Month: August 2018

Kofi Annan (1938 – 2018)

Fakir Musafar (1930 – 2018)

Call Me Heena: Hijra, The Third Gender

Shahria Sharmin in lensculture:

“I feel like a mermaid. My body tells me that I am a man but my soul tells me that I am a woman. I am like a flower, a flower that is made of paper. I shall always be loved from a distance, never to be touched and no smell to fall in love with.”

—Heena, 51, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012

“Hijra,” a term of South Asia which have no exact match in the modern Western taxonomy of gender, designated as male at birth with feminine gender identity and eventually adopts feminine gender roles. They are often grossly labeled as hermaphrodites, eunuchs, transgender or transsexual women in literature. presently a more justified social term for them is the “Third Gender.” Transcending the biological definition, hijras are a social phenomena as a minority group and have a long recorded history in South Asia. However, their overall social acceptance and present conditions of living vary significantly in countries from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Perhaps the Hijras in Bangladesh face the worst situation, which forces a good number of them to leave their motherland and migrate to India. Instead of coming from various social and family backgrounds, Hijras feel the strongest sense of belonging with their own group—fellow Hijra. These groups give them the shelter of a family and the warmth of human relationship. Outside the group, they are discriminated and scorned almost everywhere. Traditionally, these individuals earned their living based on the cultural belief that Hijras can bless one’s house with prosperity and fertility. Because of the shared geographical and cultural history of the subcontinent, this particular Hindu belief slowly made room in the Muslim culture of this land. Times have changed and Hijras have lost their admired space in the society. Now they make a living by walking around the streets collecting money from shopkeepers, bus and train passengers or through prostitution.

“Hijra,” a term of South Asia which have no exact match in the modern Western taxonomy of gender, designated as male at birth with feminine gender identity and eventually adopts feminine gender roles. They are often grossly labeled as hermaphrodites, eunuchs, transgender or transsexual women in literature. presently a more justified social term for them is the “Third Gender.” Transcending the biological definition, hijras are a social phenomena as a minority group and have a long recorded history in South Asia. However, their overall social acceptance and present conditions of living vary significantly in countries from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Perhaps the Hijras in Bangladesh face the worst situation, which forces a good number of them to leave their motherland and migrate to India. Instead of coming from various social and family backgrounds, Hijras feel the strongest sense of belonging with their own group—fellow Hijra. These groups give them the shelter of a family and the warmth of human relationship. Outside the group, they are discriminated and scorned almost everywhere. Traditionally, these individuals earned their living based on the cultural belief that Hijras can bless one’s house with prosperity and fertility. Because of the shared geographical and cultural history of the subcontinent, this particular Hindu belief slowly made room in the Muslim culture of this land. Times have changed and Hijras have lost their admired space in the society. Now they make a living by walking around the streets collecting money from shopkeepers, bus and train passengers or through prostitution.

I, like almost everyone else in my society, grew up seeing them as less than human. Their habits, way of life, and even looks marked them as different and deviant, as if a living testimony of biological aberration. Then I met Heena, who showed me how wrong I was. She opened her life to me, made me a part of her world and helped me to see something beyond the word “Hijra.” She made me understand her and other members of her community, as the mothers, daughters, friends and lovers that they actually are.

More here.

‘A different way of living’: why writers are celebrating middle-age

Lara Feigel in The Guardian:

When Viv Albertine performs her 2009 song “Confessions of a Milf” live, she alternates between two voices. There’s the saccharine lisp of a brainwashed housewife chanting “home sweet home”, and there’s the raging chant of an angry punk proclaiming that “if you decide one day that you’ve had enough”, you can walk away. Though swans and seahorses mate for life, “we ain’t so nice”. In the 70s, when Albertine performed with her punk band, the Slits, she appeared fully immersed in her performance of exuberant anger, but also strikingly unformed, too busy bouncing and shouting to hold the gaze of her audience. Then, she retained the vulnerability of her younger self, but there was a steeliness underlying it. Now she stares out at us, no longer interested in hiding.

