete with musicians and poets. The British interpreted this cultural centre as decadent, stigmatizing Shias as voluptuary and difficult to control.

Mansour Ali Khan was just eight years old when he came to Murshidabad’s throne. This was in 1838, just a couple of months after Queen Victoria had herself been crowned. Murshidabad in Bengal had originally been the capital of India. Under the Nawabs it was an opulent and attractive city. When Clive of India went there in 1757, he wrote in amazement that it was more beautiful and desirable than London, and that Murshidabadis were wealthier than Londoners. During the course of her research, Innes visited the city several times. She found it small, dusty, and derelict. Her great-grandfather’s palace, built in 1828 in a European style and resembling Calcutta’s Government House or London’s National Art Gallery, is now preserved as the state museum. Other oriental-style palaces stand dilapidated. When the East India Company decided to move its headquarters to Calcutta, then the trade and wealth of Murshidabad shifted with the Company to Calcutta.

Bengal had originally been the capital of India. Under the Nawabs it was an opulent and attractive city. When Clive of India went there in 1757, he wrote in amazement that it was more beautiful and desirable than London, and that Murshidabadis were wealthier than Londoners. During the course of her research, Innes visited the city several times. She found it small, dusty, and derelict. Her great-grandfather’s palace, built in 1828 in a European style and resembling Calcutta’s Government House or London’s National Art Gallery, is now preserved as the state museum. Other oriental-style palaces stand dilapidated. When the East India Company decided to move its headquarters to Calcutta, then the trade and wealth of Murshidabad shifted with the Company to Calcutta.

The young Nawab was given a very British education. He was supervised closely by British agents. This succession of men became his de facto Regents, controlling his money, moving him away from his mother’s quarters and discouraging too close an association with his Muslim tutors. The book has much to say about the changing nature of colonialism, the prince’s chequered relationships with various British colonial officials, and the financial mismanagement (read: robbery) that abounded.

Until around the time of Mansour Ali Khan’s accession as Nawab in 1838, the court language had been Persian. In 1835 Thomas Babington Macaulay’s ‘Minute on Education’ chauvinistically advocated that English become India’s courtly, legal, and educational language. Mansour Ali Khan was forced to learn English. He protested because his ancestors has not known the language. As a powerless boy, though, he had little choice but to become proficient in English as well as Persian.

When Mansour Ali Khan was sixteen, the latest British agent, Henry Whitelock Torrens, was responsible for stealing a great deal of his fortune. Torrens persuaded the young Nawab to invest approximately two million rupees in a company the Briton recommended. When Torrens died six years later, it was found that he had taken this money for himself. A great many of the princely state’s jewels had also been spirited to Torrens’ mistress, a British actress in Calcutta.

Subsequent agents were rude and racist, writing extraordinarily vituperative letters to this young man, who was essentially the king of Bengal. The Nawab resented his treatment and the ways in which the British had scaled down or outright denied the promises given to his forebears. Finally, in 1869, he decided to come to Britain and petition Queen Victoria for a return of his money, rights, and status.

While he was in England, he stayed in a grand hotel where he met a sixteen-year-old chambermaid from east London. Her name was Sarah Vennell, and she was Innes’ great-grandmother. Sarah came from a poor family in London’s East End. With her six siblings, she lived on the same street in which Charlie Chaplin would reside about three decades later.

When Sarah was growing up in the late 1850s and early 1860s, one opportunity for women was to work as domestic servants. A small step up from that was to work in hotels. Sarah probably felt she had done extremely well by getting a job in Knightsbridge’s Alexandra Hotel, which was frequented by such luminaries as the Rothschilds and the Sultan of Zanzibar.

When Sarah was growing up in the late 1850s and early 1860s, one opportunity for women was to work as domestic servants. A small step up from that was to work in hotels. Sarah probably felt she had done extremely well by getting a job in Knightsbridge’s Alexandra Hotel, which was frequented by such luminaries as the Rothschilds and the Sultan of Zanzibar.

This was where the Nawab spied the attractive teenager. According to family lore, Sarah insisted on marriage, refusing to be his mistress. They therefore had a proper Muslim nikah, Sarah becoming Mansour Ali Khan’s fourth wife. She took the name Nawab Sarah Begum and was proud of her title. The couple lived together in London for ten years and had six children, four of whom survived.

However, Sarah’s Cinderella story of a rags to riches journey from chambermaid to princess went sour, ending in divorce and legal wrangling. After their decade-long marriage, the Nawab took up with another maid, Julia Lewis. She became Mansour Ali Khan’s temporary (mutah) wife. This meant the Nawab was responsible for Julia and her children. However, he could not legally marry a fifth wife. Estranged from Sarah, the Nawab went back to India with their four surviving children.

