Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

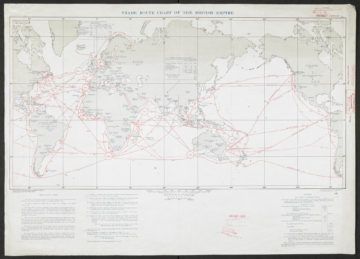

During the first era of globalization (1870–1913), the global division of labor was stark. Britain and other Western nations largely produced manufactured goods, but they also exported a whole range of temperate agricultural goods like wheat, beef and barley. Elsewhere in the European colonial empires, products like cotton, cocoa and coffee were exported, often at very low prices and sometimes with forced labor, to sate a growing demand in the global economic core for tropical luxuries. More than a century has passed since World War I heralded the collapse of this world order. Today, the globalization wave that has shaped the world since the 1980s is ebbing.

What is the legacy of the First Globalization of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries on the economic fortunes of countries during the Second Globalization? To what extent have countries’ positions in the international economic order been persistent across the two globalizations, with some trapped at the bottom and others comfortably on top?

Long-term development trajectories are commonly explained through the convergence hypothesis. Derived from neoclassical growth theory, it states that “initial conditions have no implications for the long-run distribution of per capita income.” The hypothesis suggests that history has no persistent bearing on countries’ relative wealth: if left to the laws of the market, poorer countries are expected to catch up by outperforming richer countries in their rates of economic growth. However, the convergence hypothesis is not backed by empirical evidence—extensive testing has not heralded the results that standard growth theory would expect. In an effort to elucidate these findings, a quickly growing “persistence literature” has proposed a range of explanations for why countries’ relative wealth today is historically rooted in institutional quality (referring in this case to property rights regimes and liberal representative democracy), culture, religion, geography, or even genetics.

More here.