Month: October 2019

This Is What Terror Sounds Like

Sudip Bose at The American Scholar:

I cannot think of a contemporary piece that has attracted as much of a cult following as Haas’s mesmerizing, disorienting, and utterly moving in vain. It begins with a swirl of sound in which the cascading runs suggest a sense of falling, yet as these lines rise in pitch, there’s a feeling of upward motion, too—the musical equivalent, as many commentators have noted, of M. C. Escher’s staircase, descending and ascending all at once. Soon after a hair-raising crescendo, the listener is plunged into another realm, in which microtonality seems at war with conventional tuning. The sounds pulse like flashes of light through an abiding darkness, which is not only metaphorical but also literal, for in a live performance, the house lights gradually dim and are then cut. (Unable to see either their music stands or the conductor, the performers must play extended sequences of very complex music from memory.) Out of this darkness, a new world of sound emerges, something elemental—familiar but strange—with the textures and harmonies undergoing subtle transformations. Just when it seems as if some redemptive moment will arrive, the music becomes frustratingly dizzying once again. Indeed, listening to in vain can feel like being trapped in an anxiety dream from which you almost manage to escape, but ultimately cannot.

I cannot think of a contemporary piece that has attracted as much of a cult following as Haas’s mesmerizing, disorienting, and utterly moving in vain. It begins with a swirl of sound in which the cascading runs suggest a sense of falling, yet as these lines rise in pitch, there’s a feeling of upward motion, too—the musical equivalent, as many commentators have noted, of M. C. Escher’s staircase, descending and ascending all at once. Soon after a hair-raising crescendo, the listener is plunged into another realm, in which microtonality seems at war with conventional tuning. The sounds pulse like flashes of light through an abiding darkness, which is not only metaphorical but also literal, for in a live performance, the house lights gradually dim and are then cut. (Unable to see either their music stands or the conductor, the performers must play extended sequences of very complex music from memory.) Out of this darkness, a new world of sound emerges, something elemental—familiar but strange—with the textures and harmonies undergoing subtle transformations. Just when it seems as if some redemptive moment will arrive, the music becomes frustratingly dizzying once again. Indeed, listening to in vain can feel like being trapped in an anxiety dream from which you almost manage to escape, but ultimately cannot.

more here.

The Horse Painter

Michael Prodger at The New Statesman:

Stubbs was, however, an interpreter as well as an observer. His pictures reveal his fascination with relationships; between owners and their horses and hounds, between servants and masters, between animals themselves. And they show his very modern conviction that animals have emotions similar to and every bit as potent as our own. The eyes of his creatures are full of feeling and frequently stare back at the viewer with disconcerting intensity. You need only to look at the eye of his horse being devoured by a lion, a motif he returned to again and again, to be made uncomfortable as a witness to its agony. In a remarkable late work of 1800 showing the Earl of Clarendon’s gamekeeper with his dog about to dispatch a doe, man and doomed animal look out of the painting, making the viewer complicit in the coup de grâce. Other near contemporaries such as James Ward and Théodore Géricault gave their animals emotions, but without the same fellow feeling.

Stubbs was, however, an interpreter as well as an observer. His pictures reveal his fascination with relationships; between owners and their horses and hounds, between servants and masters, between animals themselves. And they show his very modern conviction that animals have emotions similar to and every bit as potent as our own. The eyes of his creatures are full of feeling and frequently stare back at the viewer with disconcerting intensity. You need only to look at the eye of his horse being devoured by a lion, a motif he returned to again and again, to be made uncomfortable as a witness to its agony. In a remarkable late work of 1800 showing the Earl of Clarendon’s gamekeeper with his dog about to dispatch a doe, man and doomed animal look out of the painting, making the viewer complicit in the coup de grâce. Other near contemporaries such as James Ward and Théodore Géricault gave their animals emotions, but without the same fellow feeling.

more here.

The Oddly Soothing Apocalypses of László Krasznahorkai

David Schurman Wallace at The Baffler:

Krasznahorkai is a perplexing figure in today’s literary landscape: he is, in internet parlance, committed to his bit. The Hungarian author cultivates an air of mystery (he “lives in reclusiveness,” according to one biographical note) and has been known to give cryptic answers in his occasional interviews (“Wherever I happen to disappear, it is neither into silence nor into darkness,” he told Asymptote Journal). A literary heir to Kafka, Beckett, and Dostoyevsky, for him the existence of God and the nature of infinity are subjects that are not too large. Krasznahorkai is known for long, labyrinthine sentences that painstakingly excavate every fleck of a subject’s consciousness, rolling across multiple pages with precious little white space. In the tradition of Mallarmé, he has said that he always wanted to write one unified book, and Wenckheim, reportedly the author’s last, seeks to tie together three previous novels: Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, and War & War, unifying them into one great work. Accordingly, Wenckheim takes up the ideas of these earlier books and enlarges them: the absurd is more absurd, the incomprehensible more incomprehensible than ever.

