James McBride in The New York Times:

Toni Morrison, the author and Nobel Prize winner, turned 88 on Feb. 18. I have never met Morrison. And while you’ll likely see a donkey fly before you see her stand before a bunch of Harvard undergraduates and sing on demand, the fact is Toni Morrison is very much like Ella Fitzgerald. Like Fitzgerald, she rose from humble beginnings to world prominence. Like Fitzgerald, she is intensely private. And like Fitzgerald, she has given every iota of her extraordinary American-born talent and intellect to the great American dream. Not the one with the guns and bombs bursting in air. The other one, the one with world peace, justice, racial harmony, art, literature, music and language that shows us how to be free wrapped in it. Morrison has, as they say in church, lived a life of service. Whatever awards and acclaim she has won, she has earned. She has paid in full. She owes us nothing.

Toni Morrison, the author and Nobel Prize winner, turned 88 on Feb. 18. I have never met Morrison. And while you’ll likely see a donkey fly before you see her stand before a bunch of Harvard undergraduates and sing on demand, the fact is Toni Morrison is very much like Ella Fitzgerald. Like Fitzgerald, she rose from humble beginnings to world prominence. Like Fitzgerald, she is intensely private. And like Fitzgerald, she has given every iota of her extraordinary American-born talent and intellect to the great American dream. Not the one with the guns and bombs bursting in air. The other one, the one with world peace, justice, racial harmony, art, literature, music and language that shows us how to be free wrapped in it. Morrison has, as they say in church, lived a life of service. Whatever awards and acclaim she has won, she has earned. She has paid in full. She owes us nothing.

Yet even as she moves into the October of life, Morrison, quietly and without ceremony, lays another gem at our feet. “The Source of Self-Regard” is a book of essays, lectures and meditations, a reminder that the old music is still the best, that in this time of tumult and sadness and continuous war, where tawdry words are blasted about like junk food, and the nation staggers from one crisis to the next, led by a president with all the grace of a Cyclops and a brain the size of a full-grown pea, the mightiness, the stillness, the pure power and beauty of words delivered in thought, reason and discourse, still carry the unstoppable force of a thousand hammer blows, spreading the salve of righteousness that can heal our nation and restore the future our children deserve. This book demonstrates once again that Morrison is more than the standard-bearer of American literature.

She is our greatest singer. And this book is perhaps her most important song.

More here.

Were the humanists wrong to claim that art is good for us, “like Ovaltine and yoga”? Movies have been more like a secret vice, the first and most invasive of the technologies that have progressively estranged us from one another. As a Londoner resettled in San Francisco, Thomson is also keenly aware of the way the medium has duped Americans, convincing them that happy endings are inevitable so long as gun-toting men control the narrative. “Can’t we admit,” he asks, “how much American experience has been rooted in fear?” In one mind-bending paragraph he outlines an alternative pantheon of great American films – including

Were the humanists wrong to claim that art is good for us, “like Ovaltine and yoga”? Movies have been more like a secret vice, the first and most invasive of the technologies that have progressively estranged us from one another. As a Londoner resettled in San Francisco, Thomson is also keenly aware of the way the medium has duped Americans, convincing them that happy endings are inevitable so long as gun-toting men control the narrative. “Can’t we admit,” he asks, “how much American experience has been rooted in fear?” In one mind-bending paragraph he outlines an alternative pantheon of great American films – including  “Bloodlines” employs numbered sections, one of Carreira’s favored devices, to divide the poem into a triptych. She uses time and place to distinguish each, taking us from her adolescence in Portugal to early adulthood in New Jersey to the present moment. In the first, the adolescent version of Carreira feels shame about her body—not the first time we encounter, in heartbreaking fashion, the painful self-consciousness of a young narrator—while, at the same time yearning for physical connection. She wants “a God-fearing man,” but she observes that a young neighbor of hers is “a pretty boy.” The end of this section is marked by the advent of menstruation, a hallmark of maturity that doubles as a sign of heritage and hardship. While the neighbor boy collects the material possessions that “make for a good life,” the menstrual signature on the speaker’s bed sheets “promises thorns no bread or gold can dull.” The concrete trappings of health and prosperity are conflated with the promise of a bright future, but “blood,” in all its multi-layered meaning, complicates the simple promise of “bread or gold.” Profoundly, for Carreira, this duality echoes the divided heart of the Portuguese immigrant community in America—one heart striving and struggling forward in its quest for material security and the American Dream, while the other looks backward toward an idealized past that continues to drift further and further out of reach with the passage of time.

