Nicholas Frankel in Literary Hub:

Oscar Wilde’s ship docked in New York Harbor on the evening of January 2, 1882, one week before he was scheduled to speak at Chickering Hall. During the crossing he had composed his first lecture, but the journalists who swarmed onto the ship as it lay at anchor off Staten Island were more interested in Wilde himself than in the theories he had come to expound. “His outer garment was a long ulster trimmed with two kinds of fur, which reached almost to his feet,” reported the New York World; “he wore patent-leather shoes, a smoking-cap or turban, and his shirt might be termed ultra-Byronic . . . His hair flowed over his shoulders in dark-brown waves, curling slightly upwards at the ends . . . His teeth were large and regular, disproving a pleasing story which has gone the rounds of the English press that he has three tusks or protuberants.” His face presented “an exaggerated oval of the Italian face carried into the English type of countenance,” the World reporter continued, while his “manner of talking” was “somewhat affected . . . his great peculiarity being a rhythmical chant in which every fourth syllable is accentuated.” “The dress of the poet was not less remarkable than his face,” declared the San Francisco Chronicle, “and consisted of a short velvet coat, rose-colored necktie and dark-brown trousers . . . cut with a sublime disregard of the latest fashion.”

Oscar Wilde’s ship docked in New York Harbor on the evening of January 2, 1882, one week before he was scheduled to speak at Chickering Hall. During the crossing he had composed his first lecture, but the journalists who swarmed onto the ship as it lay at anchor off Staten Island were more interested in Wilde himself than in the theories he had come to expound. “His outer garment was a long ulster trimmed with two kinds of fur, which reached almost to his feet,” reported the New York World; “he wore patent-leather shoes, a smoking-cap or turban, and his shirt might be termed ultra-Byronic . . . His hair flowed over his shoulders in dark-brown waves, curling slightly upwards at the ends . . . His teeth were large and regular, disproving a pleasing story which has gone the rounds of the English press that he has three tusks or protuberants.” His face presented “an exaggerated oval of the Italian face carried into the English type of countenance,” the World reporter continued, while his “manner of talking” was “somewhat affected . . . his great peculiarity being a rhythmical chant in which every fourth syllable is accentuated.” “The dress of the poet was not less remarkable than his face,” declared the San Francisco Chronicle, “and consisted of a short velvet coat, rose-colored necktie and dark-brown trousers . . . cut with a sublime disregard of the latest fashion.”

Like modern tabloid journalists, they peppered him with questions both flippant and straight: what time did he get up in the morning? Did he like his eggs fried on both sides or just one? Did he trim his fingernails in the style of the Empress of Japan? Was he here to secure copyright in his play? If Wilde was thrown by this barrage of questions, he did not betray it.

More here.

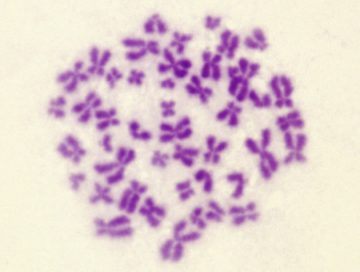

Two decades after the draft sequence of the human genome was

Two decades after the draft sequence of the human genome was  A new study tracking the planet’s vital signs has found that many of the key indicators of the global climate crisis are getting worse and either approaching, or exceeding, key tipping points as the earth heats up.

A new study tracking the planet’s vital signs has found that many of the key indicators of the global climate crisis are getting worse and either approaching, or exceeding, key tipping points as the earth heats up. Facebook has a save-the-world mission statement—“to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together”—that sounds like a better fit for a church, and not some little wood-steepled, white-clapboarded, side-of-the-road number but a castle-in-a-parking-lot megachurch, a big-as-a-city-block cathedral, or, honestly, the Vatican.

Facebook has a save-the-world mission statement—“to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together”—that sounds like a better fit for a church, and not some little wood-steepled, white-clapboarded, side-of-the-road number but a castle-in-a-parking-lot megachurch, a big-as-a-city-block cathedral, or, honestly, the Vatican.  More than two decades ago, when Elizabeth Turner was still a graduate student studying fossilized microbial reefs, she hammered out hundreds of lemon-sized rocks from weathered cliff faces in Canada’s Northwest Territories. She hauled her rocks back to the lab, sawed them into 30-micron-thick slivers—about half the diameter of human hair—and scrutinized her handiwork under a microscope. Only in about five of the translucent slices, she found a sea of slender squiggles that looked nothing like the microbes she was after. “It just didn’t fit. The microstructure was too complicated,” says Turner. “And it looked to me kind of familiar.”