Krasznahorkai is a perplexing figure in today’s literary landscape: he is, in internet parlance, committed to his bit. The Hungarian author cultivates an air of mystery (he “lives in reclusiveness,” according to one biographical note) and has been known to give cryptic answers in his occasional interviews (“Wherever I happen to disappear, it is neither into silence nor into darkness,” he told Asymptote Journal). A literary heir to Kafka, Beckett, and Dostoyevsky, for him the existence of God and the nature of infinity are subjects that are not too large. Krasznahorkai is known for long, labyrinthine sentences that painstakingly excavate every fleck of a subject’s consciousness, rolling across multiple pages with precious little white space. In the tradition of Mallarmé, he has said that he always wanted to write one unified book, and Wenckheim, reportedly the author’s last, seeks to tie together three previous novels: Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, and War & War, unifying them into one great work. Accordingly, Wenckheim takes up the ideas of these earlier books and enlarges them: the absurd is more absurd, the incomprehensible more incomprehensible than ever.

more here.

The Real Nature of Thomas Edison’s Genius

Casey Cep in The New Yorker:

There were ideas long before there were light bulbs. But, of all the ideas that have ever turned into inventions, only the light bulb became a symbol of ideas. Earlier innovations had literalized the experience of “seeing the light,” but no one went around talking about torchlight moments or sketching candles into cartoon thought bubbles. What made the light bulb such an irresistible image for ideas was not just the invention but its inventor.

There were ideas long before there were light bulbs. But, of all the ideas that have ever turned into inventions, only the light bulb became a symbol of ideas. Earlier innovations had literalized the experience of “seeing the light,” but no one went around talking about torchlight moments or sketching candles into cartoon thought bubbles. What made the light bulb such an irresistible image for ideas was not just the invention but its inventor.

Thomas Edison was already well known by the time he perfected the long-burning incandescent light bulb, but he was photographed next to one of them so often that the public came to associate the bulbs with invention itself. That made sense, by a kind of transitive property of ingenuity: during his lifetime, Edison patented a record-setting one thousand and ninety-three different inventions. On a single day in 1888, he wrote down a hundred and twelve ideas; averaged across his adult life, he patented something roughly every eleven days. There was the light bulb and the phonograph, of course, but also the kinetoscope, the dictating machine, the alkaline battery, and the electric meter. Plus: a sap extractor, a talking doll, the world’s largest rock crusher, an electric pen, a fruit preserver, and a tornado-proof house.

More here.

How life blossomed after the dinosaurs died

Elizabeth Pennisi in Science:

In 2014, when Ian Miller and Tyler Lyson first visited Corral Bluffs, a fossil site 100 kilometers south of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science where they work, Lyson was not impressed by the few vertebrate fossils he saw. But on a return trip later that year, he split open small boulders called concretions—and found dozens of skulls. Now, he, Miller, and their colleagues have combined the site’s trove of plant and animal fossils with a detailed chronology of the rock layers to tell a momentous story: how life recovered from the asteroid impact that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

In 2014, when Ian Miller and Tyler Lyson first visited Corral Bluffs, a fossil site 100 kilometers south of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science where they work, Lyson was not impressed by the few vertebrate fossils he saw. But on a return trip later that year, he split open small boulders called concretions—and found dozens of skulls. Now, he, Miller, and their colleagues have combined the site’s trove of plant and animal fossils with a detailed chronology of the rock layers to tell a momentous story: how life recovered from the asteroid impact that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

Plants and animals came back much faster than thought, with plants spurring mammals to diversify, the team reports today in Science. “They get almost the whole picture, which is quite exciting,” says functional anatomist Amy Chew of Brown University. “This high-resolution integrated record really tells us what’s going on.” When the asteroid slammed into Earth, it wiped out 75% of living species, including any mammal much larger than a rat. Half the plant species died out. With the great dinosaurs gone, mammals expanded, and the new study traces that process in exquisite detail. Most fossil sites from after the impact have gaps, but sediment accumulated nearly continuously for 1 million years on the flood plain that is now the Corral Bluffs site. So the site preserves a full record of ancient life and the environment.