“Bloodlines” employs numbered sections, one of Carreira’s favored devices, to divide the poem into a triptych. She uses time and place to distinguish each, taking us from her adolescence in Portugal to early adulthood in New Jersey to the present moment. In the first, the adolescent version of Carreira feels shame about her body—not the first time we encounter, in heartbreaking fashion, the painful self-consciousness of a young narrator—while, at the same time yearning for physical connection. She wants “a God-fearing man,” but she observes that a young neighbor of hers is “a pretty boy.” The end of this section is marked by the advent of menstruation, a hallmark of maturity that doubles as a sign of heritage and hardship. While the neighbor boy collects the material possessions that “make for a good life,” the menstrual signature on the speaker’s bed sheets “promises thorns no bread or gold can dull.” The concrete trappings of health and prosperity are conflated with the promise of a bright future, but “blood,” in all its multi-layered meaning, complicates the simple promise of “bread or gold.” Profoundly, for Carreira, this duality echoes the divided heart of the Portuguese immigrant community in America—one heart striving and struggling forward in its quest for material security and the American Dream, while the other looks backward toward an idealized past that continues to drift further and further out of reach with the passage of time. Diderot is known to the casual reader chiefly as an editor of the Encyclopédie—it had no other name, for there was no other encyclopédie. Since the Encyclopédie was a massive compendium of knowledge of all kinds, organizing the entirety of human thought, Diderot persists vaguely in memory as a type of Enlightenment superman, the big bore with a big book. Yet in these two new works of biography he turns out to be not a severe rationalist, overseeing a totalitarianism of thought, but an inspired and lovable amateur, with an opinion on every subject and an appetite for every occasion.

Diderot is known to the casual reader chiefly as an editor of the Encyclopédie—it had no other name, for there was no other encyclopédie. Since the Encyclopédie was a massive compendium of knowledge of all kinds, organizing the entirety of human thought, Diderot persists vaguely in memory as a type of Enlightenment superman, the big bore with a big book. Yet in these two new works of biography he turns out to be not a severe rationalist, overseeing a totalitarianism of thought, but an inspired and lovable amateur, with an opinion on every subject and an appetite for every occasion. In 2015 I attended a workshop on political polarization with an eclectic group of scholars and activists. We swapped ideas on resolving battles over climate change, inequality, abortion and gay rights. One obstacle to compromise, a psychologist said, is that many Americans have a visceral, emotional reaction to issues like homosexuality.

In 2015 I attended a workshop on political polarization with an eclectic group of scholars and activists. We swapped ideas on resolving battles over climate change, inequality, abortion and gay rights. One obstacle to compromise, a psychologist said, is that many Americans have a visceral, emotional reaction to issues like homosexuality. In my 50s, too old to become a real expert, I have finally fallen in love with algebraic geometry. As the name suggests, this is the study of geometry using algebra. Around 1637, René Descartes laid the groundwork for this subject by taking a plane, mentally drawing a grid on it, as we now do with graph paper, and calling the coordinates x and y. We can write down an equation like x2+ y2 = 1, and there will be a curve consisting of points whose coordinates obey this equation. In this example, we get a circle!

In my 50s, too old to become a real expert, I have finally fallen in love with algebraic geometry. As the name suggests, this is the study of geometry using algebra. Around 1637, René Descartes laid the groundwork for this subject by taking a plane, mentally drawing a grid on it, as we now do with graph paper, and calling the coordinates x and y. We can write down an equation like x2+ y2 = 1, and there will be a curve consisting of points whose coordinates obey this equation. In this example, we get a circle! With his reckless “pre-emptive” airstrike on

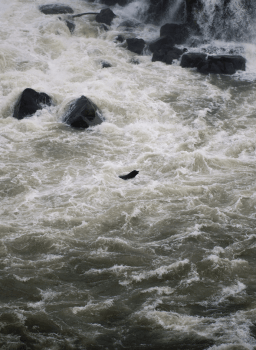

With his reckless “pre-emptive” airstrike on  In 1974, after protracted legal efforts and sometimes violent protests, a US district court in Washington State upheld the treaties of the Columbia Plateau tribes. Known as the Boldt Decision, the ruling upended the fishing industry and still angers non-Indian fishermen. It gave tribal members the right to half of the river’s harvestable fish, and it was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1979. (The number considered harvestable varies. Fishery managers meet throughout the year to set limits that will allow weak populations to rebound and tributary stocks to spawn, but the shares are always kept equal between treaty and non-treaty fishers.) The tribes also have access to thirty-one fishing sites closed to others. A long stretch of the lower river is now divided into six fishing zones. The first five zones are in the 145 miles between the mouth of the Columbia and Bonneville Dam. Zone 6 runs above Bonneville for another 147 miles, and commercial fishing can only be done by the tribes there. The Boldt Decision affirmed the right to fish—but it didn’t bring back the fish. It did nothing to mitigate the desperate losses caused by dams, development, and overfishing. By 1995, there were about 750,000 salmon left in the entire Columbia River.

