Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

In 1995, if you had told Toby Spribille that he’d eventually overthrow a scientific idea that’s been the stuff of textbooks for 150 years, he would have laughed at you. Back then, his life seemed constrained to a very different path. He was raised in a Montana trailer park, and home-schooled by what he now describes as a “fundamentalist cult.” At a young age, he fell in love with science, but had no way of feeding that love. He longed to break away from his roots and get a proper education.

In 1995, if you had told Toby Spribille that he’d eventually overthrow a scientific idea that’s been the stuff of textbooks for 150 years, he would have laughed at you. Back then, his life seemed constrained to a very different path. He was raised in a Montana trailer park, and home-schooled by what he now describes as a “fundamentalist cult.” At a young age, he fell in love with science, but had no way of feeding that love. He longed to break away from his roots and get a proper education.

At 19, he got a job at a local forestry service. Within a few years, he had earned enough to leave home. His meager savings and non-existent grades meant that no American university would take him, so Spribille looked to Europe.

Thanks to his family background, he could speak German, and he had heard that many universities there charged no tuition fees. His missing qualifications were still a problem, but one that the University of Gottingen decided to overlook. “They said that under exceptional circumstances, they could enroll a few people every year without transcripts,” says Spribille. “That was the bottleneck of my life.”

Throughout his undergraduate and postgraduate work, Spribille became an expert on the organisms that had grabbed his attention during his time in the Montana forests—lichens.

More here.

Identity politics is one of the defining – and one of the most divisive – issues of our age. And no identity is more contested or fought over than white identity. For some it is a means of giving voice to a group whose identity has previously been denied. For others it is simply as an expression of racism.

Identity politics is one of the defining – and one of the most divisive – issues of our age. And no identity is more contested or fought over than white identity. For some it is a means of giving voice to a group whose identity has previously been denied. For others it is simply as an expression of racism. WHAT A STRANGE

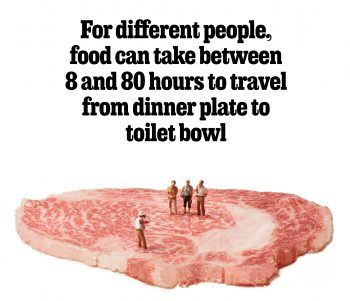

WHAT A STRANGE As a general rule it is true that if you eat vastly fewer calories than you burn, you’ll get slimmer (and if you consume far more, you’ll get fatter). But the myriad faddy diets flogged to us each year belie the simplicity of the formula that Camacho was given. The calorie as a scientific measurement is not in dispute. But calculating the exact calorific content of food is far harder than the confidently precise numbers displayed on food packets suggest. Two items of food with identical calorific values may be digested in very different ways. Each body processes calories differently. Even for a single individual, the time of day that you eat matters. The more we probe, the more we realise that tallying calories will do little to help us control our weight or even maintain a healthy diet: the beguiling simplicity of counting calories in and calories out is dangerously flawed. The calorie is ubiquitous in daily life. It takes top billing on the information label of most packaged food and drinks. Ever more restaurants list the number of calories in each dish on their menus. Counting the calories we expend has become just as standard. Gym equipment, fitness devices around our wrists, even our phones tell us how many calories we have supposedly burned in a single exercise session or over the course of a day.