Such sites can be hard to date. But Miller, a paleobotanist, and his colleagues collected 37,000 grains of pollen and spores, which revealed a clear marker of the asteroid impact: a surge in the growth of ferns, which thrive in disturbed environments.

More here.

Friday Poem

Magnitude and Bond

More than anything, I need this boy

so close to my ears, his questions

electric as honeybees in an acreage

of goldenrod and aster. And time where

we are, slow sugar in the veins

of white pine, rubbery mushrooms

cloistered at their feet. His tawny

listening at the water’s edge, shy

antlers in pooling green light, while

we consider fox prints etched in clay.

I need little black boys to be able to be

little black boys, whole salt water galaxies

in cotton and loudness—not fixed

in stunned suspension, episodes on hot

asphalt, waiting in the dazzling absence

of apology. I need this kid to stay mighty

and coltish, thundering alongside

other black kids, their wrestle and whoop,

the brightness of it—I need for the world

to bear it. And until it will, may the trees

kneel closer, while we sit in mineral hush,

together. May the boy whose dark eyes

are an echo of my father’s dark eyes,

and his father’s dark eyes, reach

with cupped hands into the braided

current. The boy, restless and lanky, the boy

for whom each moment endlessly opens,

for the attention he invests in the beetle’s

lacquered armor, each furrowed seed

or heartbeat, the boy who once told me

the world gives you second chances, the boy

tugging my arm, saying look, saying now.

by Terez Dutton

from the Academy of American Poets, 2019

The Humanitarian Crisis of Deaths of Despair

David V. Johnson in the APA Blog:

Last April, Princeton University economists and married partners Anne Case and Sir Angus Deaton delivered the Tanner Lectures on Human Values at Stanford University. The title of their talks, “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” is also the provisional name of their forthcoming book, to be published in 2020.

Last April, Princeton University economists and married partners Anne Case and Sir Angus Deaton delivered the Tanner Lectures on Human Values at Stanford University. The title of their talks, “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” is also the provisional name of their forthcoming book, to be published in 2020.

The couple’s research has focused on disturbing mortality data for a specific demographic: white non-Hispanic Americans without college degrees. This century, they have been dying at alarming rates from what Case and Deaton call “deaths of despair,” which cover suicide, alcohol-related disease, and drug overdoses (primarily driven by opioids). These deaths have, along with US obesity, heart disease, and cancer rates, contributed to a shocking recent decline in US life expectancy for three straight years—something which hasn’t happened since World War I and the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. The rates for “deaths of despair” are not as high for college-educated whites or for other racial minorities, and there are many potential economic and sociological reasons for this.

Case and Deaton’s research raises important questions for the US political economy and the legacy of neoliberalism. But I am more interested in the framing of the mortality statistics as “deaths of despair.”

More here.

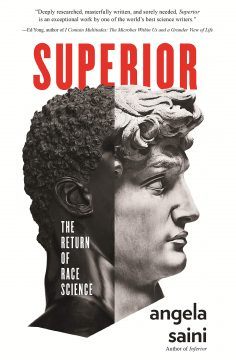

The insidious effects of scientific investigations into race

John Horgan in Scientific American:

A dozen years ago I flew to Europe to speak at a conference on science’s limits. The meeting’s organizer greeted me with a tirade about James Watson, co-discoverer of the double helix, who had just stated publicly that blacks are less intelligent than whites. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours,” Watson told a journalist, “whereas all the testing says not really.”

A dozen years ago I flew to Europe to speak at a conference on science’s limits. The meeting’s organizer greeted me with a tirade about James Watson, co-discoverer of the double helix, who had just stated publicly that blacks are less intelligent than whites. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours,” Watson told a journalist, “whereas all the testing says not really.”

At first I thought my host, a world-famous intellectual whose work I admired, was condemning Watson. But no, he was condemning Watson’s critics, whom he saw as cowards attacking a courageous truth-teller. I wish I could say I was shocked by my host’s rant, but I have had many encounters like this over the decades. Just as scientists and other intellectuals often reveal in private that they believe in the paranormal, so many disclose that they believe in the innate inferiority of certain groups.

That 2007 incident came back to me as I read Superior: The Return of Race Science by British journalist Angela Saini (who is coming to my school Nov. 4, see Postscript). Superior is a thoroughly researched, brilliantly written and deeply disturbing book.

More here.

