by Emrys Westacott

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

- A person’s approach to work reveals something of their moral character.

- The activity of working itself fosters certain important moral virtues.

The first idea, that moral character is expressed through work, itself contains two distinct claims.

First, workers are seen as morally superior to shirkers. Being willing to work hard, to take on difficult or unrewarding tasks, to do one’s fair share, to go “above and beyond” one’s basic obligations, are almost universally viewed as admirable qualities. To be sure, a couple of caveats are in order. The old saw that “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, ” while not exactly a moral remonstrance, is a reminder of the need for balance in life, both for an individual’s wellbeing and for that of those closest to them. In addition, one can easily imagine some situations where a person’s zeal at work may be viewed by their peers unfavorably. “Swots” in school are often unpopular. Employees who look to impress their supervisors with how hard they work may be resented by their workmates for raising what is expected of everyone else, and for having embraced the values of capital (standing out and getting on) rather than of labour (solidarity). In general, though, and especially in any social setting–school, workplace, household, playing field, or voluntary institution–a willingness to work hard is typically applauded.

Second, how a person works is also widely viewed as revealing something about their moral character. Most obviously, diligence, conscientiousness, and the careful exercise of skills acquired laboriously are often taken to be morally significant. Just as such things as literacy, problem solving, or personnel management are considered “transferable skills” that can be deployed in many different contexts, so the qualities just mentioned are often viewed as what might be called “transferable virtues”: traits that will render someone valuable to have around and worthy of moral esteem. (By contrast, “transferable vices” would include sloppiness, lack of attention to detail, not being bothered to learn what is necessary for a task, and willingness to settle for second or third rate outcomes.)

How much validity is there to such inferences about transferable virtues? Read more »

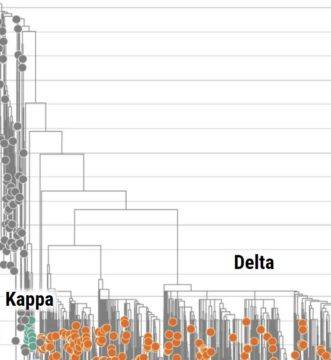

Edward Holmes does not like making predictions, but last year he hazarded a few. Again and again, people had asked Holmes, an expert on viral evolution at the University of Sydney, how he expected SARS-CoV-2 to change. In May 2020, 5 months into the pandemic, he started to include a slide with his best guesses in his talks. The virus would probably evolve to avoid at least some human immunity, he suggested. But it would likely make people less sick over time, he said, and there would be little change in its infectivity. In short, it sounded like evolution would not play a major role in the pandemic’s near future.

Edward Holmes does not like making predictions, but last year he hazarded a few. Again and again, people had asked Holmes, an expert on viral evolution at the University of Sydney, how he expected SARS-CoV-2 to change. In May 2020, 5 months into the pandemic, he started to include a slide with his best guesses in his talks. The virus would probably evolve to avoid at least some human immunity, he suggested. But it would likely make people less sick over time, he said, and there would be little change in its infectivity. In short, it sounded like evolution would not play a major role in the pandemic’s near future. Exactly one year ago, I did not die from poisoning by a chemical weapon, and it would seem that corruption played no small part in my survival. Having contaminated Russia’s state system, corruption has also contaminated the intelligence services. When a country’s senior management is preoccupied with protection rackets and extortion from businesses, the quality of covert operations inevitably suffers. A group of FSB agents applied the nerve agent to my underwear just as shoddily as they incompetently dogged my footsteps for three and a half years – in violation of all instructions from above – allowing

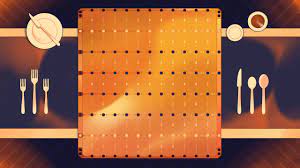

Exactly one year ago, I did not die from poisoning by a chemical weapon, and it would seem that corruption played no small part in my survival. Having contaminated Russia’s state system, corruption has also contaminated the intelligence services. When a country’s senior management is preoccupied with protection rackets and extortion from businesses, the quality of covert operations inevitably suffers. A group of FSB agents applied the nerve agent to my underwear just as shoddily as they incompetently dogged my footsteps for three and a half years – in violation of all instructions from above – allowing  Deep learning, the artificial-intelligence technology that powers voice assistants, autonomous cars, and Go champions, relies on complicated “neural network” software arranged in layers. A deep-learning system can live on a single computer, but the biggest ones are spread over thousands of machines wired together into “clusters,” which sometimes live at large data centers, like those operated by Google. In a big cluster, as many as forty-eight pizza-box-size servers slide into a rack as tall as a person; these racks stand in rows, filling buildings the size of warehouses. The neural networks in such systems can tackle daunting problems, but they also face clear challenges. A network spread across a cluster is like a brain that’s been scattered around a room and wired together. Electrons move fast, but, even so, cross-chip communication is slow, and uses extravagant amounts of energy.

