Ryan Holmberg at the NYRB:

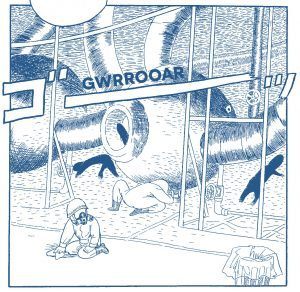

In October 2011, seven months after the tsunami and meltdowns, a second collection of the artist’s work was published in Japan, again to much acclaim. Titled Deep Sea Fish (Shinkaigyō), the volume reprinted stories that Katsumata drew in the 1980s about the disposable laborers who clean and maintain Japan’s nuclear power plants, as well as others he wrote in the 1970s dealing (sometimes indirectly) with the way industrialization had upended the Japanese countryside, creating a new class of alienated immigrants in the cities and a world of vanishing fables in the interior. This juxtaposition reflects the trajectory of the artist’s own life. He was born and raised in a farming village named Kahoku-cho, located on the Kitakami River just north of the major port city of Ishinomaki in northern Japan. Here, he spent his non-school hours reading comics and tending the family cows. After graduating high school in 1962, Katsumata moved to Tokyo to take up a job selling high-end laboratory equipment for a subsidiary of Hitachi. In 1965, he entered Tokyo University of Education, got a degree in physics, and began a master’s in nuclear physics, but quit in 1971 to focus full-time on cartooning.

In October 2011, seven months after the tsunami and meltdowns, a second collection of the artist’s work was published in Japan, again to much acclaim. Titled Deep Sea Fish (Shinkaigyō), the volume reprinted stories that Katsumata drew in the 1980s about the disposable laborers who clean and maintain Japan’s nuclear power plants, as well as others he wrote in the 1970s dealing (sometimes indirectly) with the way industrialization had upended the Japanese countryside, creating a new class of alienated immigrants in the cities and a world of vanishing fables in the interior. This juxtaposition reflects the trajectory of the artist’s own life. He was born and raised in a farming village named Kahoku-cho, located on the Kitakami River just north of the major port city of Ishinomaki in northern Japan. Here, he spent his non-school hours reading comics and tending the family cows. After graduating high school in 1962, Katsumata moved to Tokyo to take up a job selling high-end laboratory equipment for a subsidiary of Hitachi. In 1965, he entered Tokyo University of Education, got a degree in physics, and began a master’s in nuclear physics, but quit in 1971 to focus full-time on cartooning.

more here.

IT’S BEEN TEN YEARS NOW

IT’S BEEN TEN YEARS NOW  Graves’s life was, in every sense, chaotic, but purposely so. He believed that ‘tranquillity’ (the Wordsworthian recipe) narcotises true poetry. The poet, like the kettle, must boil to produce. A few weeks before Graves started on Good-bye to All That, Riding enlarged the ménageto quatre with an Irish literary adventurer. It went all wrong and she jumped out of a fourth-floor window in Hammersmith. Graves followed suit. Both survived.

Graves’s life was, in every sense, chaotic, but purposely so. He believed that ‘tranquillity’ (the Wordsworthian recipe) narcotises true poetry. The poet, like the kettle, must boil to produce. A few weeks before Graves started on Good-bye to All That, Riding enlarged the ménageto quatre with an Irish literary adventurer. It went all wrong and she jumped out of a fourth-floor window in Hammersmith. Graves followed suit. Both survived. This story begins nearly four billion years ago, when the Earth was just another rock in just another solar system. In a pool of sludge on that rock, something astonishing happened. A long stringy molecule found a way to copy itself. Similar molecules would later carry the code that would enable life forms to grow, digest, run, breathe, read, launch rockets to the Moon. But for now, that molecule only knew how to do a single, important thing – to reproduce. This was the moment that life emerged. Since then, as each living organism has multiplied, the codes of life have altered by the tiniest increments generation after generation, stretching across time. Most of these mutations have had little impact. Very, very occasionally, they have been extraordinarily useful. The sum of millions of minuscule modifications over billions of generations has given some organisms the ability to survive in water, land, ice or the desert. They have helped them to beat disease, to be stronger, faster, fly. Across the aeons of biological time, this process has led one particular organism – us – to grow large brains, develop opposable thumbs and communicate complex ideas. We’ve mastered fire, tools, technology. In the great span of evolution, this transformation happened a mere split second ago. Degree by degree we continue to change.

