Month: May 2022

Tom Jobim – As melhores

Jennifer Egan’s worldwide webs

Erin Somers in The Nation:

In Jennifer Egan’s 2011 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel A Visit From the Goon Squad, “time is a goon.” It is time that steals youthful promise and dashes hopes. Time that makes people unrecognizable to themselves. In it, time derails the life of kleptomaniac Sasha Blake; it disillusions her record producer boss, Bennie Salazar, and diminishes record executive Lou, once so vital to his teenage girlfriend Jocelyn. Music is good, we are told.

In Jennifer Egan’s 2011 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel A Visit From the Goon Squad, “time is a goon.” It is time that steals youthful promise and dashes hopes. Time that makes people unrecognizable to themselves. In it, time derails the life of kleptomaniac Sasha Blake; it disillusions her record producer boss, Bennie Salazar, and diminishes record executive Lou, once so vital to his teenage girlfriend Jocelyn. Music is good, we are told.

Authenticity is redemptive. But time causes us to stray from these ideals. By the end of the novel, we find ourselves in a world where babies have smartphones and the sun sets in the mid-afternoon because of “warming-related ‘adjustments’ to the Earth’s orbit.”

In her new “sibling” novel, The Candy House, time’s passage is a foregone conclusion. We meet many of the same characters: Sasha, who has channeled her impulse for petty theft into creating sculptures out of trash; Lou, who remains disgusting. But now the real problem is the Internet.

More here.

Considering The Intersections Of Literature And Science

Carlo Rovelli at Lit Hub:

The greatness of literature lies in its capacity to communicate the experiences and feelings of human beings in all their variety, affording us glimpses of the boundless vastness of humanity. Literature has told us about war, adventure, love, the monotony of everyday life, political intrigues, the life of different social classes, murderers, banal individuals, artists, ecstasy, the mysterious allure of the world. Can it also tell us anything about the real and profound emotions connected with great science?

The greatness of literature lies in its capacity to communicate the experiences and feelings of human beings in all their variety, affording us glimpses of the boundless vastness of humanity. Literature has told us about war, adventure, love, the monotony of everyday life, political intrigues, the life of different social classes, murderers, banal individuals, artists, ecstasy, the mysterious allure of the world. Can it also tell us anything about the real and profound emotions connected with great science?

Of course it can: literature is full of science. An entire genre, science fiction, is fed by it. Playwrights have engaged with it, not the least of them Brecht in his Galileo, a play that goes to the heart of the critical attitude upon which scientific thought is based.

more here.

On Suzanne Valadon

Hannah Stamler at Artforum:

A SELF-PORTRAIT from 1911 shows Suzanne Valadon at work, presumably creating the image before us. Holding a paint-streaked palette, she turns slightly to the right with lips pursed and eyes narrowed, likely scrutinizing her reflection in a mirror beyond the frame. When Valadon made the portrait, at age forty-six, she would have been quite accustomed to holding a pose. Raised by a single mother in Montmartre, heady epicenter of the Parisian avant-garde, she began working as an artist’s model at the age of fifteen, sitting for the likes of Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, her friend and lover, who nicknamed her “Suzanna” (her real name was Marie-Clémentine) in winking reference to the biblical figure whose beauty tormented older men. Less familiar to the middle-aged Valadon was holding a brush. The self-taught artist didn’t seriously develop her practice until she was in her thirties, when marriage to a wealthy businessman afforded her the necessary time and support; she only began working with oil paints in 1909, the same year she left her conjugal home to take up with André Utter, a friend of her son, Maurice Utrillo, and more than twenty years her junior. Forged in a moment of personal and professional renewal, Self-Portrait declares Valadon’s hard-won status as subject and painter, mistress of her own canvas double. Valadon spent more than a decade watching male artists assess her and pick her apart; now behind the easel, she contemplates herself with shrewd determination.