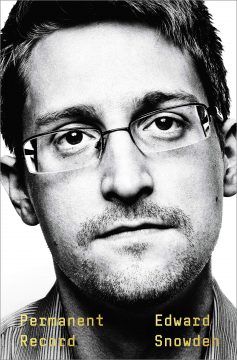

Snowden in the Labyrinth

Jonathan Lethem in the New York Review of Books:

Edward Snowden, late in the pages of his memoir, Permanent Record, describes his sensation at being personally introduced to XKEYSCORE, the NSA’s ultimate tool of intimate, individual electronic surveillance. Among the NSA’s technological tools (some of which Snowden aided in perfecting), XKEYSCORE was, according to Snowden, “the most invasive…if only because [the NSA agents are] closest to the user—that is, the closest to the person being surveilled.” For nearly three hundred pages, the memoir has built to this scene, foreshadowed in the preface, in which the whistleblower-in-the-making sees behind the curtain:

Edward Snowden, late in the pages of his memoir, Permanent Record, describes his sensation at being personally introduced to XKEYSCORE, the NSA’s ultimate tool of intimate, individual electronic surveillance. Among the NSA’s technological tools (some of which Snowden aided in perfecting), XKEYSCORE was, according to Snowden, “the most invasive…if only because [the NSA agents are] closest to the user—that is, the closest to the person being surveilled.” For nearly three hundred pages, the memoir has built to this scene, foreshadowed in the preface, in which the whistleblower-in-the-making sees behind the curtain:

I sat at a terminal from which I had practically unlimited access to the communications of nearly every man, woman, and child on earth who’d ever dialed a phone or touched a computer. Among those people were about 320 million of my fellow American citizens, who in the regular conduct of their everyday lives were being surveilled in gross contravention of not just the Constitution of the United States, but the basic values of any free society.

The steady approach to Snowden’s come-to-Jesus encounter with XKEYSCORE is as meticulous as the incremental unveiling of the terror of Cthulhu in an H.P. Lovecraft tale.

More here.

Azra Raza In Conversation With Siddhartha Mukherjee at the Asia Society in NYC

For Smoking

Susanna Kaysen at n+1:

What is smoking for? People who don’t smoke think it’s for feeding an addiction, and they’re right. Once you’ve started smoking, it’s hard to stop. But that’s a narrow definition. There’s a physical addiction and there’s also a spiritual addiction. Perhaps you could call it a metaphysical addiction.

What is smoking for? People who don’t smoke think it’s for feeding an addiction, and they’re right. Once you’ve started smoking, it’s hard to stop. But that’s a narrow definition. There’s a physical addiction and there’s also a spiritual addiction. Perhaps you could call it a metaphysical addiction.

To have a cigarette is to step out of day-to-day existence and into a private, solitary existence. It’s just you and your cigarette. Hello, says the cigarette, You’ve come to visit me. And you say, Yes, hello—but really, you know that you’ve come to visit yourself. The cigarette is a method of being alone and listening to yourself, of having nobody but yourself to listen to or to be with.

It’s also a way to stop time. Time spent smoking is not real time. Nothing else is happening. There is no progress. There is no trying to start something or complete something or even forget something.

Since smokers have been excommunicated from indoor life, this contemplative aspect of smoking has come to the fore.

more here.

The Disputed Heroism of Edward Snowden

Alan Rusbridger at the TLS:

Apart from his short video outing himself in 2013, Snowden has tended to keep himself out of the public eye, preferring that the material speak for itself. He is, in many respects, the opposite of Julian Assange – a figure with whom he is often bracketed. The founder of WikiLeaks wanted to be a player: impresario, editor, publisher, activist, leaker, information anarchist and troublemaker. Snowden, by contrast, simply wanted to get his documents into the hands of journalists, and to leave them to make the choices about what to publish.

Apart from his short video outing himself in 2013, Snowden has tended to keep himself out of the public eye, preferring that the material speak for itself. He is, in many respects, the opposite of Julian Assange – a figure with whom he is often bracketed. The founder of WikiLeaks wanted to be a player: impresario, editor, publisher, activist, leaker, information anarchist and troublemaker. Snowden, by contrast, simply wanted to get his documents into the hands of journalists, and to leave them to make the choices about what to publish.

Given his past reticence, this book is a surprisingly personal autobiography as well as a primer on the way modern states now operate in the digital sphere. Snowden lifts the veil on his family and upbringing (his mother worked for the NSA), and writes of his early fascination with computers, which began at the age of six when his parents – both of whom had top secret security clearances – gave him a Nintendo.

more here.