As a general rule it is true that if you eat vastly fewer calories than you burn, you’ll get slimmer (and if you consume far more, you’ll get fatter). But the myriad faddy diets flogged to us each year belie the simplicity of the formula that Camacho was given. The calorie as a scientific measurement is not in dispute. But calculating the exact calorific content of food is far harder than the confidently precise numbers displayed on food packets suggest. Two items of food with identical calorific values may be digested in very different ways. Each body processes calories differently. Even for a single individual, the time of day that you eat matters. The more we probe, the more we realise that tallying calories will do little to help us control our weight or even maintain a healthy diet: the beguiling simplicity of counting calories in and calories out is dangerously flawed. The calorie is ubiquitous in daily life. It takes top billing on the information label of most packaged food and drinks. Ever more restaurants list the number of calories in each dish on their menus. Counting the calories we expend has become just as standard. Gym equipment, fitness devices around our wrists, even our phones tell us how many calories we have supposedly burned in a single exercise session or over the course of a day. Last April, in the famous Faraday Theatre at the Royal Institution in London, Carlo Rovelli gave an hour-long lecture on the nature of time. A red thread spanned the stage, a metaphor for the Italian theoretical physicist’s subject. “Time is a long line,” he said. To the left lies the past—the dinosaurs, the big bang—and to the right, the future—the unknown. “We’re sort of here,” he said, hanging a carabiner on it, as a marker for the present. Then he flipped the script. “I’m going to tell you that time is not like that,” he explained.

Last April, in the famous Faraday Theatre at the Royal Institution in London, Carlo Rovelli gave an hour-long lecture on the nature of time. A red thread spanned the stage, a metaphor for the Italian theoretical physicist’s subject. “Time is a long line,” he said. To the left lies the past—the dinosaurs, the big bang—and to the right, the future—the unknown. “We’re sort of here,” he said, hanging a carabiner on it, as a marker for the present. Then he flipped the script. “I’m going to tell you that time is not like that,” he explained. The pub is warm and beery. Grog glasses—drained, foam stained—scatter sticky veneer. Red-wine lips, hoppy breath, a slurry of slurring; laughter like gunfire, craic-ing off the wood panels, mirror walls and ranks of whiskey bottles. Bar talk is of theology and adultery, literature and death, soap and sausages. Everything and nothing, discussed or daydreamed over a quick cheese sandwich. A nothing old day. But the stuff of life—infinitesimal yet essential—all the same . . .

The pub is warm and beery. Grog glasses—drained, foam stained—scatter sticky veneer. Red-wine lips, hoppy breath, a slurry of slurring; laughter like gunfire, craic-ing off the wood panels, mirror walls and ranks of whiskey bottles. Bar talk is of theology and adultery, literature and death, soap and sausages. Everything and nothing, discussed or daydreamed over a quick cheese sandwich. A nothing old day. But the stuff of life—infinitesimal yet essential—all the same . . . One of the key misconceptions about solar geoengineering — putting aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight and reduce global warming — is that it could be used as a fix-all to reverse global warming trends and bring temperature back to pre-industrial levels.

One of the key misconceptions about solar geoengineering — putting aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight and reduce global warming — is that it could be used as a fix-all to reverse global warming trends and bring temperature back to pre-industrial levels. The United States and India, two of the world’s largest and oldest democracies, are both governed on the basis of written constitutions. One of the inspirations for the Constitution of India, drafted between 1947 and 1950, was the US Constitution. Both Indians and Americans revere their ‘constitutional rights’ – especially the ‘fundamental right’ of free speech, and the separation of state and religion. Both countries support critical traditions that focus on particular clauses of the constitution. In India, Article 356, which allows for the suspension of state legislative assemblies to permit ‘direct rule by the centre’, has provoked considerable critique, while in the US, the Second Amendment is a source of perpetual political and legal discord. The Indian and US supreme courts both enjoy the power of judicial review, to declare acts of other branches of government illegitimate, and so a measure of ‘supremacy’ over their respective legislative branches. For this reason, both constitutions are ‘undemocratic’ in their arrogation of too much political power to the judicial bench – a group of unelected public servants.