In 1974, after protracted legal efforts and sometimes violent protests, a US district court in Washington State upheld the treaties of the Columbia Plateau tribes. Known as the Boldt Decision, the ruling upended the fishing industry and still angers non-Indian fishermen. It gave tribal members the right to half of the river’s harvestable fish, and it was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1979. (The number considered harvestable varies. Fishery managers meet throughout the year to set limits that will allow weak populations to rebound and tributary stocks to spawn, but the shares are always kept equal between treaty and non-treaty fishers.) The tribes also have access to thirty-one fishing sites closed to others. A long stretch of the lower river is now divided into six fishing zones. The first five zones are in the 145 miles between the mouth of the Columbia and Bonneville Dam. Zone 6 runs above Bonneville for another 147 miles, and commercial fishing can only be done by the tribes there. The Boldt Decision affirmed the right to fish—but it didn’t bring back the fish. It did nothing to mitigate the desperate losses caused by dams, development, and overfishing. By 1995, there were about 750,000 salmon left in the entire Columbia River. Cheesemania ’93, as I’ve decided to call it, is a classic TV commercial. In a civilization organized primarily around the funneling of capital to corporations, commercials offer a space of transcendent communion with the objects of our dependence and desire. They take place in a realm understood to be ideational without quite being imaginary—existing not in any one person’s mind, but ambiently, on a level of reality we rarely think to question, encoded in the daily order of things as neatly as the peanut butter aisle of a suburban grocery store. (This bare proximity to capitalism’s exposed nerves, combined with a habitual callousness to human dignity, is I believe why, in the

Cheesemania ’93, as I’ve decided to call it, is a classic TV commercial. In a civilization organized primarily around the funneling of capital to corporations, commercials offer a space of transcendent communion with the objects of our dependence and desire. They take place in a realm understood to be ideational without quite being imaginary—existing not in any one person’s mind, but ambiently, on a level of reality we rarely think to question, encoded in the daily order of things as neatly as the peanut butter aisle of a suburban grocery store. (This bare proximity to capitalism’s exposed nerves, combined with a habitual callousness to human dignity, is I believe why, in the  Fiona MacCarthy met Walter Gropius (1883–1969) through Jack Pritchard, the British entrepreneur who built Lawn Road Flats in Hampstead, an experiment in modernist living where Gropius took up residence after escaping Nazi Germany in 1934. The Bauhaus, the school he founded in Weimar a century ago this year, had been closed by stormtroopers the previous year (by then it had moved to Berlin). In 1968, after the opening of a Bauhaus exhibition at the Royal Academy, MacCarthy was invited to dinner with Gropius at the Lawn Road Isobar, the block’s in-house dining room: ‘He was then eighty-five, small, upright, very courteous, retaining a Germanic formality of bearing,’ MacCarthy recalled. He ‘was still valiant and impressive, with a flickering of arrogance’.

Fiona MacCarthy met Walter Gropius (1883–1969) through Jack Pritchard, the British entrepreneur who built Lawn Road Flats in Hampstead, an experiment in modernist living where Gropius took up residence after escaping Nazi Germany in 1934. The Bauhaus, the school he founded in Weimar a century ago this year, had been closed by stormtroopers the previous year (by then it had moved to Berlin). In 1968, after the opening of a Bauhaus exhibition at the Royal Academy, MacCarthy was invited to dinner with Gropius at the Lawn Road Isobar, the block’s in-house dining room: ‘He was then eighty-five, small, upright, very courteous, retaining a Germanic formality of bearing,’ MacCarthy recalled. He ‘was still valiant and impressive, with a flickering of arrogance’.

Variations of the genome editor CRISPR have wowed biology labs around the world over the past few years because they can precisely change single DNA bases, promising deft repairs for genetic diseases and improvements in crop and livestock genomes. But such “base editors” can have a serious weakness. A pair of studies published online in Science this week

Variations of the genome editor CRISPR have wowed biology labs around the world over the past few years because they can precisely change single DNA bases, promising deft repairs for genetic diseases and improvements in crop and livestock genomes. But such “base editors” can have a serious weakness. A pair of studies published online in Science this week