https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhH41BunZZM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhH41BunZZM

Nancy MacLean over at INET:

Nancy MacLean over at INET:

The year 2021 has proved a landmark for the “school choice” cause as Republican control of a majority of state legislatures combined with pandemic learning disruptions to set the stage for multiple victories. Seven U.S. states have created new “school choice” programs and eleven others have expanded current programs, with laws that authorize taxpayer-funded vouchers for private schooling, provide tax credits, and authorize educational savings accounts to invite parents to abandon public schools.

“School choice” sounds like it offers options. But my new INET Working Paper shows that the whole concept, as first implemented in the U.S. South in the mid-1950s in defiance of Brown v. Board of Education, aimed to block the choice of equal, integrated education for Black families. Further, Milton Friedman, soon to become the best-known neoliberal economist in the world, abetted the push for private schooling that states in the U.S. South used to evade the reach of the ruling, which only applied to public schools. So, too, did other libertarians endorse the segregationist tool, including founders of the cause that today avidly pushes private schooling. Among them were Friedrich Hayek, Murray Rothbard, Robert Lefevre, Isabel Patterson, Felix Morley, Henry Regnery, trustees of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), and the William Volker Fund, which helped underwrite the American wing of the Mont Pelerin Society, the nerve center of neoliberalism.

Friedman and his allies saw in the backlash to the desegregation decree an opportunity they could leverage to advance their goal of privatizing government services and resources. Whatever their personal beliefs about race and racism, they helped Jim Crow survive in America by providing ostensibly race-neutral arguments for tax subsidies to the private schools sought by white supremacists.

More here.

James Meadway in New Statesman:

James Meadway in New Statesman:

Stagflation”, an appropriately ugly word coined in the 1970s to describe the grisly combination of high inflation and low growth that afflicted that decade, is making a return to economic discussion. Nouriel Roubini, the “Doctor Doom” credited with predicting the 2008 financial crash, has suggested that the “mild stagflation” of earlier this year could be followed by a more serious recurrence in the future. As I’ve written in the New Statesman over the past 18 months, endemic Covid alone would be enough to drive up costs and therefore prices across the world. The economic outlook is uniformly grim – perhaps more so than even Roubini thinks.

First, while inflation is higher than it has been, and is likely to remain so, this is not the result of the extraordinary expansion of the money supply over the past year, as most “inflation hawks” have argued. Their theory seems simple – more money chasing the same goods makes prices go up – but in reality the volumes of Quantitative Easing (QE) cash that central banks such as the Bank of England have issued since early last year have made their way into different forms of hoarding, rather than spending.

The British government has spent, for example, extraordinary amounts on the furlough scheme and, in effect, paid for it with QE. But with households having saved an estimated £200bn since the start of the pandemic, that money is not entering the wider economy and so is having limited impact on prices. The injection of QE into the financial system has only caused prices to rise in specific markets – helping to support rising house prices in the UK and US stock markets.

The causes of the current general rise in prices are more serious, and harder to solve. The supply chain disruptions caused by Covid are obvious contributing factors, with the shock of lockdowns and factory closures last year still making their way through the system. But the ongoing, and perhaps permanent, impact of Covid as the virus becomes endemic – with people continuing to fall ill, being forced to self-isolate, and the extra costs and hassles of performing many economic activities – will result in significant costs across the economy.

More here.

Michael C. Behrent in Dissent:

Suddenly, it seems, everyone has a lot to say about Michel Foucault. And much of it isn’t pretty. After enjoying a decades-long run as an all-purpose reference point in the humanities and social sciences, the French philosopher has come in for a reevaluation by both the right and the left.

The right, of course, has long blamed Foucault for licensing an array of left-wing pathologies. Some conservatives have even made Foucault a catchall scapegoat for ills ranging from slacker nihilism to woke totalitarianism. But a strange new respect is emerging for Foucault in some precincts on the right. Conservatives have flirted with the notion that Foucault’s hostility to confessional politics could make him a useful shield against “social justice warriors.” This presumption was strengthened during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Foucault’s critique of “biopolitics”—his term for the political significance assumed by public-health and medical issues in modern times—provided a handy weapon for attacking liberal fealty to scientific expertise.