The United States and India, two of the world’s largest and oldest democracies, are both governed on the basis of written constitutions. One of the inspirations for the Constitution of India, drafted between 1947 and 1950, was the US Constitution. Both Indians and Americans revere their ‘constitutional rights’ – especially the ‘fundamental right’ of free speech, and the separation of state and religion. Both countries support critical traditions that focus on particular clauses of the constitution. In India, Article 356, which allows for the suspension of state legislative assemblies to permit ‘direct rule by the centre’, has provoked considerable critique, while in the US, the Second Amendment is a source of perpetual political and legal discord. The Indian and US supreme courts both enjoy the power of judicial review, to declare acts of other branches of government illegitimate, and so a measure of ‘supremacy’ over their respective legislative branches. For this reason, both constitutions are ‘undemocratic’ in their arrogation of too much political power to the judicial bench – a group of unelected public servants. T

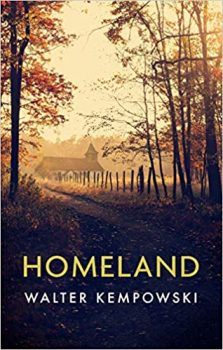

T Homeland is essentially a road trip novel, but its road trip doesn’t work. Contra to the willful American model of making off into the great vistas of the West, Jonathan and his feckless companions (a racing driver and a sexist caricature of a press officer, Frau Winkelvoss) can’t escape the traumas of East Prussia’s landscape. To paraphrase Joan Didion, history has very much bloodied the land here, leaving it irrevocably besmirched and hard to navigate (as the aptly titled Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder can attest). Instead of experiencing the desired transcendental realization while standing on the Vistula Spit, Jonathan thinks about the “chests of drawers and grandfather clocks” on wagons making their way across the Wisła while under fire from British bombers and Red Army tanks, and that when the ferries crammed with refugees sank, and the dishes in their mahogany dining rooms slid to the floor, “no-one sang hymns.” The final pages of the novel see him scooping some sand from the presumed spot of his father’s death into a medicine bottle, with the vague hope that a forensic lab will be able to analyze it for DNA — a final bathetic pun on the notion of the German fatherland.

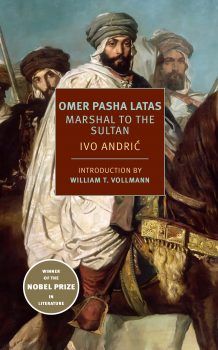

Homeland is essentially a road trip novel, but its road trip doesn’t work. Contra to the willful American model of making off into the great vistas of the West, Jonathan and his feckless companions (a racing driver and a sexist caricature of a press officer, Frau Winkelvoss) can’t escape the traumas of East Prussia’s landscape. To paraphrase Joan Didion, history has very much bloodied the land here, leaving it irrevocably besmirched and hard to navigate (as the aptly titled Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder can attest). Instead of experiencing the desired transcendental realization while standing on the Vistula Spit, Jonathan thinks about the “chests of drawers and grandfather clocks” on wagons making their way across the Wisła while under fire from British bombers and Red Army tanks, and that when the ferries crammed with refugees sank, and the dishes in their mahogany dining rooms slid to the floor, “no-one sang hymns.” The final pages of the novel see him scooping some sand from the presumed spot of his father’s death into a medicine bottle, with the vague hope that a forensic lab will be able to analyze it for DNA — a final bathetic pun on the notion of the German fatherland. Andrić is particularly remarkable for his psychological acuity. Consider the knot of complexity that is Omer Pasha: born Mićo Latas, he’d been a brilliant boy in a village too small to contain his ambitions. He was bored by his parents and the provincial people around him. He managed to acquire a scholarship to military school—Austrian, not Turkish—but, just as he is ready to graduate, he receives word that his father, a minor officer, “a weak man…a small, overlooked man,” has been indicted for misuse of state funds. The stigma will prevent Mićo from achieving any career at all. This is when he takes off for Istanbul to scrape together an entirely new life.