More than two decades ago, when Elizabeth Turner was still a graduate student studying fossilized microbial reefs, she hammered out hundreds of lemon-sized rocks from weathered cliff faces in Canada’s Northwest Territories. She hauled her rocks back to the lab, sawed them into 30-micron-thick slivers—about half the diameter of human hair—and scrutinized her handiwork under a microscope. Only in about five of the translucent slices, she found a sea of slender squiggles that looked nothing like the microbes she was after. “It just didn’t fit. The microstructure was too complicated,” says Turner. “And it looked to me kind of familiar.” “T

“T I do not want to be soft-minded or irrational, pursue Dark Aged–ignorance, be any sort of woo-woo New Age mush head. I do not know my moon sign. I own a Tarot deck but do not know how to read the cards. I don’t know much about prayer, though I have aimed begging attention at thunderstorms to come, please come, break this heat, rip it open. I believe, in some ferocious kid place, that there’s a lot on this earth and beyond it that we don’t understand. No correlation? Maybe, instead, the more honest: we don’t know, we have not figured a way to measure, or to say. “Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot?” Bram Stoker asks. “It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Stephen Jay Gould had a name for this, when scientists interpret an absence of discernible change as no data, leaving significant signals from nature unseen, unreported, ignored.

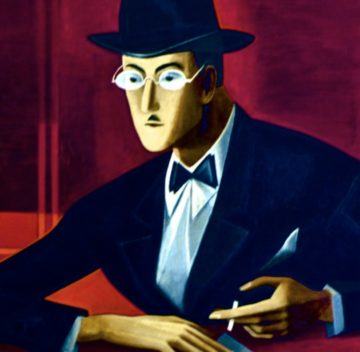

I do not want to be soft-minded or irrational, pursue Dark Aged–ignorance, be any sort of woo-woo New Age mush head. I do not know my moon sign. I own a Tarot deck but do not know how to read the cards. I don’t know much about prayer, though I have aimed begging attention at thunderstorms to come, please come, break this heat, rip it open. I believe, in some ferocious kid place, that there’s a lot on this earth and beyond it that we don’t understand. No correlation? Maybe, instead, the more honest: we don’t know, we have not figured a way to measure, or to say. “Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot?” Bram Stoker asks. “It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Stephen Jay Gould had a name for this, when scientists interpret an absence of discernible change as no data, leaving significant signals from nature unseen, unreported, ignored. When the ever elusive Fernando Pessoa died in Lisbon, in the fall of 1935, few people in Portugal realized what a great writer they had lost. None of them had any idea what the world was going to gain: one of the richest and strangest bodies of literature produced in the twentieth century. Although Pessoa lived to write and aspired, like poets from Ovid to Walt Whitman, to literary immortality, he kept his ambitions in the closet, along with the larger part of his literary universe. He had published only one book of his Portuguese poetry, Mensagem (Message), with forty-four poems, in 1934. It won a dubious prize from António Salazar’s autocratic regime, for poetic works denoting “a lofty sense of nationalist exaltation,” and dominated his literary résumé at the time of his death.

When the ever elusive Fernando Pessoa died in Lisbon, in the fall of 1935, few people in Portugal realized what a great writer they had lost. None of them had any idea what the world was going to gain: one of the richest and strangest bodies of literature produced in the twentieth century. Although Pessoa lived to write and aspired, like poets from Ovid to Walt Whitman, to literary immortality, he kept his ambitions in the closet, along with the larger part of his literary universe. He had published only one book of his Portuguese poetry, Mensagem (Message), with forty-four poems, in 1934. It won a dubious prize from António Salazar’s autocratic regime, for poetic works denoting “a lofty sense of nationalist exaltation,” and dominated his literary résumé at the time of his death.

‘The greatest living theoretical physicist’ – many commentators in the past few decades have described Steven Weinberg in such terms. When I rather cheekily asked him what he thought of that statement, he shot back: ‘It is quite ridiculous to rank scientists like that’, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘but it would be impolite to dispute the conclusion’. That reply was classic Weinberg: self-aware, intimidatingly direct but always ready to lighten the moment with humour.

‘The greatest living theoretical physicist’ – many commentators in the past few decades have described Steven Weinberg in such terms. When I rather cheekily asked him what he thought of that statement, he shot back: ‘It is quite ridiculous to rank scientists like that’, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘but it would be impolite to dispute the conclusion’. That reply was classic Weinberg: self-aware, intimidatingly direct but always ready to lighten the moment with humour. Elaine Scarry has been writing about the unique dangers and challenges of nuclear weapons in Boston Review for

Elaine Scarry has been writing about the unique dangers and challenges of nuclear weapons in Boston Review for  Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College.

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. P

P Knowledge is so often assumed to be a good thing, particularly by philosophers, that we don’t think enough about when it makes sense to not want it. Perhaps you’re a parent and want to give your children space: you might be glad to not know all that they do when out of your sight. Perhaps you want to reconcile politically with a group that’s committed violence: it might be easier to move on if you deliberately spare yourself all the details of what they’ve done. There are, in fact, a variety of reasons why one might reasonably choose ignorance. One of the most obvious is to avoid needless pain.

Knowledge is so often assumed to be a good thing, particularly by philosophers, that we don’t think enough about when it makes sense to not want it. Perhaps you’re a parent and want to give your children space: you might be glad to not know all that they do when out of your sight. Perhaps you want to reconcile politically with a group that’s committed violence: it might be easier to move on if you deliberately spare yourself all the details of what they’ve done. There are, in fact, a variety of reasons why one might reasonably choose ignorance. One of the most obvious is to avoid needless pain. Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators

Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators