Month: May 2020

Why do some COVID-19 patients infect many others, whereas most don’t spread the virus at all?

Kai Kupferschmidt in Science:

When 61 people met for a choir practice in a church in Mount Vernon, Washington, on 10 March, everything seemed normal. For 2.5 hours the chorists sang, snacked on cookies and oranges, and sang some more. But one of them had been suffering for 3 days from what felt like a cold—and turned out to be COVID-19. In the following weeks, 53 choir members got sick, three were hospitalized, and two died, according to a 12 May report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that meticulously reconstructed the tragedy.

When 61 people met for a choir practice in a church in Mount Vernon, Washington, on 10 March, everything seemed normal. For 2.5 hours the chorists sang, snacked on cookies and oranges, and sang some more. But one of them had been suffering for 3 days from what felt like a cold—and turned out to be COVID-19. In the following weeks, 53 choir members got sick, three were hospitalized, and two died, according to a 12 May report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that meticulously reconstructed the tragedy.

Many similar “superspreading events” have occurred in the COVID-19 pandemic. A database by Gwenan Knight and colleagues at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) lists an outbreak in a dormitory for migrant workers in Singapore linked to almost 800 cases; 80 infections tied to live music venues in Osaka, Japan; and a cluster of 65 cases resulting from Zumba classes in South Korea. Clusters have also occurred aboard ships and at nursing homes, meatpacking plants, ski resorts, churches, restaurants, hospitals, and prisons. Sometimes a single person infects dozens of people, whereas other clusters unfold across several generations of spread, in multiple venues.

More here.

Beastie Boys – Glasgow 1999

Letting The Monsters In

Vanessa Place at The Hedgehog Review:

We monster: According to Johnson, we cast out. But by casting out the monster, we cast in ourselves as that which is not-monster. That’s the simple formula, a process of inclusion by way of exclusion. But if the formula is, as formulas are, an equation, then both sides are equivalent, meaning that we must monster within as without, the monster thus monstered not gotten rid of, precisely, but held as an image, a template or test to be used to identify and expel more monsters—to go on monstering. I may only monster to the extent that I myself know the monstrous. Here echoes the fascist censor’s dilemma: If I recognize a critique of the state, then have I also not understood that the state is subject to critique, thereby betraying my own latent critique of the state? Too, the more I know of the monstrous, the better still my monstering—just as the monster knows us, how foolishly soft our throats, how stupidly open our windows. There is an intimacy in this: If, when we are children, we keep our monsters tucked under the bed, when we are adults they bed us, lodging in our chests and necks, penetrating our hearts, for it is another well-worn observation that the monster, as made, represents our desires as horrors, our horrors as desires. The vampire was emblematic of the love and fear of lust, that too-much of desire; Frankenstein’s creature, the love and fear of technology, that too-much of savoir faire; our Jekyll hiding our outraging Hyde.

We monster: According to Johnson, we cast out. But by casting out the monster, we cast in ourselves as that which is not-monster. That’s the simple formula, a process of inclusion by way of exclusion. But if the formula is, as formulas are, an equation, then both sides are equivalent, meaning that we must monster within as without, the monster thus monstered not gotten rid of, precisely, but held as an image, a template or test to be used to identify and expel more monsters—to go on monstering. I may only monster to the extent that I myself know the monstrous. Here echoes the fascist censor’s dilemma: If I recognize a critique of the state, then have I also not understood that the state is subject to critique, thereby betraying my own latent critique of the state? Too, the more I know of the monstrous, the better still my monstering—just as the monster knows us, how foolishly soft our throats, how stupidly open our windows. There is an intimacy in this: If, when we are children, we keep our monsters tucked under the bed, when we are adults they bed us, lodging in our chests and necks, penetrating our hearts, for it is another well-worn observation that the monster, as made, represents our desires as horrors, our horrors as desires. The vampire was emblematic of the love and fear of lust, that too-much of desire; Frankenstein’s creature, the love and fear of technology, that too-much of savoir faire; our Jekyll hiding our outraging Hyde.

more here.

