Nathan Taylor Pemberton at Bookforum:

Earlier in his career, Gregory writes, theater was a “drug to relieve the pain of living.” But escaping into his “calling” came with no shortage of throbbing side effects. One of the “most awful” days of Gregory’s life is the one when he directs a scene at Strasberg’s Actors Studio only to receive a brutal critique from the famed teacher in front of his fellow students, among them Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman. (He’d stay away from Strasberg’s class for months.) The belated success of his Alice came only after a succession of early failures: being fired from three consecutive directorships at small regional theaters. An “enfant terrible” in these years, Gregory hired a chemist to synthesize the smell of “rotting flesh” for a production in Philadelphia, resulting in an actor vomiting during a tech rehearsal and Gregory’s dismissal from the play. Another firing, from a theater in Los Angeles, came after he was punched by the program’s benefactor, the movie star Gregory Peck.

Earlier in his career, Gregory writes, theater was a “drug to relieve the pain of living.” But escaping into his “calling” came with no shortage of throbbing side effects. One of the “most awful” days of Gregory’s life is the one when he directs a scene at Strasberg’s Actors Studio only to receive a brutal critique from the famed teacher in front of his fellow students, among them Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman. (He’d stay away from Strasberg’s class for months.) The belated success of his Alice came only after a succession of early failures: being fired from three consecutive directorships at small regional theaters. An “enfant terrible” in these years, Gregory hired a chemist to synthesize the smell of “rotting flesh” for a production in Philadelphia, resulting in an actor vomiting during a tech rehearsal and Gregory’s dismissal from the play. Another firing, from a theater in Los Angeles, came after he was punched by the program’s benefactor, the movie star Gregory Peck.

more here.

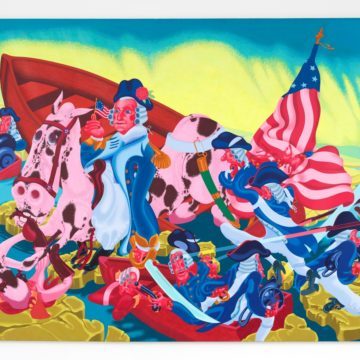

A mild sensation in the late Sixties, a cult artist in the early Aughts, and now a seasoned art world veteran, Saul, who is 86, is having a moment. “How long until Peter Saul is rediscovered once and for all,” Beau Rutland wrote on the occasion of Saul’s comprehensive 2017 show at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. European retrospectives and newly respectful reviews have culminated in a two-floor survey at the New Museum last February. It is Saul’s first retrospective in New York City, accompanied by a lavish catalog and the publication of his “professional artist correspondence,” a fascinating collection of letters written to his parents and his longtime gallerist Allan Frumkin.

A mild sensation in the late Sixties, a cult artist in the early Aughts, and now a seasoned art world veteran, Saul, who is 86, is having a moment. “How long until Peter Saul is rediscovered once and for all,” Beau Rutland wrote on the occasion of Saul’s comprehensive 2017 show at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. European retrospectives and newly respectful reviews have culminated in a two-floor survey at the New Museum last February. It is Saul’s first retrospective in New York City, accompanied by a lavish catalog and the publication of his “professional artist correspondence,” a fascinating collection of letters written to his parents and his longtime gallerist Allan Frumkin. It was 10 years ago that

It was 10 years ago that  After 35 years of sharing everything from a love for jazz music to tubes of lip gloss, twins Kimberly and Kelly Standard assumed that when they became sick with Covid-19 their experiences would be as identical as their DNA. The virus had different plans. Early last spring, the sisters from Rochester, Michigan, checked themselves into the hospital with fevers and shortness of breath. While Kelly was discharged after less than a week, her sister ended up in intensive care. Kimberly spent almost a month in critical condition, breathing through tubes and dipping in and out of shock. Weeks after Kelly had returned to their shared home, Kimberly was still relearning how to speak, walk and chew and swallow solid food she could barely taste. Nearly a year later, the sisters are bedeviled by the bizarrely divergent paths their illnesses took.

After 35 years of sharing everything from a love for jazz music to tubes of lip gloss, twins Kimberly and Kelly Standard assumed that when they became sick with Covid-19 their experiences would be as identical as their DNA. The virus had different plans. Early last spring, the sisters from Rochester, Michigan, checked themselves into the hospital with fevers and shortness of breath. While Kelly was discharged after less than a week, her sister ended up in intensive care. Kimberly spent almost a month in critical condition, breathing through tubes and dipping in and out of shock. Weeks after Kelly had returned to their shared home, Kimberly was still relearning how to speak, walk and chew and swallow solid food she could barely taste. Nearly a year later, the sisters are bedeviled by the bizarrely divergent paths their illnesses took.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with. Over the past 10 years, numerous studies have shown that our obsession with happiness and high personal confidence may be making us less content with our lives, and less effective at reaching our actual goals. Indeed, we may often be happier when we stop focusing on happiness altogether.

Over the past 10 years, numerous studies have shown that our obsession with happiness and high personal confidence may be making us less content with our lives, and less effective at reaching our actual goals. Indeed, we may often be happier when we stop focusing on happiness altogether. Spider legs seem to have minds of their own. According to findings published

Spider legs seem to have minds of their own. According to findings published