Dr. Larry Norton, a breast oncologist, is well-known as a leader in the development of drug treatments for breast cancer. His research has established the importance of using sequential combinations of drugs — a strategy aimed to overcome different drug sensitivities among the cells in a tumor. He has served in leadership positions in several national cancer-related organizations, including serving as president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in 2001-2002, and is chairman of the board of directors of the ASCO Foundation. Currently, Dr. Norton is serving as the Senior Vice President at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a Professor of Medicine at Weill-Cornell Medical College with over 350 published articles and book chapters to his name.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now?

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now? In the summer of 2016, James and Becca Reed, a lower-income couple living in Austin, Texas, decided it was time to save their lives. The Reeds, married more than twenty-five years, had become morbidly obese, diabetic, and depressed. They were taking a combined thirty-two medications. Only in their early fifties, they had arrived at this condition via a well-trod path: They ate their way into it. They did no more than consume what the American food industry not only offers in abundance—salt, starch, and sweetness—but also encourages us to eat.

In the summer of 2016, James and Becca Reed, a lower-income couple living in Austin, Texas, decided it was time to save their lives. The Reeds, married more than twenty-five years, had become morbidly obese, diabetic, and depressed. They were taking a combined thirty-two medications. Only in their early fifties, they had arrived at this condition via a well-trod path: They ate their way into it. They did no more than consume what the American food industry not only offers in abundance—salt, starch, and sweetness—but also encourages us to eat. We haven’t talked about the socialization of intelligence very much. We talked a lot about intelligence as being individual human things, yet the thing that distinguishes humans from other animals is our possession of human language, which allows us both to think and communicate in ways that other animals don’t appear to be able to. This gives us a cooperative power as a global organism, which is causing lots of trouble. If I were another species, I’d be pretty damn pissed off right now. What makes human beings effective is not their individual intelligences, though there are many very intelligent people in this room, but their communal intelligence.

We haven’t talked about the socialization of intelligence very much. We talked a lot about intelligence as being individual human things, yet the thing that distinguishes humans from other animals is our possession of human language, which allows us both to think and communicate in ways that other animals don’t appear to be able to. This gives us a cooperative power as a global organism, which is causing lots of trouble. If I were another species, I’d be pretty damn pissed off right now. What makes human beings effective is not their individual intelligences, though there are many very intelligent people in this room, but their communal intelligence. To consider yourself well versed in contemporary literature without reading short stories is to visit the Eiffel Tower and say you’ve seen Europe. Not only would monumental writers be missing from your literary tour, but entire angles and moves and structures of which the novel, in its bulk, is incapable. The quirky neighborhood, the narrow cobblestone alley, the stray cats and small museums and the store that sells only butter.

To consider yourself well versed in contemporary literature without reading short stories is to visit the Eiffel Tower and say you’ve seen Europe. Not only would monumental writers be missing from your literary tour, but entire angles and moves and structures of which the novel, in its bulk, is incapable. The quirky neighborhood, the narrow cobblestone alley, the stray cats and small museums and the store that sells only butter. In the Oval Office, an annoyed President Trump ended an argument he was having with his aides. He reached into a drawer, took out his iPhone and threw it on top of the historic Resolute Desk:

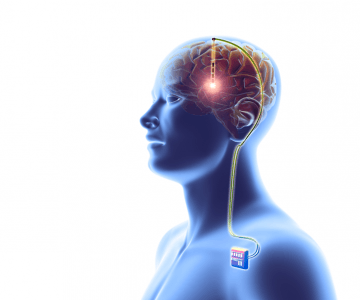

In the Oval Office, an annoyed President Trump ended an argument he was having with his aides. He reached into a drawer, took out his iPhone and threw it on top of the historic Resolute Desk: It is a good question, but I was a little surprised to see it as the title of a research paper in a medical journal: “How Happy Is Too Happy?” Yet there it was in a publication from 2012. The article was written by two Germans and an American, and they were grappling with the issue of how we should deal with the possibility of manipulating people’s moods and feeling of happiness through brain stimulation. If you have direct access to the reward system and can turn the feeling of euphoria up or down, who decides what the level should be? The doctors or the person whose brain is on the line?

It is a good question, but I was a little surprised to see it as the title of a research paper in a medical journal: “How Happy Is Too Happy?” Yet there it was in a publication from 2012. The article was written by two Germans and an American, and they were grappling with the issue of how we should deal with the possibility of manipulating people’s moods and feeling of happiness through brain stimulation. If you have direct access to the reward system and can turn the feeling of euphoria up or down, who decides what the level should be? The doctors or the person whose brain is on the line? I

I