Melanie McFarland in AlterNet:

Look at me, the con artist says. Watch closely so you can see everything I’m doing. We can’t, of course, because we’re not meant to. Yet we fall for frauds because we so want what they promise to be true: easy money, better solutions, painlessness and efficiency. Elizabeth Holmes, the woman at the center of the Theranos scandal and the central subject of “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” dangled all of these offers in front of the world using showy language, a moving personal story and the appearance of expertise and vision. She parlayed her youth, her intellect, her unwavering commitment to success and her connections to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital out of air. By the time she had scammed powerful politicians, wealthy media magnates and an entire drug store chain, she’d amassed enough money to become, for a short time, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. As in truly self-made, not Kylie Jenner self-made. Holmes did not benefit from the cushion of fame or industry wealth. What she had was a story.

Look at me, the con artist says. Watch closely so you can see everything I’m doing. We can’t, of course, because we’re not meant to. Yet we fall for frauds because we so want what they promise to be true: easy money, better solutions, painlessness and efficiency. Elizabeth Holmes, the woman at the center of the Theranos scandal and the central subject of “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” dangled all of these offers in front of the world using showy language, a moving personal story and the appearance of expertise and vision. She parlayed her youth, her intellect, her unwavering commitment to success and her connections to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital out of air. By the time she had scammed powerful politicians, wealthy media magnates and an entire drug store chain, she’d amassed enough money to become, for a short time, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. As in truly self-made, not Kylie Jenner self-made. Holmes did not benefit from the cushion of fame or industry wealth. What she had was a story.

Holmes dropped out of Stanford at 19 and as she charged into the field of biotech, she styled her approach after other great visionaries, such as Steve Jobs and Thomas Edison. She said all the right things and projected the right image. At the height of her company’s fortune, it was valued at $9 billion. If only that estimated worth was based on a product that actually worked. “The Inventor,” debuting Monday at 9 p.m. on HBO, is but the latest examination of massive fraud to draw the public’s attention and fascination. We’re still reeling over the college bribery scandal currently dominating the headlines, which broke only a few months after Hulu’s and Netflix’s separate looks at the Fyre Fest long con became top gossip at the water cooler.

More here.

Every

Every  It is a commonplace that we live in a time of political polarization and culture war, but if culture is considered not in terms of left and right but as a set of attitudes toward the arts, then, at least among people who pay attention to the arts, we live in an era that cherishes consensus. The first consensus is that ours is an age of plenty. There is so much to watch, to hear, to see, to read, that we should count ourselves lucky. We are cursed only by too many options and too little time to consume all the wonderful things on offer. The cultural consumer (Alex or Wendy) is therefore best served by entities that point them to the right products. Find the right products, and you can undergo an experience you can share with your friends, even the thousands of them you’ve never met. Of course, individual people have preferences and interests, so filters, digital or human, will be required. Everyone will have favorites. What’s superfluous is the negative opinion. The negative opinion wastes Alex and Wendy’s time.

It is a commonplace that we live in a time of political polarization and culture war, but if culture is considered not in terms of left and right but as a set of attitudes toward the arts, then, at least among people who pay attention to the arts, we live in an era that cherishes consensus. The first consensus is that ours is an age of plenty. There is so much to watch, to hear, to see, to read, that we should count ourselves lucky. We are cursed only by too many options and too little time to consume all the wonderful things on offer. The cultural consumer (Alex or Wendy) is therefore best served by entities that point them to the right products. Find the right products, and you can undergo an experience you can share with your friends, even the thousands of them you’ve never met. Of course, individual people have preferences and interests, so filters, digital or human, will be required. Everyone will have favorites. What’s superfluous is the negative opinion. The negative opinion wastes Alex and Wendy’s time. Let’s say, for sake of argument, that you don’t believe in God or the supernatural. Is there still a place for talking about transcendence, the sacred, and meaning in life? Some of the above, but not all? Today’s guest, Alan Lightman, brings a unique perspective to these questions, as someone who has worked within both the sciences and the humanities at the highest level. In his most recent book, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine, he makes the case that naturalists should take transcendence seriously. We talk about the assumptions underlying scientific practice, and the implications that the finitude of our lives has for our search for meaning.

