Portrait in Nightshade and Delayed Translation

In Saint Petersburg, on an autumn morning,

having been allowed an early entry

to the Hermitage, my family and I wandered

the empty hallways and corridors, virtually every space

adorned with famous paintings and artwork.

There must be a term for overloading on art.

One of Caravaggio’s boys smirked at us,

his lips a red that betrayed a sloppy kiss

recently delivered, while across the room

the Virgin looked on with nothing but sorrow.

Even in museums, the drama is staged.

Bored, I left my family and, steered myself,

foolish moth, toward the light coming

from a rotunda. Before me, the empty stairs.

Ready to descend, ready to step outside

into the damp and chilly air, I felt

the centuries-old reflex kick in, that sense

of being watched. When I turned, I found

no one; instead, I was staring at The Return

of the Prodigal Son. I had studied it, written about it

as a student. But no amount of study could have

prepared me for the size of it, the darkness of it.

There, the son knelt before his father, his dirty foot

left for inspection. Something broke. As clichéd

as it sounds, something inside me broke, and

as if captured on film, I found myself slowly sinking

to my knees. The tears began without warning until soon

I was sobbing. What reflex betrays one like this?

They come to New York City every week, in buses and trains and cars, carrying bags, carrying ambitions, carrying the fabulous clothes on their backs. They’re the fashion kids, the art kids, the theatre kids, the who-knows-what kids—creative renegades of nineteen or twenty or twenty-five. They’ve heard what we’ve all heard: that downtown is dead, that the rent is too damn high, that someone has paved paradise and put up a Duane Reade. Still, they keep coming, against all odds, tricked out in spangles, torn shirts, and tattoos, seeking a place where they can find themselves, and one another.

They come to New York City every week, in buses and trains and cars, carrying bags, carrying ambitions, carrying the fabulous clothes on their backs. They’re the fashion kids, the art kids, the theatre kids, the who-knows-what kids—creative renegades of nineteen or twenty or twenty-five. They’ve heard what we’ve all heard: that downtown is dead, that the rent is too damn high, that someone has paved paradise and put up a Duane Reade. Still, they keep coming, against all odds, tricked out in spangles, torn shirts, and tattoos, seeking a place where they can find themselves, and one another. Researchers may have found a way to improve a common treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by changing how the brain learns to respond less severely to fearful conditions, according to research published in Journal of Neuroscience. The study by researchers at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School suggests a potential improvement to exposure therapy—the current gold standard for PTSD treatment and anxiety reduction—which helps people gradually approach their trauma-related memories and feelings by confronting those memories in a safe setting, away from actual threat.

Researchers may have found a way to improve a common treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by changing how the brain learns to respond less severely to fearful conditions, according to research published in Journal of Neuroscience. The study by researchers at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School suggests a potential improvement to exposure therapy—the current gold standard for PTSD treatment and anxiety reduction—which helps people gradually approach their trauma-related memories and feelings by confronting those memories in a safe setting, away from actual threat. In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.)

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.) I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students.

I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students. “…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

“…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone:

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone: Abdullah, the delightful septuagenarian protagonist of Hussain M. Naqvi’s latest novel The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack, might be a ‘Cossack’ (having successfully imbibed his way to earning that name), but Naqvi himself is nothing short of a veritable Vaslav Nijinsky when it comes to negotiating the balletics of Pakistani Anglophone writing. Erudite yet entertaining, the Cossack’s story, in spite of his literally heavyweight frame and metaphorically heavyweight influence, gracefully pirouettes its way through the landscape of both Abdullah’s witty mind as well as the geographical terrain of Karachi in general, and Garden East in particular.

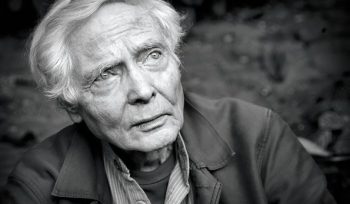

Abdullah, the delightful septuagenarian protagonist of Hussain M. Naqvi’s latest novel The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack, might be a ‘Cossack’ (having successfully imbibed his way to earning that name), but Naqvi himself is nothing short of a veritable Vaslav Nijinsky when it comes to negotiating the balletics of Pakistani Anglophone writing. Erudite yet entertaining, the Cossack’s story, in spite of his literally heavyweight frame and metaphorically heavyweight influence, gracefully pirouettes its way through the landscape of both Abdullah’s witty mind as well as the geographical terrain of Karachi in general, and Garden East in particular. As a student at Princeton, Merwin studied under John Berryman and R. P. Blackmur. After graduating in 1948, his travels would take him through Europe before he landed in the south of France. Michael Wiegers

As a student at Princeton, Merwin studied under John Berryman and R. P. Blackmur. After graduating in 1948, his travels would take him through Europe before he landed in the south of France. Michael Wiegers  When Laila Lalami’s 2014 novel The Moor’s Account was short-listed for a Pulitzer Prize, jurors called its tale of a 16th century Spanish expedition to Florida “compassionately imagined out of the gaps and silences of history.” Five years on, Lalami turns that same compassion to the silences of the present. In her timely fourth novel, The Other Americans, she follows an investigation into the death of an elderly Moroccan immigrant in an apparent hit-and-run and its impact on a California desert town.

When Laila Lalami’s 2014 novel The Moor’s Account was short-listed for a Pulitzer Prize, jurors called its tale of a 16th century Spanish expedition to Florida “compassionately imagined out of the gaps and silences of history.” Five years on, Lalami turns that same compassion to the silences of the present. In her timely fourth novel, The Other Americans, she follows an investigation into the death of an elderly Moroccan immigrant in an apparent hit-and-run and its impact on a California desert town.