Deep learning, the artificial-intelligence technology that powers voice assistants, autonomous cars, and Go champions, relies on complicated “neural network” software arranged in layers. A deep-learning system can live on a single computer, but the biggest ones are spread over thousands of machines wired together into “clusters,” which sometimes live at large data centers, like those operated by Google. In a big cluster, as many as forty-eight pizza-box-size servers slide into a rack as tall as a person; these racks stand in rows, filling buildings the size of warehouses. The neural networks in such systems can tackle daunting problems, but they also face clear challenges. A network spread across a cluster is like a brain that’s been scattered around a room and wired together. Electrons move fast, but, even so, cross-chip communication is slow, and uses extravagant amounts of energy. W

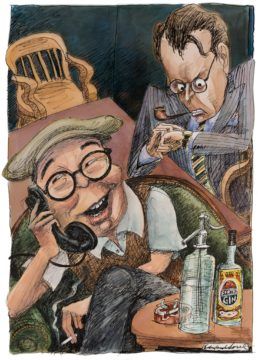

W In the rat-infested trenches of France, Raymond Chandler became an alcoholic, and stayed one. In 1932, after booze had gotten him fired from a cushy job, he resolved to cut down on the gin and become a novelist. He began by selling hard-boiled detective yarns to the pulpy magazine Black Mask, then later sold his first novel, “The Big Sleep,” to Alfred A. Knopf. In 1943, Chandler’s third novel, “The High Window,” was read by the Paramount director Billy Wilder. He liked the way Chandler wrote dialogue, and offered him a contract of $750 a week for 10 weeks to work with him on a screenplay for “Double Indemnity,” James M. Cain’s novel. Chandler had never written for the screen, and didn’t like the idea of being subservient to a young Austrian-born Jew who had written dozens of screenplays in Berlin and Hollywood. But Chandler was broke, and had a sick wife to care for. He signed up.

In the rat-infested trenches of France, Raymond Chandler became an alcoholic, and stayed one. In 1932, after booze had gotten him fired from a cushy job, he resolved to cut down on the gin and become a novelist. He began by selling hard-boiled detective yarns to the pulpy magazine Black Mask, then later sold his first novel, “The Big Sleep,” to Alfred A. Knopf. In 1943, Chandler’s third novel, “The High Window,” was read by the Paramount director Billy Wilder. He liked the way Chandler wrote dialogue, and offered him a contract of $750 a week for 10 weeks to work with him on a screenplay for “Double Indemnity,” James M. Cain’s novel. Chandler had never written for the screen, and didn’t like the idea of being subservient to a young Austrian-born Jew who had written dozens of screenplays in Berlin and Hollywood. But Chandler was broke, and had a sick wife to care for. He signed up. Chris Lehmann in The New Republic:

Chris Lehmann in The New Republic: THE UNITED STATES has forgotten the hobo. We recognize the problem of homelessness, but the rootless rambler who steals rides on freight trains seems a relic of a long gone past. Even the word itself, hobo, is outdated. The same goes for the word tramp, which, if used at all tends to be for slut-shaming purposes. The term bum remains, but it, too, is derogatory, perhaps only acceptable as a verb, as in, “Can I bum a smoke?”

THE UNITED STATES has forgotten the hobo. We recognize the problem of homelessness, but the rootless rambler who steals rides on freight trains seems a relic of a long gone past. Even the word itself, hobo, is outdated. The same goes for the word tramp, which, if used at all tends to be for slut-shaming purposes. The term bum remains, but it, too, is derogatory, perhaps only acceptable as a verb, as in, “Can I bum a smoke?” Emilie Bickerton in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Emilie Bickerton in the NLR’s Sidecar: Kim Stanley Robinson in the FT:

Kim Stanley Robinson in the FT: T

T