Renaissance Nun’s ‘Last Supper’ Painting Makes Public Debut After 450 Years in Hiding

Meilan Solly in Smithsonian:

Around 1568, Florentine nun Plautilla Nelli—a self-taught painter who ran an all-woman artists’ workshop out of her convent—embarked on her most ambitious project yet: a monumental Last Supper scene featuring life-size depictions of Jesus and the 12 Apostles.

Around 1568, Florentine nun Plautilla Nelli—a self-taught painter who ran an all-woman artists’ workshop out of her convent—embarked on her most ambitious project yet: a monumental Last Supper scene featuring life-size depictions of Jesus and the 12 Apostles.

As Alexandra Korey writes for the Florentine, Nelli’s roughly 21- by 6-and-a-half foot canvas is remarkable for its challenging composition, adept treatment of anatomy at a time when women were banned from studying the scientific field, and chosen subject. During the Renaissance, the majority of individuals who painted the biblical scene were male artists at the pinnacle of their careers. Per the nonprofit Advancing Women Artists organization, which restores and exhibits works by Florence’s female artists, Nelli’s masterpiece placed her among the ranks of such painters as Leonardo da Vinci, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Pietro Perugino, all of whom created versions of the Last Supper “to prove their prowess as art professionals.”

Despite boasting such a singular display of skill, the panel has long been overlooked. According to Visible: Plautilla Nelli and Her Last Supper Restored, a monograph edited by AWA Director Linda Falcone, Last Supper hung in the refectory (or dining hall) of the artist’s own convent, Santa Caterina, until the house of worship’s dissolution during the Napoleonic suppression of the early 19th century. The Florentine monastery of Santa Maria Novella acquired the painting in 1817, housing it in the refectory before moving it to a new location around 1865. In 1911, scholar Giovanna Pierattini reported, the portable panel was “removed from its stretcher, rolled up and moved to a warehouse, where it remained neglected for almost three decades.”

More here.

Beauty and Ugliness

Theodore Dalrymple in City Journal:

Simon draws attention to “the extreme ambivalence we now feel towards beauty both within and outside art,” and continues: “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish. Embarrassed by our yearning for beauty, we demean it as something tawdry, self-indulgent, or sentimental.”

Simon draws attention to “the extreme ambivalence we now feel towards beauty both within and outside art,” and continues: “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish. Embarrassed by our yearning for beauty, we demean it as something tawdry, self-indulgent, or sentimental.”

All that is necessary for ugliness to prosper is for artists to reject beauty.

Lenin abjured music, to which he was sensitive, because it made him feel well-disposed to the people around him, and he thought it would be necessary to kill so many of them. Theodor Adorno said that there could be no more poetry after Auschwitz. Our view of the world has become so politicized that we think that the unembarrassed celebration of beauty is a sign of insensibility to suffering and that exclusively to focus on the world’s deformations, its horrors, is in itself a sign of compassion. Reynolds was not tortured by such considerations.

More here.

My Adventures in Psychedelia

Helen Joyce in the New York Review of Books:

It all began with a book review. Last year, I read an article by David Aaronovitch in The Times of London about Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind. The book concerns a resurgence of interest in psychedelic drugs, which were widely banned after Timothy Leary’s antics with LSD, starting in the late 1960s, in which he encouraged American youth to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” In recent years, though, scientists have started to test therapeutic uses of psychedelics for an extraordinary range of ailments, including depression, addiction, and end-of-life angst.

It all began with a book review. Last year, I read an article by David Aaronovitch in The Times of London about Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind. The book concerns a resurgence of interest in psychedelic drugs, which were widely banned after Timothy Leary’s antics with LSD, starting in the late 1960s, in which he encouraged American youth to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” In recent years, though, scientists have started to test therapeutic uses of psychedelics for an extraordinary range of ailments, including depression, addiction, and end-of-life angst.

Aaronovitch mentioned in passing that he had been intrigued enough to book a “psychedelic retreat” in the Netherlands run by the British Psychedelic Society, though, in the event, his wife put her foot down and he canceled. To try psychedelics was something I’d secretly hankered after doing ever since I was a teenager, but I was always too cautious and risk-averse. As I got older, the moment seemed to pass. Today I am a middle-aged journalist working in London, the finance editor of The Economist, a wife, mother, and, to all appearances, a person totally devoid of countercultural tendencies.

And yet… on impulse, I arranged to go. Only after I booked did I tell my husband. He was bemused, but said it was fine by him, as long as I didn’t decide while I was under the influence that I didn’t love him anymore. My eighteen-year-old son thought the whole thing was hilarious (it turns out that your mother tripping is a good way to make drugs seem less cool).