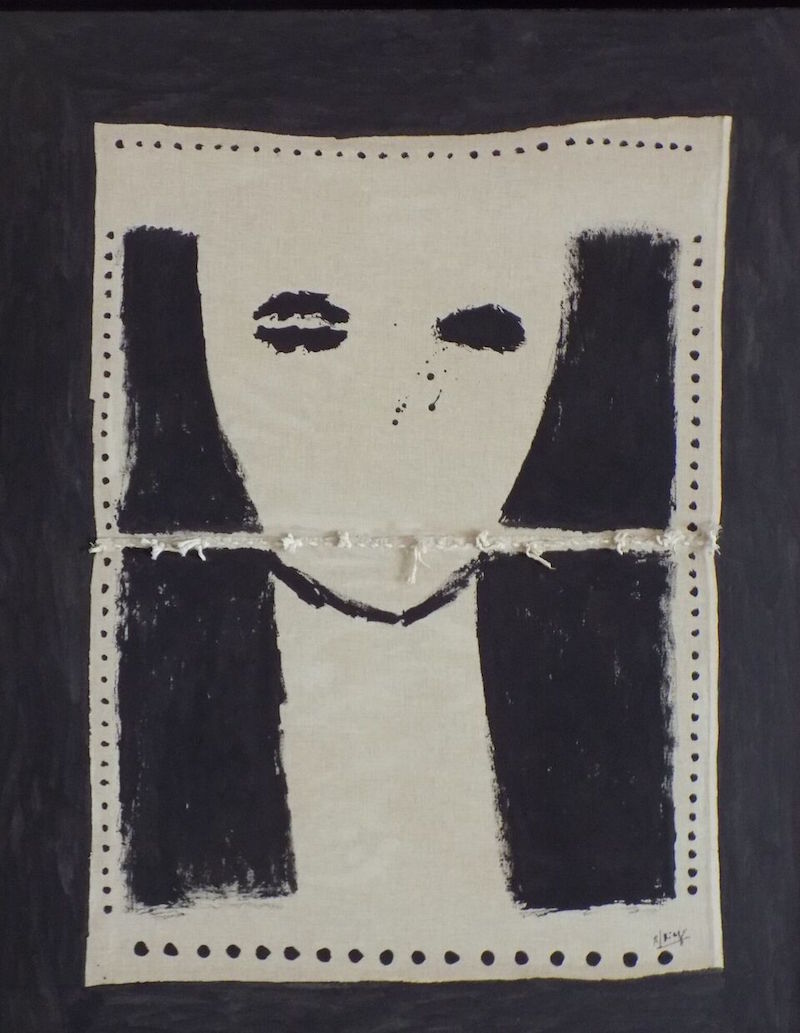

Luchita Hurtado’s Persistent Perspective

Elisa Wouk Almino at the NYRB:

It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.”

It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.”

Hurtado spent much of her life mingling with and befriending some of the twentieth century’s best-known artists. She was close to Isamu Noguchi and once attended a party in Frida Kahlo’s hospital room. When she first met Marcel Duchamp, he gave Hurtado a foot massage. Jackson Pollock “scared the hell” out of her. But none of them knew Hurtado herself was an artist.

more here.

Covid-19 might prove a “Goldilocks crisis” forcing the world to confront its problems

Jeremy Cliffe in New Statesman:

One might expect Ian Bremmer to be straightforwardly pessimistic in the current crisis. For one thing, the president of the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy is used to zipping around the world to meet business and political leaders. Now he is grounded and reckons any sort of new normal will take a very long time to emerge. “It’s weird,” he tells me down the phone from New York City. “I wasn’t prepared to put my life on hold for three years.” The US of all places is a gloomy spot at the moment, with more Covid-19 deaths than any other country and an increasingly ugly political mood ahead of November’s elections. Pessimism, of a sort, has been a good bet for Bremmer in the past. In 2011 he predicted a “G-Zero” world, an emerging power vacuum in international politics. The prediction has been borne out, he notes, both by trends evident at the time (a rising China reluctant to align with the West, a more self-contained US and a truculent Russia) and by others (technology driving populism, US energy independence, and the inequality bequeathed by the financial crisis) that have fully unfolded since.

One might expect Ian Bremmer to be straightforwardly pessimistic in the current crisis. For one thing, the president of the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy is used to zipping around the world to meet business and political leaders. Now he is grounded and reckons any sort of new normal will take a very long time to emerge. “It’s weird,” he tells me down the phone from New York City. “I wasn’t prepared to put my life on hold for three years.” The US of all places is a gloomy spot at the moment, with more Covid-19 deaths than any other country and an increasingly ugly political mood ahead of November’s elections. Pessimism, of a sort, has been a good bet for Bremmer in the past. In 2011 he predicted a “G-Zero” world, an emerging power vacuum in international politics. The prediction has been borne out, he notes, both by trends evident at the time (a rising China reluctant to align with the West, a more self-contained US and a truculent Russia) and by others (technology driving populism, US energy independence, and the inequality bequeathed by the financial crisis) that have fully unfolded since.