A SELF-PORTRAIT from 1911 shows Suzanne Valadon at work, presumably creating the image before us. Holding a paint-streaked palette, she turns slightly to the right with lips pursed and eyes narrowed, likely scrutinizing her reflection in a mirror beyond the frame. When Valadon made the portrait, at age forty-six, she would have been quite accustomed to holding a pose. Raised by a single mother in Montmartre, heady epicenter of the Parisian avant-garde, she began working as an artist’s model at the age of fifteen, sitting for the likes of Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, her friend and lover, who nicknamed her “Suzanna” (her real name was Marie-Clémentine) in winking reference to the biblical figure whose beauty tormented older men. Less familiar to the middle-aged Valadon was holding a brush. The self-taught artist didn’t seriously develop her practice until she was in her thirties, when marriage to a wealthy businessman afforded her the necessary time and support; she only began working with oil paints in 1909, the same year she left her conjugal home to take up with André Utter, a friend of her son, Maurice Utrillo, and more than twenty years her junior. Forged in a moment of personal and professional renewal, Self-Portrait declares Valadon’s hard-won status as subject and painter, mistress of her own canvas double. Valadon spent more than a decade watching male artists assess her and pick her apart; now behind the easel, she contemplates herself with shrewd determination.

more here.

Are COVID surges becoming more predictable?

Ewen Callaway in Nature:

Here we go again. Nearly six months after researchers in South Africa identified the Omicron coronavirus variant, two offshoots of the game-changing lineage are once again driving a surge in COVID-19 cases there.

Here we go again. Nearly six months after researchers in South Africa identified the Omicron coronavirus variant, two offshoots of the game-changing lineage are once again driving a surge in COVID-19 cases there.

Several studies released in the past week show that the variants — known as BA.4 and BA.5 — are slightly more transmissible than earlier forms of Omicron1, and can dodge some of the immune protection conferred by previous infection and vaccination2,3.

“We’re definitely entering a resurgence in South Africa, and it seems to be driven entirely by BA.4 and BA.5,” says Penny Moore, a virologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, whose team is studying the variants. “We’re seeing crazy numbers of infections. Just within my lab, I have six people off sick.”

However, scientists say it is not yet clear whether BA.4 and BA.5 will cause much of a spike in hospitalizations in South Africa or elsewhere.

More here.

NATO’s philosophers

Santiago Zabala and Claudio Gallo at Aljazeera:

In a recent article – Putin’s philosophers: Who inspired him to invade Ukraine? – we outlined the theoretical stances of three thinkers who likely helped build the geopolitical vision of the Russian president and inspired his ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Indeed, there are many ways in which the views and works of Vladislav Surkov, Ivan Ilyin, and Alexandr Dugin can help us understand the idea of Russian exceptionalism and the ideology that drives Putin.

In a recent article – Putin’s philosophers: Who inspired him to invade Ukraine? – we outlined the theoretical stances of three thinkers who likely helped build the geopolitical vision of the Russian president and inspired his ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Indeed, there are many ways in which the views and works of Vladislav Surkov, Ivan Ilyin, and Alexandr Dugin can help us understand the idea of Russian exceptionalism and the ideology that drives Putin.

But looking only at the thinkers who inspired Putin is, of course, not enough to understand the devastating war in Ukraine in all its complexity. The Russian leader, after all, says he felt compelled to invade the country in late February due to the North Atlantic Alliance’s (NATO) ongoing expansion towards his country’s borders. So what, or who, inspired NATO to act this way? Which thinkers were behind the NATO strategies that paved the way for a conflict that has killed thousands of people, displaced millions, and raised the possibility of nuclear war?

More here.

Nobel Laureate John C. Mather: How the James Webb Space Telescope will unfold the universe

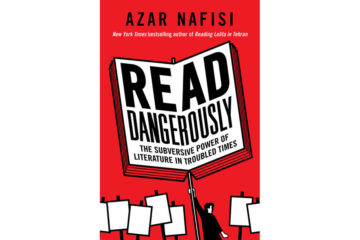

Not meant to soothe: How the truths of fiction can challenge and stir

Terry Hartle in The Christian Science Monitor:

Azar Nafisi burst on the literary scene with “Reading Lolita in Tehran,” which recounted her efforts to teach Western literature to a small group of young women in Iran. A risky and challenging undertaking in that totalitarian state, but one that underscored, once again, the power of books to transform lives. In “Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times,” she once again writes about the power of the written word to shape the way we see the world – this time by focusing on the present moment.

Azar Nafisi burst on the literary scene with “Reading Lolita in Tehran,” which recounted her efforts to teach Western literature to a small group of young women in Iran. A risky and challenging undertaking in that totalitarian state, but one that underscored, once again, the power of books to transform lives. In “Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times,” she once again writes about the power of the written word to shape the way we see the world – this time by focusing on the present moment.