As Foucault’s standing has climbed on the right, it has fallen on the left. A decade ago, left attention focused on whether Foucault’s discussions of neoliberalism in the 1970s suggested that his philosophical commitments harmonized with the emergent free-market ideology: hostile to the state, opposed to disciplinary power, and tolerant of behaviors previously deemed immoral. (In full disclosure, I contributed to this debate.) Recently, the locus of the leftist critique has, like its conservative counterpart, shifted to cultural politics. Thus the social theorists Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora maintain that Foucault’s politicization of selfhood inspired the confessional antics of “woke culture,” which seeks to overcome societal ills by making the reform of one’s self the ultimate managerial project. At the same time, Foucault’s standing has suffered a debilitating blow in the wake of recent claims that he paid underage boys for sex while living in Tunisia during the 1960s. These charges have brought new attention to places in his writing where—like some other radicals of his era—he questioned the need for a legal age of consent.

More here.

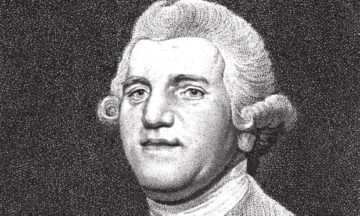

Rowan Moore at The Guardian:

There are designers and there are designers. There are those who create beautiful objects and invent new techniques, some who transform taste, some who make a good business out of what may or may not be great products, some whose greatest talents are in selling. Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95) was all of the above, and more.

There are designers and there are designers. There are those who create beautiful objects and invent new techniques, some who transform taste, some who make a good business out of what may or may not be great products, some whose greatest talents are in selling. Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95) was all of the above, and more.

It wasn’t just that he endlessly experimented with chemicals and minerals, and with kiln temperatures and firing times, to revolutionise the ceramic industry, or that he had a sharp and exacting eye for the elegance of the vases and dinner services and medallions that his company made, but also that he pioneered new ways of getting them to buyers all over the world, of marketing them, of product placement and branding. He became very rich as a result.

more here.

Marcel Theroux at the NYT:

“Cloud Cuckoo Land,” a follow-up to Doerr’s best-selling novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” is, among other things, a paean to the nameless people who have played a role in the transmission of ancient texts and preserved the tales they tell. But it’s also about the consolations of stories and the balm they have provided for millenniums. It’s a wildly inventive novel that teems with life, straddles an enormous range of experience and learning, and embodies the storytelling gifts that it celebrates. It also pulls off a resolution that feels both surprising and inevitable, and that compels you back to the opening of the book with a head-shake of admiration at the Swiss-watchery of its construction.

“Cloud Cuckoo Land,” a follow-up to Doerr’s best-selling novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” is, among other things, a paean to the nameless people who have played a role in the transmission of ancient texts and preserved the tales they tell. But it’s also about the consolations of stories and the balm they have provided for millenniums. It’s a wildly inventive novel that teems with life, straddles an enormous range of experience and learning, and embodies the storytelling gifts that it celebrates. It also pulls off a resolution that feels both surprising and inevitable, and that compels you back to the opening of the book with a head-shake of admiration at the Swiss-watchery of its construction.

The novel follows five characters in three different historical epochs, who at first seem like the protagonists of separate books.

more here.

Emma Green in The Atlantic:

“Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right.

“Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right.

As Donald Trump rose to power, the Claremont universe—which sponsors fellowships and publications, including the Claremont Review of Books and The American Mind—rose with him, publishing essays that seemed to capture why the president appealed to so many Americans and attempting to map a political philosophy onto his presidency. Williams and his cohort are on a mission to tear down and remake the right; they believe that America has been riven into two fundamentally different countries, not least because of the rise of secularism. “The Founders were pretty unanimous, with Washington leading the way, that the Constitution is really only fit for a Christian people,” Williams told me. It’s possible that violence lies ahead. “I worry about such a conflict,” Williams told me. “The Civil War was terrible. It should be the thing we try to avoid almost at all costs.”