This left Sarah to sue for custody from England. At the time, if a marriage was illegitimate the woman would assume full custody, leaving the father with no rights to his children. To get her children back, Sarah decided to claim that the marriage was illegitimate. That was a weighty decision. It signalled she was not a respectable woman, and meant she could not claim the pension to which as the wife of a Nawab she was entitled. In any case, the courts adjudicated against her. They judged that the marriage wasn’t illegitimate and that the father’s parenthood had to be respected.

In the end, Sarah only got her two boys back. Their oldest children, daughters named Miriam and Vaheedoonissa, had been taken to India in 1880 where they remained for the rest of their lives. When the Nawab died in 1884, Sarah tried to get custody over the girls by averring through her lawyers that they were in danger of being sold into marriage, becoming child brides against their will. In fact, they never married. The older one, Miriam, was offered a suitor, whom she refused. Both sisters expressed the desire not to marry, and their wishes were respected. Innes’ understanding is that they chose not to return to England. This, she thinks, was partly because they were cherished by their grandmother in India, had become Urdu- rather than English-speaking, and had begun to identify as Indian.

When she was a teenager, Innes’ great-aunt Vaheedoonissa began to write to her from India. She didn’t write in English, but wrote or dictated her letters in Urdu, and then a scribe translated them. Along with her words she sent parcels of perfumes and scarves from Murshidabad. She would comment on the news, as for instance when Innes’ mother’s cousin Iskander Mirza became President of Pakistan in 1956. For Innes, those letters were a wonderful window on a world and a worldview very different to her own remote farm in Australia.

them. Along with her words she sent parcels of perfumes and scarves from Murshidabad. She would comment on the news, as for instance when Innes’ mother’s cousin Iskander Mirza became President of Pakistan in 1956. For Innes, those letters were a wonderful window on a world and a worldview very different to her own remote farm in Australia.

The boys might have stayed in India too and acclimatized like their sisters. However, the Nawab’s express wish was that, unlike the daughters, they should be sent back to England for an education. The younger of these, whose name was Nusrat Ali Mirza, was Innes’ grandfather.

In his forties, Nusrat decided to emigrate to Australia, because he found having the title of Indian prince made it impossible for him to survive and thrive in England. He wanted his offspring to grow up as ordinary children elsewhere, and so he chose anonymity in Australia.

From 1901 to 1973 Australia implemented what became known as the White Australia policy. Immigrants who were not of European heritage were unable to stay in the nation-state. In order to emigrate to Australia, Innes’ grandfather had to change his name from Nusrat Ali Mirza to Norman Alan Mostyn.

Nusrat kept quiet about his Asian background. Yet when Innes started school at the age of ten, her classmates bullied her, calling her grandparents a Black prince and Black princess. This came despite the fact that her grandmother was white English and her grandfather was light-complexioned with blue eyes. As children, Innes and her siblings were discouraged from talking about their background because of Australian immigration laws and the extent and severity of racism in the country. It was only when Innes went to America and began to teach at the Tuskegee Institute, a traditionally Black college, that she became interested in the absurdity of racial classifications. Indeed, she positions an epigraph from Jean Genet at the book’s beginning, ‘But what is a black person then? And first of all, what colour is he?’

This book contains rich material on gender. Not only is there discussion of the obvious roles for women in this period, as mothers, daughters, and wives, but we are also given glimpses of courtesans, mistresses, governesses, chambermaids, and temporary wives. There is intersectionality in the story of Sarah’s sexuality; her eagerness to be seen as a respectable woman; the issue of social class, given the poverty of both Sarah’s and Julia’s childhoods; as well as the racial dimension pertaining to the Nawab’s Indian identity.

This book contains rich material on gender. Not only is there discussion of the obvious roles for women in this period, as mothers, daughters, and wives, but we are also given glimpses of courtesans, mistresses, governesses, chambermaids, and temporary wives. There is intersectionality in the story of Sarah’s sexuality; her eagerness to be seen as a respectable woman; the issue of social class, given the poverty of both Sarah’s and Julia’s childhoods; as well as the racial dimension pertaining to the Nawab’s Indian identity.

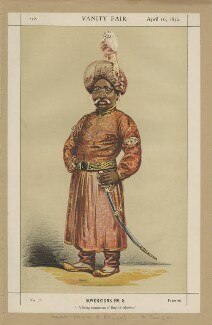

In nineteenth-century Britain, according to Innes, the identity component that seemed to trump all others was class. The Nawab was a favourite of Queen Victoria’s, who was regularly invited to court receptions and aristocratic soirees. He was in the papers almost every day, as one of the era’s most prominent figures. Sarah was never mentioned. As the wife of a Muslim Nawab, she was not expected to accompany her husband to society events. More than that, her class mattered to the British, and so she was never his partner at social engagements. Ironically, some time after the Nawab’s death, Sarah started to come into her own and lead an independent life with a relatively high status.

There are no public photographs of any the family’s women. Meanwhile there are hundreds of pictures of the Nawab, his son Nusrat Ali Mirza, and other men from the dynasty.

Yet with this book, Innes sketches a vivid portrait of her male and female ancestors, the rich and the poor.