Nafisi was born in Tehran, Iran, to open-minded and politically active parents. Her father served as mayor of Tehran for two years but was jailed for political reasons. Before his four-year imprisonment, he instilled in his daughter an abiding love of literature and stories. She was educated abroad, eventually earning a Ph.D. in English literature in the United States. Nafisi returned to Iran and taught there for 18 years before she was expelled from the university for failing to wear a veil. Eventually, she moved to America and became a citizen.

Through it all, she writes, “books and stories have been my talismans, my portable home, the only home I could rely on, the only home I knew would never betray me, the only home I could never be forced to leave. Reading and writing have protected me through the worst moments of my life, through loneliness, terror, doubt, and anxiety.”

How 400,000 People Landed Apollo 11 on the Moon

Catherine Thimmesh in Delancey Place:

“Their voices were rapid-fire. Crisp. Assured. There was no hesitation. But you could practically hear the adrenaline rushing in their vocal tones, practically hear the thumping of their hearts as the alarms continued to pop up.

“Their voices were rapid-fire. Crisp. Assured. There was no hesitation. But you could practically hear the adrenaline rushing in their vocal tones, practically hear the thumping of their hearts as the alarms continued to pop up.

“Then the Eagle was down to 2,000 feet. Another alarm! 1202. Mission Control snapped, Roger, no sweat. And again, 1202! Then the Eagle was down to 700 feet, then 500. Now, they were hovering — helicopter-like — presumably scouting a landing spot.

“In hundreds of practice simulations, they would have landed by now. But Mission Control couldn’t see the perilous crater and boulder field confronting Neil and Buzz. Those things, coupled with the distraction of the alarms, had slowed them down.

“More than eleven minutes had passed since they started down to the moon. There was only twelve minutes’ worth of fuel in the descent stage.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Rearview Mirror

This little pond in the air is

not a spring but sink into which

trees and highway, bank and fields are

sipped away to minuteness. All

split on the present then merge in

stretched perspective, radiant in

reverse, the wide world guttering

back to one lit point, as our way

sweeps away to the horizon

in this eye where the past flies ahead.

by Robert Morgan

from The Language They Speak Is Things to Eat

University of North Carolina Press, 1994

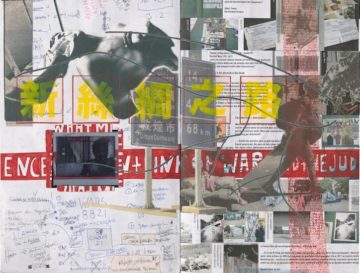

War by Another Name: Sanctions are not a gentler alternative to conflict

Joshua Craze in The Baffler, with photographic collages by Wolf Böwig:

The use of sanctions doubled in the decade following 2000, while their rate of success plummeted. The Global Sanctions Database evaluates that from 1985 to 2000, they worked between 25 and 40 percent of the time; by 2016, that figure had fallen to below 20 percent. Why, then, do sanctions remain an instrument of first resort for the American foreign policy establishment? Their centrality is paradoxically a sign of American weakness. In an increasingly multipolar world, the United States has fewer ways of influencing global politics and less domestic appetite to do so. Sanctions are one of the last tools in an emptying diplomatic toolbox, as illustrated by recent events in Afghanistan and Russia.

The use of sanctions doubled in the decade following 2000, while their rate of success plummeted. The Global Sanctions Database evaluates that from 1985 to 2000, they worked between 25 and 40 percent of the time; by 2016, that figure had fallen to below 20 percent. Why, then, do sanctions remain an instrument of first resort for the American foreign policy establishment? Their centrality is paradoxically a sign of American weakness. In an increasingly multipolar world, the United States has fewer ways of influencing global politics and less domestic appetite to do so. Sanctions are one of the last tools in an emptying diplomatic toolbox, as illustrated by recent events in Afghanistan and Russia.

In August 2021, the United States impounded $9.4 billion of Afghan Central Bank assets, following its humiliating withdrawal from Kabul. The consequences for Afghanistan are sure to be grim. On March 25, 2022, the World Food Program predicted that 22.8 million people—more than half of the country’s population—will be acutely food insecure this year, with 8.7 million facing famine-like conditions. Biden has promised to increase food aid, but, as a group of forty-eight Democratic members of Congress noted in December 2021, “No increase in food and medical aid can compensate for the macroeconomic harm of soaring prices of basic commodities, a banking collapse, a balance-of-payments crisis, a freeze on civil servants’ salaries, and other severe consequences that are rippling throughout Afghan society, harming the most vulnerable.”