When Viv Albertine performs her 2009 song “Confessions of a Milf” live, she alternates between two voices. There’s the saccharine lisp of a brainwashed housewife chanting “home sweet home”, and there’s the raging chant of an angry punk proclaiming that “if you decide one day that you’ve had enough”, you can walk away. Though swans and seahorses mate for life, “we ain’t so nice”. In the 70s, when Albertine performed with her punk band, the Slits, she appeared fully immersed in her performance of exuberant anger, but also strikingly unformed, too busy bouncing and shouting to hold the gaze of her audience. Then, she retained the vulnerability of her younger self, but there was a steeliness underlying it. Now she stares out at us, no longer interested in hiding.

…In her recent memoir To Throw Away Unopened, Albertine describes deciding to return to music after more than a decade as a housewife, ending her marriage as a result. In the past century of fiction, the middle-aged male protagonist has sprawled and rutted his way to a kind of bathetic greatness in the hands of Philip Roth, John Updike and Saul Bellow. The middle-aged woman has appeared far less often as a protagonist questing for a style and identity, but that is changing fast. Albertine is one of several writers this year to tackle lives that follow divorce and the menopause. Lavinia Greenlaw’s forthcoming novel is a middle-aged love story. Deborah Levy uses the moment of transition from one life to another to fashion a new story about femininity in her “living autobiography” The Cost of Living. Like Albertine’s, Levy’s career began in an era when the young insisted on their own youthfulness. What’s striking is that both writers have found a way to incarnate their middle-aged selves in new voices that don’t reject the spontaneity of punk but reinvent it in a quieter yet no less vigorous form.

More here.

The Conqueror Who Longed for Melons

Mark Hay in Atlas Obscura:

ZAHIR AL-DIN MUHAMMAD, THE 16TH century Central Asian prince better known as Babur, is renowned for his fierce pedigree and proclivities. Descended from both Timur and Genghis Khan, he used military genius to overcome strife and exile, conquer northern India, and found the Moghul dynasty, which endured for over 300 years. He was a warlord who built towers of his enemies’ skulls on at least four occasions. Yet he was also a cultured man who wrote tomes on law and Sufi philosophy, collections of poetry, and a shockingly honest memoir, the Baburnama, in which he appears to us as one of the most complex and human figures of the early modern era.

ZAHIR AL-DIN MUHAMMAD, THE 16TH century Central Asian prince better known as Babur, is renowned for his fierce pedigree and proclivities. Descended from both Timur and Genghis Khan, he used military genius to overcome strife and exile, conquer northern India, and found the Moghul dynasty, which endured for over 300 years. He was a warlord who built towers of his enemies’ skulls on at least four occasions. Yet he was also a cultured man who wrote tomes on law and Sufi philosophy, collections of poetry, and a shockingly honest memoir, the Baburnama, in which he appears to us as one of the most complex and human figures of the early modern era.

Through the Baburnama, we learn that Babur was versed in courtly Persian speech and custom, yet nonetheless a populist who built strong ties with nomads and championed the vernacular Chagatai Turkic tongue in the arts. He was a pious man, but was also given to libertine escapades, including massive, wine-fueled parties.

But the first—and arguably one of the most culturally consequential—personal details he reveals is that he was a food snob.

More here. [Thanks to Farrukh Azfar.]

Cross species transfer of genes has driven evolution

From Phys.org:

Far from just being the product of our parents, University of Adelaide scientists have shown that widespread transfer of genes between species has radically changed the genomes of today’s mammals, and been an important driver of evolution.

Far from just being the product of our parents, University of Adelaide scientists have shown that widespread transfer of genes between species has radically changed the genomes of today’s mammals, and been an important driver of evolution.

In the world’s largest study of so-called “jumping genes”, the researchers have traced two particular jumping genes across 759 species of plants, animals and fungi. These jumping genes are actually small pieces of DNA that can copy themselves throughout a genome and are known as transposable elements.

They have found that cross-species transfers, even between plants and animals, have occurred frequently throughout evolution.

Both of the transposable elements they traced—L1 and BovB—entered mammals as foreign DNA. This is the first time anyone has shown that the L1 element, important in humans, has jumped between species.

More here. [Thanks to Yohan John.]

American Breakdown

David Bromwich in the London Review of Books:

A seasonal report on the Trump presidency had better begin with a disclaimer. Anything one says is sure to be displaced by some entirely unexpected thing the president does between writing and publication. This has happened once already, with the Putin-Trump press briefing in Helsinki and the strange spectacle it afforded: the almost physical manifestation of Trump’s deference to Putin. It may happen again, whether as a result of the volume of sabre-rattling or the onset of war with Iran; a decision to sack Robert Mueller, the special counsel who is investigating meddling in the 2016 election; a shutdown of the federal government to extort funds for the wall with Mexico; a sudden intensification of the president’s attacks on his political enemies and accusers in pending court cases.

A seasonal report on the Trump presidency had better begin with a disclaimer. Anything one says is sure to be displaced by some entirely unexpected thing the president does between writing and publication. This has happened once already, with the Putin-Trump press briefing in Helsinki and the strange spectacle it afforded: the almost physical manifestation of Trump’s deference to Putin. It may happen again, whether as a result of the volume of sabre-rattling or the onset of war with Iran; a decision to sack Robert Mueller, the special counsel who is investigating meddling in the 2016 election; a shutdown of the federal government to extort funds for the wall with Mexico; a sudden intensification of the president’s attacks on his political enemies and accusers in pending court cases.

These eruptions of breaking news are not only possible but certain to occur, because Trump comports himself not as a president or even a politician, but as a reality TV host. He is a showman above all. In a process where the media are cast as reviewers, and voters as spectators, the show is getting bad reviews but doing nicely: the clear sign of success is that nobody can stop talking about the star. He keeps up the suspense with teasers and decoys and unscheduled interruptions, with changes in the sponsors and the supporting cast and production team. The way to match the Trump pace is by tweeting; but that is to play his game – a gambit the White House press corps have found irresistible. Much of the damage to US politics over the last two years has been done by the anti-Trump media themselves, with their mood of perpetual panic and their lack of imagination. But the uncanny gift of Trump is an infectious vulgarity, and with it comes the power to make his enemies act with nearly as little self-restraint as he does. The proof is in the tweets.

More here. [Thanks to Ali Minai.]

Why is Blue So Rare in Nature?

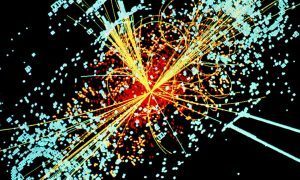

The Consolations of Physics

Graham Farmelo at The Guardian:

Why do wealthy societies spend good money on projects such as this? Higgs bosons and images from the Voyager spacecraft don’t do anything useful and don’t make any of us richer, as Radford acknowledges, though he has no time for such philistinism. His heart and his mind are with the Roman thinker Boethius, who wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, from which Radford takes several of his cues. He stands shoulder to shoulder with Boethius: philosophy can be consoling “even if it is limited to just thinking about thinking”. Beneath his jocularity, Radford is an unapologetic intellectual.

Why do wealthy societies spend good money on projects such as this? Higgs bosons and images from the Voyager spacecraft don’t do anything useful and don’t make any of us richer, as Radford acknowledges, though he has no time for such philistinism. His heart and his mind are with the Roman thinker Boethius, who wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, from which Radford takes several of his cues. He stands shoulder to shoulder with Boethius: philosophy can be consoling “even if it is limited to just thinking about thinking”. Beneath his jocularity, Radford is an unapologetic intellectual.

He glories in telling the remarkable story of the first direct observation of gravitational waves in 2015, almost a century after Einstein foresaw them. A huge team of astronomers detected the waves via a signal that lasted 20 milliseconds and caused a disturbance smaller than a millionth of the width of an atom – a result of two massive black holes merging violently in outer space more than a billion years ago.

more here.

‘The Sparsholt Affair’ by Alan Hollinghurst

J. Daniel Elam at The Quarterly Conversation:

Gossip, speculation, and longing—and the discomfort (and occasional pleasure) of perpetual doubt—are the grounds on which contemporary queer men and women have become used to constructing our genealogies. We possess historical facts enough to fantasize about our “great-grandparents”: the evasive extravagance of Oscar Wilde; the repression with which E.M. Forster asks us to “only connect”; the ambiguity in Djuna Barnes’s famous claim, “I am not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma”; or the half-missing archive of Emma Goldman’s correspondence with women. The following generation of gay men was decimated by a plague, meaning that 30- to 50-year-old gay men will be the first generation to be both openly gay and alive. Even if it is easier now to imagine a queer family of brothers and sisters, it remains much more difficult to imagine a queer lineage. We long for a family tree that never quite appears in full: for queer mothers and fathers that could somehow supplement (or replace) the biological ones whose lives differ so greatly from our own. We construct these families through gossip and speculation, staring at chapter breaks and ellipses until they give us that aunt we might have had. Looking hard enough, we hope, we all might have that aunt.

