Taku Yamanaka in Nature:

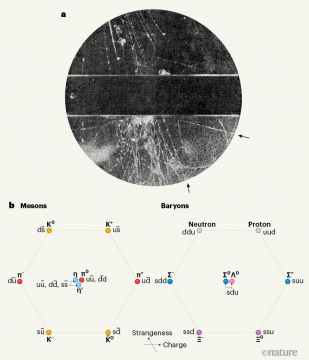

In the late 1940s, the physicists George Rochester and Clifford Butler1 observed something unusual in their charged-particle detector. They were studying the interactions between high-energy cosmic rays and a lead plate in the detector when they spotted V-shaped particle tracks (Fig. 1a). The small gap between the lead plate and the vertex of the tracks indicated that an invisible neutral particle had been produced in the plate, had travelled for a short distance and had then decayed into two visible charged particles. The mass of the neutral particle was about 1,000 times that of an electron, implying that it must be a previously unreported type of particle. This discovery paved the way for many puzzles and surprises in particle physics in the decades that followed.

In the late 1940s, the physicists George Rochester and Clifford Butler1 observed something unusual in their charged-particle detector. They were studying the interactions between high-energy cosmic rays and a lead plate in the detector when they spotted V-shaped particle tracks (Fig. 1a). The small gap between the lead plate and the vertex of the tracks indicated that an invisible neutral particle had been produced in the plate, had travelled for a short distance and had then decayed into two visible charged particles. The mass of the neutral particle was about 1,000 times that of an electron, implying that it must be a previously unreported type of particle. This discovery paved the way for many puzzles and surprises in particle physics in the decades that followed.

At the time of Rochester and Butler’s work, protons, neutrons, electrons and particles called pions (short for π mesons) had been identified, and were known to be sufficient to form atoms. Pions were proposed2 in 1935 to explain how protons and neutrons are held together in small atomic nuclei by the strong nuclear force, and were found experimentally3,4 in 1947. While searching for a pion in cosmic rays, scientists discovered a different particle5, which is now called a muon. A heavy charged particle was then found6 in 1944, followed by Rochester and Butler’s unstable neutral particle. But the discovery of unexpected particles did not stop there. Then came the τ meson, which decays into three pions; the θ meson, decaying into two pions; the κ meson, decaying into a muon and an invisible particle; the Λ0 particle, decaying into a proton and a pion; and the list goes on.

More here.