by Jonathan Kujawa

Bob Moses was a moral giant who worked tirelessly to fundamentally improve the world for others. He came from a low-income family but, through talent and hard work, earned a degree from Hamilton College and a master’s degree from Harvard in the philosophy of mathematics. He left graduate school for family reasons. To earn a living he began to teach mathematics at a private school in New York City. After a few years, Moses read of the people his age who were conducting sit-in protests against segregation in the South and knew he had to join the struggle.

Moses was viewed with some suspicion when he first arrived. He was an academically inclined, Harvard-educated philosopher who seemed out of place in the hot, dangerous climate of the civil rights South. Suspicions were only heightened when they heard he spent free time attending a mathematics lecture at Atlantic University on the “Ramifications of Gödel’s Theorem” [2]. Soon enough they discovered he was the real deal. Read more »

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021. If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

I knew that Cambridge was by the river Cam, but the first day when I looked for it I could not find it. From the map I knew that on my way to the Economics Department I had to cross it, I stopped and looked around but I could not see anything like a river. Then I asked a passerby, and he pointed to what I had thought was a small ditch or a canal. It was difficult to take it as a river, as in India I was used to much bigger rivers. Over time, however, I saw the serene beauty of this mini-river, with its placid water by the weeping willows, the swans, gliding boats and all.

I knew that Cambridge was by the river Cam, but the first day when I looked for it I could not find it. From the map I knew that on my way to the Economics Department I had to cross it, I stopped and looked around but I could not see anything like a river. Then I asked a passerby, and he pointed to what I had thought was a small ditch or a canal. It was difficult to take it as a river, as in India I was used to much bigger rivers. Over time, however, I saw the serene beauty of this mini-river, with its placid water by the weeping willows, the swans, gliding boats and all. Social media have gutted institutions: journalism, education, and increasingly the halls of government too. When Marjorie Taylor Greene displays some dumb-as-hell anti-communist Scooby-Doo meme before congress, blown up on poster-board and held by some hapless staffer, and declares “This meme is very real”, she is channeling words far, far wiser than the mind that produced them. We’re all just sharing memes now, and those of us who hope to succeed out there in “reality”, in congress and classrooms and so on, momentarily removed from our screens and feeds, must learn how to keep the memes going even then. “Real-world” events, in other words, are staged by the victors in our society principally with an eye to the potential virality of their online uptake. And when virality is the desired outcome, clicks effected in support or in disgust are all the same. Thus the naive idea that AOC wore her “Tax the Rich” gown to a particular event attended by a select crowd within a well-defined physical space completely distorts the motivation behind the gesture, which was, obviously, to make waves not during, but immediately after, the event, not for the people at the event, but for all the people who were not invited.

Social media have gutted institutions: journalism, education, and increasingly the halls of government too. When Marjorie Taylor Greene displays some dumb-as-hell anti-communist Scooby-Doo meme before congress, blown up on poster-board and held by some hapless staffer, and declares “This meme is very real”, she is channeling words far, far wiser than the mind that produced them. We’re all just sharing memes now, and those of us who hope to succeed out there in “reality”, in congress and classrooms and so on, momentarily removed from our screens and feeds, must learn how to keep the memes going even then. “Real-world” events, in other words, are staged by the victors in our society principally with an eye to the potential virality of their online uptake. And when virality is the desired outcome, clicks effected in support or in disgust are all the same. Thus the naive idea that AOC wore her “Tax the Rich” gown to a particular event attended by a select crowd within a well-defined physical space completely distorts the motivation behind the gesture, which was, obviously, to make waves not during, but immediately after, the event, not for the people at the event, but for all the people who were not invited. Topologists study the properties of general versions of shapes, called manifolds. Their animating goal is to classify them. In that effort, there are a few key distinctions. What exactly are manifolds, and what notion of sameness do we have in mind when we compare them?

Topologists study the properties of general versions of shapes, called manifolds. Their animating goal is to classify them. In that effort, there are a few key distinctions. What exactly are manifolds, and what notion of sameness do we have in mind when we compare them? There is great emotional weight in literature. Anyone who has cried for the death of Old Yeller, laughed at the antics of Lucky Jim, or been thrilled by the adventures of Simon Templar can attest to that simple fact. What has never been simple is understanding why a string of written words can create such an emotional response, or possibly more important, why some strings achieve it so much more effectively than others.

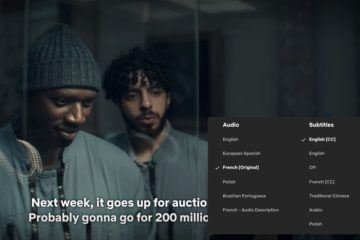

There is great emotional weight in literature. Anyone who has cried for the death of Old Yeller, laughed at the antics of Lucky Jim, or been thrilled by the adventures of Simon Templar can attest to that simple fact. What has never been simple is understanding why a string of written words can create such an emotional response, or possibly more important, why some strings achieve it so much more effectively than others. I’m an audiovisual translator, which means that I—and others like me—help you understand the languages spoken on screen: You just click that little speech bubble icon in the bottom-right corner of your preferred streaming service, select the subtitles or the dub, and away you go. These scripts are all written by someone like myself, sitting quietly at a computer and spending day after day trying to figure out, “What are they actually saying here?”

I’m an audiovisual translator, which means that I—and others like me—help you understand the languages spoken on screen: You just click that little speech bubble icon in the bottom-right corner of your preferred streaming service, select the subtitles or the dub, and away you go. These scripts are all written by someone like myself, sitting quietly at a computer and spending day after day trying to figure out, “What are they actually saying here?” H

H On the cover of her new album, Dar Williams stands on a floating platform in a lake. A breeze ripples the water so that it’s as wrinkled as elephant skin. As Ms. Williams gazes toward an unseen horizon, her scarlet shawl flutters behind her like a vapor trail. The atomistic image is metaphorical. Ms. Williams says the photo, taken by a drone, makes her look like a red dot destination marker on a map. The album, debuting Oct. 1, is titled “I’ll Meet You Here.” “Somehow we have to figure out how to continue to meet the moment and meet one another,” even when we seem to be stranded, explains the folk singer in a phone call.

On the cover of her new album, Dar Williams stands on a floating platform in a lake. A breeze ripples the water so that it’s as wrinkled as elephant skin. As Ms. Williams gazes toward an unseen horizon, her scarlet shawl flutters behind her like a vapor trail. The atomistic image is metaphorical. Ms. Williams says the photo, taken by a drone, makes her look like a red dot destination marker on a map. The album, debuting Oct. 1, is titled “I’ll Meet You Here.” “Somehow we have to figure out how to continue to meet the moment and meet one another,” even when we seem to be stranded, explains the folk singer in a phone call.