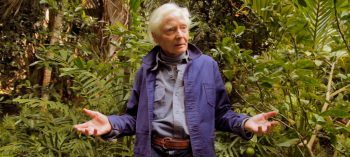

Let’s say, for sake of argument, that you don’t believe in God or the supernatural. Is there still a place for talking about transcendence, the sacred, and meaning in life? Some of the above, but not all? Today’s guest, Alan Lightman, brings a unique perspective to these questions, as someone who has worked within both the sciences and the humanities at the highest level. In his most recent book, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine, he makes the case that naturalists should take transcendence seriously. We talk about the assumptions underlying scientific practice, and the implications that the finitude of our lives has for our search for meaning. Decades ago, economists developed solutions – or variants on the same solution – to the problem of pollution, the key being the imposition of a price on the generation of pollutants such as carbon dioxide (CO2). The idea was to make visible, and accountable, the true environmental costs of any production process.

Decades ago, economists developed solutions – or variants on the same solution – to the problem of pollution, the key being the imposition of a price on the generation of pollutants such as carbon dioxide (CO2). The idea was to make visible, and accountable, the true environmental costs of any production process.

If you tell me to calm down, I probably won’t. The same goes for: “be reasonable,” “get over it already,” “you’re overreacting,” “it was just a joke,” “it’s not such a big deal.” When someone minimizes my feelings, my self-protective reflexes kick in. My body, my mind, my job, my interests, my talents—these are all “mine”—but nothing has quite the power to declare itself as “mine” as a passionate emotion does. When waves of anger or love or grief wash over me, that emotion feels like life itself. It wells up from an innermost core, like my voice, which it usually inflects. And so if you move to tamp it down, I parry by shutting you out: I erect walls around my sanctum sanctorum, to shield the flame of my passion—my life—from your soul-quenching intrusions. Who are you to tell me what I can and cannot feel?!

If you tell me to calm down, I probably won’t. The same goes for: “be reasonable,” “get over it already,” “you’re overreacting,” “it was just a joke,” “it’s not such a big deal.” When someone minimizes my feelings, my self-protective reflexes kick in. My body, my mind, my job, my interests, my talents—these are all “mine”—but nothing has quite the power to declare itself as “mine” as a passionate emotion does. When waves of anger or love or grief wash over me, that emotion feels like life itself. It wells up from an innermost core, like my voice, which it usually inflects. And so if you move to tamp it down, I parry by shutting you out: I erect walls around my sanctum sanctorum, to shield the flame of my passion—my life—from your soul-quenching intrusions. Who are you to tell me what I can and cannot feel?!

Look at me, the con artist says. Watch closely so you can see everything I’m doing. We can’t, of course, because we’re not meant to. Yet we fall for frauds because we so want what they promise to be true: easy money, better solutions, painlessness and efficiency. Elizabeth Holmes, the woman at the center of the Theranos scandal and the central subject of “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” dangled all of these offers in front of the world using showy language, a moving personal story and the appearance of expertise and vision. She parlayed her youth, her intellect, her unwavering commitment to success and her connections to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital out of air. By the time she had scammed powerful politicians, wealthy media magnates and an entire drug store chain, she’d amassed enough money to become, for a short time, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. As in truly self-made, not Kylie Jenner self-made. Holmes did not benefit from the cushion of fame or industry wealth. What she had was a story.