“They have made the geopolitical recession much deeper,” says Bremmer. “Now it’s like that Warren Buffett quote about only seeing who is swimming naked when the tide goes out. People are saying: ‘we don’t have leaders; no one is leading us!’ But that was the case before. The pandemic has just demonstrated it.” Yet precisely now, with the global order seemingly at its most fragile and unfixable, the geopolitical guru is tentatively offering a more optimistic take.

More here.

Memory in a Time of Quarantine:

Bob Grant in The Scientist:

The past couple of months have been heavy for us at The Scientist. Heavy for everyone. From our home offices, we’ve been tirelessly reporting on the global pandemic that continues to grip the world in its stranglehold. We are trying to stay atop a flood of information and stories that need telling as we also contend with challenges that most of us have never confronted, and none of us will likely soon forget. At the same time, we continue to search across the life sciences for other nuggets of research worth sharing. This month, our issue is focused on the science of memory. Our memories make us who we are, subconsciously driving our behaviors and dictating how we view the world. One of the most interesting things about memory is its imperfection. Rather than serving as a precise record of past events, our memories are more like concocted reflections, filtered and distilled from pure reality into a personal brew that is formulated by our own unique physiologies and emotional backgrounds. The wholly unique universe we each create—separate from but still tethered to the actual universe—is the product of electrical signals zapping through the lump of fatty flesh inside our skulls. Biology gives birth to something that exists outside the boundaries of biology.

The past couple of months have been heavy for us at The Scientist. Heavy for everyone. From our home offices, we’ve been tirelessly reporting on the global pandemic that continues to grip the world in its stranglehold. We are trying to stay atop a flood of information and stories that need telling as we also contend with challenges that most of us have never confronted, and none of us will likely soon forget. At the same time, we continue to search across the life sciences for other nuggets of research worth sharing. This month, our issue is focused on the science of memory. Our memories make us who we are, subconsciously driving our behaviors and dictating how we view the world. One of the most interesting things about memory is its imperfection. Rather than serving as a precise record of past events, our memories are more like concocted reflections, filtered and distilled from pure reality into a personal brew that is formulated by our own unique physiologies and emotional backgrounds. The wholly unique universe we each create—separate from but still tethered to the actual universe—is the product of electrical signals zapping through the lump of fatty flesh inside our skulls. Biology gives birth to something that exists outside the boundaries of biology.

…What scares me most at this juncture in world history is how the COVID-19 pandemic will live in the memories of those affected by it. The patchiness of the current global predicament will dictate our individual familiarity with the ravages of SARS-CoV-2. Some will remain largely unscathed by illness, many will feel the economic pinch of societal lockdowns, many will also lose friends or loved ones to the virus, others will succumb to it themselves. No one will emerge unchanged.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

—The territory now covered by Erving was settled about 1801, by Col.

Asaph White, of Heath, who built a log house in the wilderness.

The Territory Now Covered

A granite nothing, a name only, a scratched-up pile

of planet, tarped with old snow.

Every track it seemed

was days old, glassed by the sun and useless, though

there was no sun today.

Any movement

would have cracked something, a leaf, a pane of ice—thrown

out some flare,

some sound, but I heard

nothing.

My mind

was a gully of rock

sluiced with rock. It was a field of weeds overgrown now

with weeds. The deer

seemed simply to exist in another world.

I followed lines which came together

and split apart in trunks

and trails, I followed lines which were at every moment

the best way through the world. I begged

for notice, I paced the edge of a sea.

Dark piles under hemlocks

where snow was thin. Hoof-scrapes

for the infants of oak.

I sat on a fallen tree to take my meal of salt bread, unlacing

my boot to find the foot

that had been bothering the stone

by David Troupes

from The Ecotheo Review

Michael Pollan on The Sickness in Our Food Supply

Michael Pollan in the New York Review of Books:

“Only when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett observed, “do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For our society, the Covid-19 pandemic represents an ebb tide of historic proportions, one that is laying bare vulnerabilities and inequities that in normal times have gone undiscovered. Nowhere is this more evident than in the American food system. A series of shocks has exposed weak links in our food chain that threaten to leave grocery shelves as patchy and unpredictable as those in the former Soviet bloc. The very system that made possible the bounty of the American supermarket—its vaunted efficiency and ability to “pile it high and sell it cheap”—suddenly seems questionable, if not misguided. But the problems the novel coronavirus has revealed are not limited to the way we produce and distribute food. They also show up on our plates, since the diet on offer at the end of the industrial food chain is linked to precisely the types of chronic disease that render us more vulnerable to Covid-19.