More here.

John Preskill explains Quantum Supremacy

John Preskill in Quanta:

A recent paper from Google’s quantum computing lab announced that the company had achieved quantum supremacy. Everyone has been talking about it, but what does it all mean?

A recent paper from Google’s quantum computing lab announced that the company had achieved quantum supremacy. Everyone has been talking about it, but what does it all mean?

In 2012, I proposed the term “quantum supremacy” to describe the point where quantum computers can do things that classical computers can’t, regardless of whether those tasks are useful. With that new term, I wanted to emphasize that this is a privileged time in the history of our planet, when information technologies based on principles of quantum physics are ascendant.

The words “quantum supremacy” — if not the concept — proved to be controversial for two reasons. One is that supremacy, through its association with white supremacy, evokes a repugnant political stance. The other reason is that the word exacerbates the already overhyped reporting on the status of quantum technology. I anticipated the second objection, but failed to foresee the first. In any case, the term caught on, and it has been embraced with particular zeal by the Google AI Quantum team.

More here.

Life in China’s Surveillance State

John Lanchester in the London Review of Books:

The People’s Republic of China had its seventieth birthday on 1 October. ‘Sheng ri kuai le’ to the world’s biggest and most populous example of … of … well, actually, that sentence is hard to finish. There’s no off-the-shelf description for China’s political and economic system. ‘Socialism with Chinese characteristics’ is the Chinese Communist Party’s preferred term, but the s-word makes an odd fit with a country that is the world’s most important market for luxury goods, has the second largest number of billionaires, stages the world’s biggest one-day shopping event, ‘Singles’ Day’, and is home to the world’s biggest, fastest-expanding, spendiest, most materially aspirational middle class. Look at the UN’s Human Development Index: after seventy years of communist rule, China’s inequality figures are dramatically worse than those of the UK and even the US. Can we call that ‘socialism’?

The People’s Republic of China had its seventieth birthday on 1 October. ‘Sheng ri kuai le’ to the world’s biggest and most populous example of … of … well, actually, that sentence is hard to finish. There’s no off-the-shelf description for China’s political and economic system. ‘Socialism with Chinese characteristics’ is the Chinese Communist Party’s preferred term, but the s-word makes an odd fit with a country that is the world’s most important market for luxury goods, has the second largest number of billionaires, stages the world’s biggest one-day shopping event, ‘Singles’ Day’, and is home to the world’s biggest, fastest-expanding, spendiest, most materially aspirational middle class. Look at the UN’s Human Development Index: after seventy years of communist rule, China’s inequality figures are dramatically worse than those of the UK and even the US. Can we call that ‘socialism’?

It’s equally hard to claim China as a triumph of capitalism, given the completeness of state control over most areas of life and the extent of its open interventions in the national economy – capital controls, for instance, are a huge no-no in free-market economics, but are central to the way the CCP runs the biggest economy in the world. This system-with-no-name has been extraordinarily successful, with more than 800 million people raised out of absolute poverty since the 1980s. Growth hasn’t slowed down since the global financial crisis – or, as those cheeky scamps at the CCP tend to call it, the Western financial crisis. While the developed world has been struggling with low to no growth, China has grown by more than six per cent a year and a further eighty million mainly rural citizens have been raised out of absolute poverty since 2012. There is a strong claim that this scale of growth, sustained for such an unprecedented number of people over such a number of years, is the greatest economic achievement in human history.

More here.

Joseph DiGiovanna is shooting a 30 Year Timelapse of New York City

Carl Safina Is Certain Your Dog Loves You

Claudia Dryfus interviews Carl Safina at the NYT:

Among things, that they are capable of anticipation. For instance, they show much excitement when I simply touch my car keys, which might well signal that they are going to some place interesting, like the beach. That proves that they have imagination and even memory.

Among things, that they are capable of anticipation. For instance, they show much excitement when I simply touch my car keys, which might well signal that they are going to some place interesting, like the beach. That proves that they have imagination and even memory.

Another thing — and this shouldn’t surprise — they can be quite emotional. Some years ago, I lived with someone with a dog. Before we broke up, we argued a lot. Once, we took her dog to the beach and we started bickering there. That dog just basically collapsed into a pile of leaves and would not get up. She did not want to be with us! And we weren’t even yelling at her. She just did not want to be a part of an unhappy scene.

That showed me that they can have a real-time valuation of their experiences. They know what they prefer to avoid.

more here.