That almost is worth noticing. “The ideal endgame would be to effect a realignment of our politics and take control of all three branches of government for a generation or two,” Williams said. Trump has left office, at least for now, but those he inspired are determined to recapture power in American politics.

More here.

Perri Klass in Smithsonian:

Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.

Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.

In 1821, a French physician, Pierre Bretonneau, gave the disease a name: diphtérite. He based it on the Greek word diphthera, for leather—a reference to the affliction’s signature physical feature, a thick, leathery buildup of dead tissue in a patient’s throat, which makes breathing and swallowing difficult, or impossible. And children, with their relatively small airways, were particularly vulnerable.

…Then, toward the end of the 19th century, scientists started identifying the bacteria that caused this human misery—giving the pathogen a name and delineating its poisonous weapon. It was diphtheria that led researchers around the world to unite in an unprecedented effort, using laboratory investigations to come up with new treatments for struggling, suffocating victims. And it was diphtheria that prompted doctors and public health officials to coordinate their efforts in cities worldwide, taking much of the terror out of a deadly disease.

More here.

There’s a man who cares

for the last snail of its kind,

Achatinella apexfulva, knows precisely

how much moisture, shade and light

it needs to thrive while it spends

its dwindling time in a glass cabinet.

Don’t think about what you can start,

think about what you can end was the advice

I heard on a time management podcast

while slicing bananas

for my daughter’s breakfast.

The banana comes from Guatemala

where its kind is plagued

by the Fusarium fungus to a possible

almost certain if-it-continues

at-this-rate extinction.

I’ve never been to Guatemala,

seen a rotting banana plant, or touched

a snail’s glossy shell of the kind

that resembles the palette

of a chocolate box— dark brown, chestnut,

white, the occasional splash of mint.

I watch my daughter collect stones

in her plastic bucket, clinking them beside her

as she runs smiling from one corner

of our yard to another — impossible to say

Jonathan Haidt in Persuasion:

In the last few years, I have had dozens of conversations with leaders of companies and nonprofit organizations about the illiberalism that is making their work so much harder. Or rather, I should say I’ve had one conversation—the same conversation—dozens of times, because the internal dynamics are so similar across organizations. I think I can explain what is now happening in nearly all of the industries that are creative or politically progressive by telling you about what happened to American universities in the mid-2010s. And I can best illustrate this change by recounting the weirdest week I ever had in my 26 years as a professor.

In the last few years, I have had dozens of conversations with leaders of companies and nonprofit organizations about the illiberalism that is making their work so much harder. Or rather, I should say I’ve had one conversation—the same conversation—dozens of times, because the internal dynamics are so similar across organizations. I think I can explain what is now happening in nearly all of the industries that are creative or politically progressive by telling you about what happened to American universities in the mid-2010s. And I can best illustrate this change by recounting the weirdest week I ever had in my 26 years as a professor.

More here.

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

America’s frustrating inability to learn from the recent past shouldn’t be surprising to anyone familiar with the history of public health. Almost 20 years ago, the historians of medicine Elizabeth Fee and Theodore Brown lamented that the U.S. had “failed to sustain progress in any coherent manner” in its capacity to handle infectious diseases. With every new pathogen—cholera in the 1830s, HIV in the 1980s—Americans rediscover the weaknesses in the country’s health system, briefly attempt to address the problem, and then “let our interest lapse when the immediate crisis seems to be over,” Fee and Brown wrote. The result is a Sisyphean cycle of panic and neglect that is now spinning in its third century. Progress is always undone; promise, always unfulfilled. Fee died in 2018, two years before SARS-CoV-2 arose. But in documenting America’s past, she foresaw its pandemic present—and its likely future.