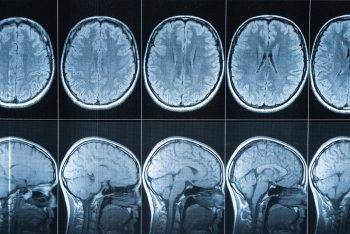

Look at me, the con artist says. Watch closely so you can see everything I’m doing. We can’t, of course, because we’re not meant to. Yet we fall for frauds because we so want what they promise to be true: easy money, better solutions, painlessness and efficiency. Elizabeth Holmes, the woman at the center of the Theranos scandal and the central subject of “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” dangled all of these offers in front of the world using showy language, a moving personal story and the appearance of expertise and vision. She parlayed her youth, her intellect, her unwavering commitment to success and her connections to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital out of air. By the time she had scammed powerful politicians, wealthy media magnates and an entire drug store chain, she’d amassed enough money to become, for a short time, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. As in truly self-made, not Kylie Jenner self-made. Holmes did not benefit from the cushion of fame or industry wealth. What she had was a story. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is typically described by the problems it presents. It is known as a neurological disorder, marked by distractibility, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which begins in childhood and persists in adults. And, indeed, ADHD may have

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is typically described by the problems it presents. It is known as a neurological disorder, marked by distractibility, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which begins in childhood and persists in adults. And, indeed, ADHD may have  The word “immortals” is entwined in my mind with the Jorge Luis Borges’ story titled The Immortals. The story is an exploration of immortal beings imprisoned in the infinite and seeking to understand their condition. This passage in particular speaks a truth about our ideas of immortality.

The word “immortals” is entwined in my mind with the Jorge Luis Borges’ story titled The Immortals. The story is an exploration of immortal beings imprisoned in the infinite and seeking to understand their condition. This passage in particular speaks a truth about our ideas of immortality. As Boeing hustled in 2015 to catch up to Airbus and certify its new 737 MAX, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) managers pushed the agency’s safety engineers to delegate safety assessments to Boeing itself, and to speedily approve the resulting analysis.

As Boeing hustled in 2015 to catch up to Airbus and certify its new 737 MAX, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) managers pushed the agency’s safety engineers to delegate safety assessments to Boeing itself, and to speedily approve the resulting analysis. Last week, Nature, one of the top scientific journals in the world, ran

Last week, Nature, one of the top scientific journals in the world, ran  Until the 1970s, Saudi Arabia was simply a docile U.S. ally and source of cheap oil. That began to change with the OPEC-engineered price hikes, masterminded by the Saudi government. The Saudi government then subsidized the spread of radically fundamentalist Islam through the Muslim world. The stakes increased with the attacks of 9/11 (the majority of the skyjackers were Saudi). But throughout this era, Washington continued to indulge Riyadh, either because of the politics of oil, plain conflicts of interest, the fact that the Saudi policy toward Israel was covertly not as hostile as it might have been, or all three. With the ascension of MBS, a newly bellicose kingdom has emerged. Saudi has reached out to allies in Asia who neglect human rights and are happy to displace U.S. influence. It has engaged in monstrous violations of diplomatic norms, of which the Khashoggi hit was only the most extreme case.

Until the 1970s, Saudi Arabia was simply a docile U.S. ally and source of cheap oil. That began to change with the OPEC-engineered price hikes, masterminded by the Saudi government. The Saudi government then subsidized the spread of radically fundamentalist Islam through the Muslim world. The stakes increased with the attacks of 9/11 (the majority of the skyjackers were Saudi). But throughout this era, Washington continued to indulge Riyadh, either because of the politics of oil, plain conflicts of interest, the fact that the Saudi policy toward Israel was covertly not as hostile as it might have been, or all three. With the ascension of MBS, a newly bellicose kingdom has emerged. Saudi has reached out to allies in Asia who neglect human rights and are happy to displace U.S. influence. It has engaged in monstrous violations of diplomatic norms, of which the Khashoggi hit was only the most extreme case.  The East in you never leaves, I thought, after leaving the immigration bureau. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, here I was in Manhattan, and felt deeply and fully ‘eastern’. What does that mean for somebody who was only ten years old in 1989, whose memories of communism mostly relate to a monument she loved to climb on Gellért Square in Budapest? Simply put, it means a bodily sensation of inexplicable fear at the border. My deep-rooted anxiety about border-guards and law enforcement was back, even in the country where I have chosen to live; where, despite all the problems the United States now faces, I feel deeply at home. In that sense, your ‘eastern’ identity never leaves you, I thought, not even after three decades.