Planning for sanctions against Russia began in November 2021, when U.S. intelligence received credible reports about the invasion of Ukraine.

More here.

Climate crisis: what lessons can we learn from the last great cooling-off period?

Michael Marshall in The Guardian:

In early February 1814, an elephant walked across the surface of the Thames near Blackfriars Bridge in London. The stunt was performed during the frost fair, when temperatures were so cold that for four days the top layers of the river froze solid. Londoners promptly held a festival, complete with what we might now call pop-up shops and a lot of unlicensed alcohol.

In early February 1814, an elephant walked across the surface of the Thames near Blackfriars Bridge in London. The stunt was performed during the frost fair, when temperatures were so cold that for four days the top layers of the river froze solid. Londoners promptly held a festival, complete with what we might now call pop-up shops and a lot of unlicensed alcohol.

Nobody could have known it at the time, but this was the last of the Thames frost fairs. They had taken place every few decades, at wildly irregular intervals, for several centuries. One of the most celebrated fairs took place during the Great Frost of 1683-84 and saw the birth of Chipperfield’s Circus. But the river in central London has not frozen over since 1814.

The frost fairs are perhaps the most emblematic consequences of the “little ice age”, a period of chilly weather that lasted for several centuries. But while Londoners partied on the ice, other communities faced crop failures and other threats. The story of the little ice age is one of societies forced to adapt to changing conditions or perish.

It’s also a long-standing mystery. Why did the climate cool and why did it stay that way for centuries?

More here.

What Does Physics Tell Us About Consciousness?

Political deadlock: President, Parliament and protesters

Ram Manikkalingam in the Sunday Times:

Sri Lanka is at a political deadlock. Protesters want the President and parliamentarians to go home. Parliament wants the President to go home. And the President wants the protesters to go home. But no one is going home. Meanwhile, we cannot change the President without changing the prime minister. We cannot change the prime minister because no party leader wants to be saddled with the economic crisis. And we cannot manage the economic crisis because there is no new prime minister. How do we get out of this triple deadlock?

Sri Lanka is at a political deadlock. Protesters want the President and parliamentarians to go home. Parliament wants the President to go home. And the President wants the protesters to go home. But no one is going home. Meanwhile, we cannot change the President without changing the prime minister. We cannot change the prime minister because no party leader wants to be saddled with the economic crisis. And we cannot manage the economic crisis because there is no new prime minister. How do we get out of this triple deadlock?

It is very hard for the protesters to shift tack, because there are many tens of thousands. It is difficult for parliament to move, because at least 113, out of the 225 members, must agree. But it is easier for the President to change course because he can take a decision and implement it on his own. So what can he do that meets the concerns of the protesters?

The President can declare that he is ready to get rid of the executive presidency. He can commit to initiating a process of constitutional change within parliament to do that. He can also commit not to serve out his term, but to quit as soon as the amendment is passed.

More here.

The Pop Song That’s Uniting India and Pakistan

Priyanka Mattoo at The New Yorker:

A few years ago, the musician Ali Sethi was driving through Punjab, behind a jingle truck—the long-haul trucks known in his native Pakistan for their filigreed paint designs—when he spotted a phrase in florid Punjabi calligraphy on its back. “Agg lavaan teriya majbooriya nu,” it said—a call to “set fire to your compulsions.” It’s not uncommon to glimpse bits of verse, or dire warnings—against straying eyes or losing yourself in the big world out there—among the fluorescent parrots and tropical fruit schemes of jingle trucks. But Sethi couldn’t stop thinking about that phrase.

A few years ago, the musician Ali Sethi was driving through Punjab, behind a jingle truck—the long-haul trucks known in his native Pakistan for their filigreed paint designs—when he spotted a phrase in florid Punjabi calligraphy on its back. “Agg lavaan teriya majbooriya nu,” it said—a call to “set fire to your compulsions.” It’s not uncommon to glimpse bits of verse, or dire warnings—against straying eyes or losing yourself in the big world out there—among the fluorescent parrots and tropical fruit schemes of jingle trucks. But Sethi couldn’t stop thinking about that phrase.