America’s frustrating inability to learn from the recent past shouldn’t be surprising to anyone familiar with the history of public health. Almost 20 years ago, the historians of medicine Elizabeth Fee and Theodore Brown lamented that the U.S. had “failed to sustain progress in any coherent manner” in its capacity to handle infectious diseases. With every new pathogen—cholera in the 1830s, HIV in the 1980s—Americans rediscover the weaknesses in the country’s health system, briefly attempt to address the problem, and then “let our interest lapse when the immediate crisis seems to be over,” Fee and Brown wrote. The result is a Sisyphean cycle of panic and neglect that is now spinning in its third century. Progress is always undone; promise, always unfulfilled. Fee died in 2018, two years before SARS-CoV-2 arose. But in documenting America’s past, she foresaw its pandemic present—and its likely future.

More Americans have been killed by the new coronavirus than the influenza pandemic of 1918, despite a century of intervening medical advancement.

More here.

Francice Prose at Lapham’s Quarterly:

In case we wonder why not all of us have healthy, sustaining, lifelong friendships, this issue offers some answers to the riddle of why and how friendships, begun in such pleasure and good faith, can derail so catastrophically.

In case we wonder why not all of us have healthy, sustaining, lifelong friendships, this issue offers some answers to the riddle of why and how friendships, begun in such pleasure and good faith, can derail so catastrophically.

Obviously, one threat to friendship is death, the built-in drawback to any cherished human connection. Composed in the second millennium, Gilgamesh’s haunting lament for his friend Enkidu makes us realize how little grief and mourning have changed in four thousand years. Saint Augustine is nearly destroyed by sorrow over the death of a friend: “I hated everything, because nothing had him in it, and nothing could now say to me, ‘Look, he’s coming.’ ”

The moral, as always, is that if you’re afraid of losing friends, it’s probably better not to have any.

more here.

Madiha Tahir in the Boston Review:

The United States began bombing the border zone, then known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), in 2004, ostensibly to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It has bombed the area at least 430 times, according to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalists, and killed anywhere between 2,515 to 4,026 people.

The United States began bombing the border zone, then known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), in 2004, ostensibly to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It has bombed the area at least 430 times, according to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalists, and killed anywhere between 2,515 to 4,026 people.

But the United States is not the only force bombing the region. Between 2008 to 2011 alone, the Pakistan Air Force carried out 5,500 bombing runs and dropped 10,600 bombs. The Pakistani security forces have also conducted scores of major military operations in the Tribal Areas as well as other Pashtun regions. There is no detailed accounting of the human costs of these military assaults.

More here.

Steven Nadler at Literary Review:

The term ‘atheist’ can be just as ambiguous as ‘religious’ and ‘God’. In the 17th century, it was essentially an all-purpose word used against anyone whose view of God departed from orthodoxy – much in the way that ‘communist’ was (and is) used in the USA to cast aspersion on political opponents (and much in the way that ‘Spinozist’ was used in the early modern period after Spinoza’s works were posthumously published and condemned). But Spinoza does not only dismantle the orthodox notion of a personal God, which he regards as a source of human misery. He also famously refers to ‘God or Nature’ (Deus sive Natura), which suggests that God is nothing but nature, and that ‘God’ can broadly be construed to refer both to the visible cosmos and to the unseen but fundamental power, laws and principles that govern it. And this, to me at least, looks like true atheism. In Spinoza’s view, all there is is nature. There is no supernatural; there is nothing that does not belong to nature and that is not subject to its causal processes.

The term ‘atheist’ can be just as ambiguous as ‘religious’ and ‘God’. In the 17th century, it was essentially an all-purpose word used against anyone whose view of God departed from orthodoxy – much in the way that ‘communist’ was (and is) used in the USA to cast aspersion on political opponents (and much in the way that ‘Spinozist’ was used in the early modern period after Spinoza’s works were posthumously published and condemned). But Spinoza does not only dismantle the orthodox notion of a personal God, which he regards as a source of human misery. He also famously refers to ‘God or Nature’ (Deus sive Natura), which suggests that God is nothing but nature, and that ‘God’ can broadly be construed to refer both to the visible cosmos and to the unseen but fundamental power, laws and principles that govern it. And this, to me at least, looks like true atheism. In Spinoza’s view, all there is is nature. There is no supernatural; there is nothing that does not belong to nature and that is not subject to its causal processes.

more here.