The East in you never leaves, I thought, after leaving the immigration bureau. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, here I was in Manhattan, and felt deeply and fully ‘eastern’. What does that mean for somebody who was only ten years old in 1989, whose memories of communism mostly relate to a monument she loved to climb on Gellért Square in Budapest? Simply put, it means a bodily sensation of inexplicable fear at the border. My deep-rooted anxiety about border-guards and law enforcement was back, even in the country where I have chosen to live; where, despite all the problems the United States now faces, I feel deeply at home. In that sense, your ‘eastern’ identity never leaves you, I thought, not even after three decades. The sun was setting in Hawaii on a spring day in 1995, when W. S. Merwin invited me into his study to hear him recite a new poem, and since he did not care to turn on the lights I listened to the last stanzas of his “Lament for the Makers” in near darkness. His study had a sacred aspect—its door was to remain locked whenever I house-sat for him and his wife, Paula, during their travels to the mainland and then to their place in the Dordogne. This atmosphere was heightened by his melodic voice, which in my mind bore traces of the hymns he had composed as a child for his Presbyterian minister father in Scranton, Pennsylvania. A palm frond crashed into the ravine beyond the lanai, on which a pair of sleeping chow chows did not stir. William recalled his departed poet-friends: “One by one they have all gone / out of the time and language we / had in common which have brought me”—and here his voice began to crack: “to this season after them.”

The sun was setting in Hawaii on a spring day in 1995, when W. S. Merwin invited me into his study to hear him recite a new poem, and since he did not care to turn on the lights I listened to the last stanzas of his “Lament for the Makers” in near darkness. His study had a sacred aspect—its door was to remain locked whenever I house-sat for him and his wife, Paula, during their travels to the mainland and then to their place in the Dordogne. This atmosphere was heightened by his melodic voice, which in my mind bore traces of the hymns he had composed as a child for his Presbyterian minister father in Scranton, Pennsylvania. A palm frond crashed into the ravine beyond the lanai, on which a pair of sleeping chow chows did not stir. William recalled his departed poet-friends: “One by one they have all gone / out of the time and language we / had in common which have brought me”—and here his voice began to crack: “to this season after them.” The data gap is particularly dangerous, and maddening, in medical research. Women are severely under-represented in clinical trials, which means we could be missing out on drugs that work for us and are regularly prescribed inappropriate drugs, or inappropriate doses. As a result, women are significantly more likely than men to suffer adverse drug reactions. Scientists don’t even know the specific effects on women of a huge number of existing medications. This is alarming. We now know, for instance, that one commonly prescribed drug for high blood pressure lowers heart-attack deaths among men but increases them for women. One of my mother’s closest friends died of a heart attack within a few hours of visiting her GP, complaining of excruciating abdominal pain. Women are more likely than men to suffer fatal heart

The data gap is particularly dangerous, and maddening, in medical research. Women are severely under-represented in clinical trials, which means we could be missing out on drugs that work for us and are regularly prescribed inappropriate drugs, or inappropriate doses. As a result, women are significantly more likely than men to suffer adverse drug reactions. Scientists don’t even know the specific effects on women of a huge number of existing medications. This is alarming. We now know, for instance, that one commonly prescribed drug for high blood pressure lowers heart-attack deaths among men but increases them for women. One of my mother’s closest friends died of a heart attack within a few hours of visiting her GP, complaining of excruciating abdominal pain. Women are more likely than men to suffer fatal heart