“Only when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett observed, “do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For our society, the Covid-19 pandemic represents an ebb tide of historic proportions, one that is laying bare vulnerabilities and inequities that in normal times have gone undiscovered. Nowhere is this more evident than in the American food system. A series of shocks has exposed weak links in our food chain that threaten to leave grocery shelves as patchy and unpredictable as those in the former Soviet bloc. The very system that made possible the bounty of the American supermarket—its vaunted efficiency and ability to “pile it high and sell it cheap”—suddenly seems questionable, if not misguided. But the problems the novel coronavirus has revealed are not limited to the way we produce and distribute food. They also show up on our plates, since the diet on offer at the end of the industrial food chain is linked to precisely the types of chronic disease that render us more vulnerable to Covid-19.

The juxtaposition of images in the news of farmers destroying crops and dumping milk with empty supermarket shelves or hungry Americans lining up for hours at food banks tells a story of economic efficiency gone mad. Today the US actually has two separate food chains, each supplying roughly half of the market. The retail food chain links one set of farmers to grocery stores, and a second chain links a different set of farmers to institutional purchasers of food, such as restaurants, schools, and corporate offices. With the shutting down of much of the economy, as Americans stay home, this second food chain has essentially collapsed. But because of the way the industry has developed over the past several decades, it’s virtually impossible to reroute food normally sold in bulk to institutions to the retail outlets now clamoring for it. There’s still plenty of food coming from American farms, but no easy way to get it where it’s needed.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: John Danaher on Our Coming Automated Utopia

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Humans build machines, in part, to relieve themselves from the burden of work on difficult, repetitive tasks. And yet, despite the fact that machines are everywhere, most of us are still working pretty hard. But maybe that’s about to change. Futurists like John Danaher believe that society is finally on the brink of making a transition to a world in which work would be optional, rather than mandatory — and he thinks that’s a very good thing. It will take some adjusting, personally as well as economically, but he envisions a future in which human creativity and artistic impulse can flourish in a world free of the demands of working for a living. We talk about what that would entail, whether it’s realistic, and what comes next.

Humans build machines, in part, to relieve themselves from the burden of work on difficult, repetitive tasks. And yet, despite the fact that machines are everywhere, most of us are still working pretty hard. But maybe that’s about to change. Futurists like John Danaher believe that society is finally on the brink of making a transition to a world in which work would be optional, rather than mandatory — and he thinks that’s a very good thing. It will take some adjusting, personally as well as economically, but he envisions a future in which human creativity and artistic impulse can flourish in a world free of the demands of working for a living. We talk about what that would entail, whether it’s realistic, and what comes next.

More here.

Coronavirus Won’t Kill Globalization But It Will Look Different After the Pandemic

Arjun Appadurai in Time:

Even in the heady early years of globalization back in the 1990s, scholars of the new trend were worried about its viral qualities: its speed, its ability to penetrate borders and regulations, its capacity to transform and even colonize the countries to which it came. I was one of these analysts. Though most of us thought globalization would likely be a largely positive force, we did not anticipate then that globalization could gradually become dangerous, infectious and hard to control.

Then came a spate of viruses that themselves seemed to be global travelers: HIV, the swine flu, mad cow disease, SARS, various brands of influenza, and now COVID-19. This last scourge is the most globalized in our history. Its speed of movement is matched only by the scale of its global reach. And it has unleashed an assault against globalization, with critics using the current pandemic as an example of how it can go wrong.

All of a sudden, many in media, academia and politics seem ready to hit the pause button on globalization. “Globalization is headed to the ICU,”a Foreign Policy column argued on March 9, while The Economist’s May 14 issue asked whether COVID-19 had killed globalization.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: Understanding Quantum Mechanics, Parts 1 & 2

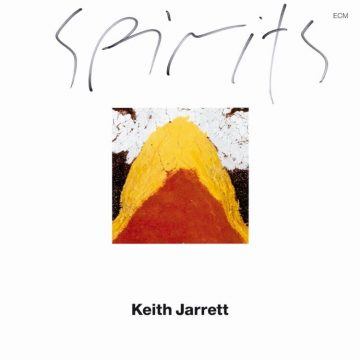

Keith Jarrett – Tokyo Solo 2002 Encores

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eqr0ZmgmDr4

Keith Jarrett and Digital Culture

Chase Kuesel at Music and Literature:

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation.

