Janique Vigier in Bookforum:

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

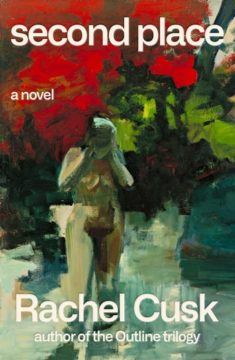

Second Place, Cusk’s latest novel, begins from the perch of moral certainty, and never quite lets go. A psychosexual drama with no sex, the book revolves around two characters, referred to only as L and M. L is a male artist, M a female patron. The novel centers around the questions these differences reveal. Or, closer to the truth: these questions and differences reveal Cusk’s predetermined moral universe. Questions are illusory; there are deterministic stances. The standpoint of the main characters reflects this. L, fey and ascetic, is a thinly disguised version of D. H. Lawrence, whom Cusk has called her mentor. L is a painter, not a writer, but the specter of Male Genius is made clear. His foil, M, the writer-narrator, reveres his paintings, seeing him, by extension, as a kind of oracle. She makes the natural assumption and casual error of conflating the virtues of the work with the character of the artist. Cusk’s own devotion to Lawrence makes these metatextual tricks all the more fraught. Is there a more intimate and controlling way to pay homage to your literary idol than by turning him into a fictional character?

It’s a funny time to write a novel about Lawrence, though not necessarily more so than any other: too romantic to be modern, accused by his contemporaries of being a pornographer—that is, part of the avant-garde—he has never been contemporary, not even in his own time. A man whose tragedy, according to Angela Carter, was that “he thought he was a man,” a pious man who wrote frankly about sex, Lawrence suffered his aloneness. Poor, childless, mostly itinerant, he shares little biographical similarity with Cusk, who has turned her children, her career success, and her home into subjects for her fiction. What the two writers do share is a basic and unassailable belief in the individual, a belief that underwrites their obsessive preoccupation with will, intuition, and transformation. Above all it’s women—as question and problem—that drive their work and fetter their hearts. How can women give voice to themselves? What can love look like? And freedom?

More here.