This story begins nearly four billion years ago, when the Earth was just another rock in just another solar system. In a pool of sludge on that rock, something astonishing happened. A long stringy molecule found a way to copy itself. Similar molecules would later carry the code that would enable life forms to grow, digest, run, breathe, read, launch rockets to the Moon. But for now, that molecule only knew how to do a single, important thing – to reproduce. This was the moment that life emerged. Since then, as each living organism has multiplied, the codes of life have altered by the tiniest increments generation after generation, stretching across time. Most of these mutations have had little impact. Very, very occasionally, they have been extraordinarily useful. The sum of millions of minuscule modifications over billions of generations has given some organisms the ability to survive in water, land, ice or the desert. They have helped them to beat disease, to be stronger, faster, fly. Across the aeons of biological time, this process has led one particular organism – us – to grow large brains, develop opposable thumbs and communicate complex ideas. We’ve mastered fire, tools, technology. In the great span of evolution, this transformation happened a mere split second ago. Degree by degree we continue to change. Elephants ought to get a lot of cancer. They’re huge animals, weighing as much as eight tons. It takes a lot of cells to make up that much elephant. All of those cells arose from a single fertilized egg, and each time a cell divides, there’s a chance that it will gain a mutation — one that may lead to cancer. Strangely, however, elephants aren’t more prone to cancer than smaller animals. Some research even suggests they

Elephants ought to get a lot of cancer. They’re huge animals, weighing as much as eight tons. It takes a lot of cells to make up that much elephant. All of those cells arose from a single fertilized egg, and each time a cell divides, there’s a chance that it will gain a mutation — one that may lead to cancer. Strangely, however, elephants aren’t more prone to cancer than smaller animals. Some research even suggests they  We (the readers of 3QD; I know there are many people who disagree) can take it as given that Alex Jones is a thoroughly evil person. Someone who spreads false statements that the parents of the children killed in the Sandy Hook shooting staged the whole thing deserves lots of bad things happening to him, e.g. lose all the money he has made from the web in a defamation suit that the parents have filed, have people boycott his dietary supplement hoax.

We (the readers of 3QD; I know there are many people who disagree) can take it as given that Alex Jones is a thoroughly evil person. Someone who spreads false statements that the parents of the children killed in the Sandy Hook shooting staged the whole thing deserves lots of bad things happening to him, e.g. lose all the money he has made from the web in a defamation suit that the parents have filed, have people boycott his dietary supplement hoax.

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Polynesia could swallow up the entire north Atlantic Ocean. It’s that big.

Polynesia could swallow up the entire north Atlantic Ocean. It’s that big.  spanning George Boole to Claude Shannon. By some measures the works of these men combine to give us our modern, programmable computer.

spanning George Boole to Claude Shannon. By some measures the works of these men combine to give us our modern, programmable computer.

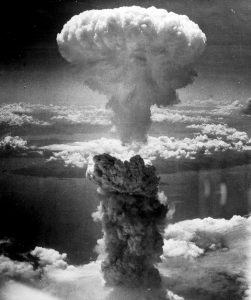

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops?

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops?

The movement for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel – known as BDS – has been driving the world a little bit mad. Since its founding 13 years ago, it has acquired nearly as many enemies as the Israelis and Palestinians combined. It has hindered the efforts of Arab states to fully break their own decades-old boycott in pursuit of increasingly overt cooperation with

The movement for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel – known as BDS – has been driving the world a little bit mad. Since its founding 13 years ago, it has acquired nearly as many enemies as the Israelis and Palestinians combined. It has hindered the efforts of Arab states to fully break their own decades-old boycott in pursuit of increasingly overt cooperation with  It’s one of the greatest stories in science, right up there with Neil Armstrong’s small step on the moon and Jane Goodall’s

It’s one of the greatest stories in science, right up there with Neil Armstrong’s small step on the moon and Jane Goodall’s  Nobody wants to feel helpless or desperate. The days of charities showing people as one-dimensional victims are – hopefully – numbered. Theo Sowa, chief executive of the African Women’s Development Fund, has said: “When people portray us as victims, they don’t want to ask about solutions. Because people don’t ask victims for solutions.”

Nobody wants to feel helpless or desperate. The days of charities showing people as one-dimensional victims are – hopefully – numbered. Theo Sowa, chief executive of the African Women’s Development Fund, has said: “When people portray us as victims, they don’t want to ask about solutions. Because people don’t ask victims for solutions.”