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation.

As the audience stood and complied, Jarrett finally appeared, flanked once again by his longtime trio-mates Gary Peacock on bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums. The atmosphere of camaraderie did not last long, as Jarrett examined the audience for just a few seconds before hastily declaring, “See you later” and walking offstage. There was momentary confusion: surely this could not be a repeat of the 2007 performance, where Jarrett issued his diatribe against the audience before even playing a note. But there was Stephen Cloud, Jarrett’s manager, walking on stage to beg for appropriate behavior once again: apparently Jarrett had seen some people in the audience flashing their cameras.

more here.

The Politics of Humiliation: A Modern History

Thomas W Laqeur at Literary Review:

No emotion stands nearer to the foundational myths of the human social order than shame. In the beginning, Adam and Eve stood together ‘both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed’. And then they ate of the tree of knowledge; their eyes opened; they knew they were naked; they covered themselves with fig leaves. Their shame was what told God they had fallen and become humans of our sort. Protagoras tells Socrates that after Prometheus had distinguished humans from other animals by giving them fire, Zeus gave them both shame and justice so that they could live together in harmony.

No emotion stands nearer to the foundational myths of the human social order than shame. In the beginning, Adam and Eve stood together ‘both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed’. And then they ate of the tree of knowledge; their eyes opened; they knew they were naked; they covered themselves with fig leaves. Their shame was what told God they had fallen and become humans of our sort. Protagoras tells Socrates that after Prometheus had distinguished humans from other animals by giving them fire, Zeus gave them both shame and justice so that they could live together in harmony.

Shame is the emotion that signals to us that we have done something wrong or dishonourable; it is also what leaves us vulnerable to being made to feel dishonoured, degraded, disgraced or ashamed by the actions of others – that is, to be humiliated.

more here.

Gatsbys of Our Time

Matt Hanson in The Baffler:

IN A TELEGRAM SENT from the South of France in March of 1925 to the Scribner office in New York, F. Scott Fitzgerald shouted the new inspiration for his third novel from across the Atlantic: “CRAZY ABOUT TITLE UNDER THE RED WHITE AND BLUE STOP WHART WOULD DELAY BE.” Luckily, his publisher was either too busy printing The Great Gatsby to make any changes or was too tactful to tell the excitable author he had a dumb idea. The phrase works better as the title for a new study of the novel’s legacy by renowned cultural critic Greil Marcus. The Great Gatsby lives on almost a century after its anticlimactic publication, Marcus argues, because it works as both a symbol of and a critique of different aspects of the American Dream—patriotism, wealth, disenchantment, the pursuit of happiness.

IN A TELEGRAM SENT from the South of France in March of 1925 to the Scribner office in New York, F. Scott Fitzgerald shouted the new inspiration for his third novel from across the Atlantic: “CRAZY ABOUT TITLE UNDER THE RED WHITE AND BLUE STOP WHART WOULD DELAY BE.” Luckily, his publisher was either too busy printing The Great Gatsby to make any changes or was too tactful to tell the excitable author he had a dumb idea. The phrase works better as the title for a new study of the novel’s legacy by renowned cultural critic Greil Marcus. The Great Gatsby lives on almost a century after its anticlimactic publication, Marcus argues, because it works as both a symbol of and a critique of different aspects of the American Dream—patriotism, wealth, disenchantment, the pursuit of happiness.

In Under the Red White and Blue, Marcus dusts off a collection of cultural products and finds Gatsby’s fingerprints all over them. He finds traces of Gatsby (sometimes more convincingly than others) in songs by Lana Del Rey and Jelly Roll Morton; in novels by Chandler, Roth, and Ross Macdonald; in an epic stage play that features a live reading of the entire text; in one of Andy Kaufman’s standup routines; and, of course, in the book’s various film adaptations. Marcus gets more out of director Baz Luhrmann’s flashy 2013 version than it probably deserves—that one was the fourth attempt, not counting the 1926 silent movie version, and like the others it fell short of its potential. Gatsby is also invoked in the nicknames of Korean pop stars and in advertisements for swanky New York luxury hotels that offer “the full Gatsby experience,” blood-stained swimming pools not included.

More here.