Andrić is particularly remarkable for his psychological acuity. Consider the knot of complexity that is Omer Pasha: born Mićo Latas, he’d been a brilliant boy in a village too small to contain his ambitions. He was bored by his parents and the provincial people around him. He managed to acquire a scholarship to military school—Austrian, not Turkish—but, just as he is ready to graduate, he receives word that his father, a minor officer, “a weak man…a small, overlooked man,” has been indicted for misuse of state funds. The stigma will prevent Mićo from achieving any career at all. This is when he takes off for Istanbul to scrape together an entirely new life. The New Zealand killer takes his place in the cracked pantheon of violent, Trump-admiring extremists: beside the gunman at the Tree of Life synagogue, in Pittsburgh, who blamed Jews for resettling refugees and immigrants, whom Trump vilifies as the center of his politics; beside the van-dweller in Miami who found purpose amid the throngs of Trump rallies and set about sending pipe bombs to George Soros, journalists, and Democrats. The New Zealand killer did not exact his violence in America, but

The New Zealand killer takes his place in the cracked pantheon of violent, Trump-admiring extremists: beside the gunman at the Tree of Life synagogue, in Pittsburgh, who blamed Jews for resettling refugees and immigrants, whom Trump vilifies as the center of his politics; beside the van-dweller in Miami who found purpose amid the throngs of Trump rallies and set about sending pipe bombs to George Soros, journalists, and Democrats. The New Zealand killer did not exact his violence in America, but  Maybe because we’re living in a dystopia, it feels as if we’ve become obsessed with prophecy of late. Protest signs at the 2017 Women’s March read “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!” and “Octavia Warned Us.” News headlines about abortion bans and the defunding of Planned Parenthood do seem ripped from the pages of Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985). And Octavia Butler’s “Parable” series, published in the 1990s, did eerily feature a presidential candidate who vows to “make America great again.”

Maybe because we’re living in a dystopia, it feels as if we’ve become obsessed with prophecy of late. Protest signs at the 2017 Women’s March read “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!” and “Octavia Warned Us.” News headlines about abortion bans and the defunding of Planned Parenthood do seem ripped from the pages of Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985). And Octavia Butler’s “Parable” series, published in the 1990s, did eerily feature a presidential candidate who vows to “make America great again.” To be sure, the bipartisan civic ethos is an indispensable ingredient of a flourishing democracy. But it cannot be cultivated under conditions where everything we do is plausibly regarded an expression of our political loyalties. When politics is all we ever do together, our efforts to repair democracy by means of strategies for enacting better politics are doomed simply to backfire. What is required instead is the reclaiming of regions of social space for shared activities that are in no way political, occasions for cooperative endeavors in which the participants’ political affiliations are not merely suppressed or bracketed, but irrelevant and out of place. If you now find yourself wondering whether such collaborations could possibly exist, you have placed your finger firmly on the problem of polarization. For polarization has led not only to the colonization of our social environments by politics, it also has enabled politics to seize and confine our social imagination. That we must struggle to conceptualize avenues of social collaboration that are not structured around our political identities is the fullest manifestation of the problem of polarization. To frame the upshot somewhat paradoxically, if we want to repair our democracy, we need to focus our collective attention elsewhere.

To be sure, the bipartisan civic ethos is an indispensable ingredient of a flourishing democracy. But it cannot be cultivated under conditions where everything we do is plausibly regarded an expression of our political loyalties. When politics is all we ever do together, our efforts to repair democracy by means of strategies for enacting better politics are doomed simply to backfire. What is required instead is the reclaiming of regions of social space for shared activities that are in no way political, occasions for cooperative endeavors in which the participants’ political affiliations are not merely suppressed or bracketed, but irrelevant and out of place. If you now find yourself wondering whether such collaborations could possibly exist, you have placed your finger firmly on the problem of polarization. For polarization has led not only to the colonization of our social environments by politics, it also has enabled politics to seize and confine our social imagination. That we must struggle to conceptualize avenues of social collaboration that are not structured around our political identities is the fullest manifestation of the problem of polarization. To frame the upshot somewhat paradoxically, if we want to repair our democracy, we need to focus our collective attention elsewhere.