It inspired the first line of “Pasoori,” the thirty-seven-year-old’s latest single, a joyous, dance-fuelled hit that has drawn more than a hundred million views on YouTube since its release three months ago and is playing on the radio everywhere, from the United Arab Emirates to Canada. The song is stealthily subversive: a traditional raga—the classical Indian framework for musical improvisation—has been laid over an infectious beat that sounds South Asian, Middle Eastern, and, improbably, reggaetón, all at once.

more here.

Pasoori | Ali Sethi x Shae Gill

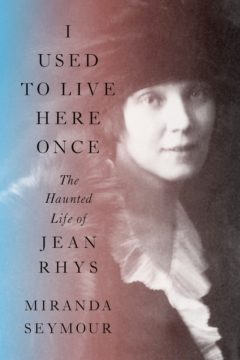

The Haunted Life of Jean Rhys

Claudia Fitzherbert at Literary Review:

In 1974, at the age of eighty-four, Jean Rhys was asked in a television interview whether she would prefer to write or be happy were she to live her life over again. ‘Oh, happiness!’ she replied without missing a beat.

In 1974, at the age of eighty-four, Jean Rhys was asked in a television interview whether she would prefer to write or be happy were she to live her life over again. ‘Oh, happiness!’ she replied without missing a beat.

Rhys had been channelling unhappiness since the publication of her first volume of short stories in 1927. The four novels she published before the war chart journeys that go from bad to worse for heroines who end up alone in dreary hotel rooms. Ford Madox Ford, her much older mentor and unfaithful lover, said she had a ‘terrific – an almost lurid! – passion for stating the case of the underdog’ as well as a ‘singular instinct for form’. The novels are spare, witty and completely unsentimental. Her protagonists sometimes dwell on who they were or might have been if their looks hadn’t faded or their lovers had been kinder or their babies hadn’t died. Their creator never falters in her acknowledgement that they are who they’ve become.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Customs

The second farthest place that I have been

from anything that you will ever know is

in love. Like this, I mean. Like how when

condors fledge, they leap from icy cliffs then

fly. They ask: Destination? Purpose? I say, Yes,

I wish to have one. Let’s say “South.” Ushuaia,

the land of lagooned mountains, turquoise in

the snow. Let’s say I have a backup answer, but

we will never hear it because I’ll go and I’ll be

gone, like how you went, too—became a time

lapse of the clouds over El Chaltén: just some slow

recording on my phone. That was supposed to be

the time of my life. That was supposed to be when

we got closer. What even is the word explore? Flamingoes

in their craning lines, pink perforations in the sky and salt. Ñandu.

Receding glaciers. Perhaps we should just accept climate change

as a liberation of the water. We’re its savior, returning it to

its rightful salten home. And who was Magellan,

anyway? There are penguins with his name, but

only in colonial tongues, and I call them that. And

you sent me here to learn what a disaster the world is—

has always been because of men like me. See it

all, you said; and I signed on without considering

the finest print: sure to witness disaster. We’ll be

fighting over love and water in our lifetimes.

We’ll squander them like years, but

faster. And even when we have

none left, we’ll still believe

we have the answers.

by Benjamin Faro

from The Echo Theo Review 2/11/22

The women who redefined colour

Kelly Grovier in BBC:

In 1805, a little-known English artist and amateur painting instructor did what no woman before her ever had: publish a book on the subject of colour theory. Though frustratingly few details of the life and career of Mary Gartside have survived, her unprecedented volume An Essay on Light and Shade, on Colours, and on Composition in General reveals evidence of extraordinary creative genius. Modestly introduced by its obscure author as little more than a guidebook to “the ladies I have been called upon to instruct in painting”, Gartside’s study is accompanied by a series of strikingly abstract images unlike any produced previously by a writer or artist of any gender.

At first glance, you could easily mistake Gartside’s eight watercolour “blots” for magnified floralscapes that anticipate the outsized stamens and pistils that the US artist Georgia O’Keeffe would begin exploding out of all proportion more than 100 years later. But look again at these lucent surges of almost petals, whose vibrancy of colour is unshackled to tangible shape, and any certainty you may have had about what it is that these images portray or what they mean begins to break down. Neither fragrant blossoms plucked from the real world nor imaginary blooms unfolding in the mind, Gartside’s abstract blots burst beyond the borders of themselves a full century before non-figurative painting established itself on the better-known canvases of Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian.

More here.