What do our dreams mean?

Cath Pound in BBC:

Dreams have fascinated philosophers and artists for centuries. They have been seen as divine messages, a way of unleashing creativity and, since the advent of psychoanalysis in the 19th Century, the key to understanding our unconscious. As so many of us have been experiencing unusually vivid dreams in recent weeks, it seems an opportune moment to explore the way in which they have been understood and depicted throughout the centuries. In doing so we may even find some intriguing parallels with our own experiences. But why are we dreaming so vividly now? “We’re in a new situation so there’s new emotions to process,” says psychotherapist Philippa Perry, who was inundated with replies when she recently asked her followers to send her their dreams on Twitter. We make up narratives to make sense of those feelings that in dream manifest themselves “not straightforwardly but in metaphors”, she explains.

Dreams have fascinated philosophers and artists for centuries. They have been seen as divine messages, a way of unleashing creativity and, since the advent of psychoanalysis in the 19th Century, the key to understanding our unconscious. As so many of us have been experiencing unusually vivid dreams in recent weeks, it seems an opportune moment to explore the way in which they have been understood and depicted throughout the centuries. In doing so we may even find some intriguing parallels with our own experiences. But why are we dreaming so vividly now? “We’re in a new situation so there’s new emotions to process,” says psychotherapist Philippa Perry, who was inundated with replies when she recently asked her followers to send her their dreams on Twitter. We make up narratives to make sense of those feelings that in dream manifest themselves “not straightforwardly but in metaphors”, she explains.

Albrecht Dürer’s Dream Vision (1525) is the first known depiction in Western art of an artist’s personal dream. The watercolour, seemingly hastily produced on waking, shows a deluge of water descending from the sky to engulf him. “I awoke trembling in every limb and it took a long time for me to recover,” he noted. Perry says that although her training taught her there was no such thing as a dream dictionary, decades of practice have shown her that “certain objects usually stand for a certain thing”, and “if somebody dreams about water that is usually about feelings”. To her, it sounds as if Dürer was “drowning in feelings”, and although of course she cannot be sure what those feelings were, “most of us, whether we admit it or not, or are ignorant of it when awake, fear annihilation and oblivion”, she says. Perhaps it is unsurprising that many of the dreams Perry was sent on Twitter also involved people being engulfed with water, although the woman who dreamt she was surfing on a tsunami was clearly dealing with her emotions better than Dürer.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Sherbet

The problem here is that

This isn’t pretty, the

Sort of thing that

Can easily be dealt with

With words. After

All it’s

A horror story to sit,

A black man with

A white wife in

The middle of a hot

Sunday afternoon in

The Jefferson Hotel in

Richmond, Va., and wait

Like a criminal for service

From a young white waitress

Who has decided that

This looks like something

She doesn’t want

To be a part of. What poetry

Could describe the

Perfect angle of

This woman’s back as

She walks, just so,

Mapping the room off

On War and Sports Metaphors for Argument

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

The vocabularies of sports and war feel natural for describing arguments and their performances. From battle, we describe arguments as swords, as they may have a thrust, may cut both ways, and may be parried. A case, further, can be a full-frontal assault, and we may rush once more unto the breach. There are defensive positions and rear-guard actions. One’s best arguments are one’s heavy artillery, and one may lay siege to viewpoints. And one may, on the sports model, score points or score own goals with successful or unsuccessful arguments, respectively. One may play soft- or hardball. Powerful arguments are slam dunks or home runs, and good rebuttals are counterattacks. Or one may change the subject with a punt. There’s no doubt that our vocabulary for describing what happens when we argue is thick with this metaphorical idiom. The question is whether it is a good thing or not – does the vocabulary of adversarial contest distort our relationship with argument? We hold it need not, but there are some concerns that must be addressed.

The first concern is that sport and war metaphors are misplaced because they presuppose (and seem to endorse) hostility between arguers, and this hostility has objectionable consequences. One’s objective in a game and in a war is to win, to defeat the adversary. As the saying goes, all is fair in love and war, so (leaving love aside) when we turn to the context of argumentation, the metaphors make it difficult to see what would be wrong with using all available means to win in argument. However, unlike in a war, successful argument depends upon arguers following the rules. Further, when one loses an argument, one nevertheless learns something about one’s views. And one may change one’s mind for the better. Losing an argument can be beneficial to the loser. The war and sport metaphors, so the objection goes, fail to recognize this complex of features of argument; for that reason, they are inapt. Read more »