Gossip, speculation, and longing—and the discomfort (and occasional pleasure) of perpetual doubt—are the grounds on which contemporary queer men and women have become used to constructing our genealogies. We possess historical facts enough to fantasize about our “great-grandparents”: the evasive extravagance of Oscar Wilde; the repression with which E.M. Forster asks us to “only connect”; the ambiguity in Djuna Barnes’s famous claim, “I am not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma”; or the half-missing archive of Emma Goldman’s correspondence with women. The following generation of gay men was decimated by a plague, meaning that 30- to 50-year-old gay men will be the first generation to be both openly gay and alive. Even if it is easier now to imagine a queer family of brothers and sisters, it remains much more difficult to imagine a queer lineage. We long for a family tree that never quite appears in full: for queer mothers and fathers that could somehow supplement (or replace) the biological ones whose lives differ so greatly from our own. We construct these families through gossip and speculation, staring at chapter breaks and ellipses until they give us that aunt we might have had. Looking hard enough, we hope, we all might have that aunt.

more here.

The Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins is Still Ahead of the Times

Seán Hewitt at The New Statesman:

Hopkins is the laureate of “all things counter, original, spare, strange”. He is also, to my mind, the most exquisite English poet of the 19th century. In life, however, he felt the censure not only of his strict Catholicism but also of his own isolation. In one of his late sonnets, he summed up his position as an unpublished – and perhaps unpublishable – poet. A reader unfamiliar with Hopkins’s work will feel immediately the taut difficulty of his language, the force of his sound-scapes, and the miraculous effect of his anthimeria, as in his striking use of “began” as a noun:

Hopkins is the laureate of “all things counter, original, spare, strange”. He is also, to my mind, the most exquisite English poet of the 19th century. In life, however, he felt the censure not only of his strict Catholicism but also of his own isolation. In one of his late sonnets, he summed up his position as an unpublished – and perhaps unpublishable – poet. A reader unfamiliar with Hopkins’s work will feel immediately the taut difficulty of his language, the force of his sound-scapes, and the miraculous effect of his anthimeria, as in his striking use of “began” as a noun:

Only what word Wisest my heart breeds dark heaven’s baffling ban

Bars or hell’s spell thwarts. This to hoard unheard,

Heard unheeded, leaves me a lonely began.

Born in Stratford in Essex (now part of London) in 1844 to deeply religious High Church Anglican parents, Gerard Hopkins (he rarely used the name Manley) was short, fair and slightly built.

more here.

Our loneliness epidemic is a political problem, too

David Masciotra in Salon:

A killer stalks the American street. Its weaponry is subtle, but it is responsible for the demolition of countless lives, and the damage of many communities. After it sneaks into a home, it creates social pathology and helps harvest political cruelty. It is loneliness. The United States of America has created a culture of solitary struggle and isolation. It should not shock too many careful observers who consider the predictable consequences of building an entire civilization on the mud and sewage of cutthroat, competitive corporate capitalism. The true meaning of icy bromides like, “rugged individualism,” “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” and “no free lunch,” is not a celebration of individual freedom as much as it is a “you’re on your own” ethic, or lack thereof, resulting in communal fissure and political friction.

A killer stalks the American street. Its weaponry is subtle, but it is responsible for the demolition of countless lives, and the damage of many communities. After it sneaks into a home, it creates social pathology and helps harvest political cruelty. It is loneliness. The United States of America has created a culture of solitary struggle and isolation. It should not shock too many careful observers who consider the predictable consequences of building an entire civilization on the mud and sewage of cutthroat, competitive corporate capitalism. The true meaning of icy bromides like, “rugged individualism,” “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” and “no free lunch,” is not a celebration of individual freedom as much as it is a “you’re on your own” ethic, or lack thereof, resulting in communal fissure and political friction.

Standards of living the U.S. are generally high, and yet suicide has steadily increased in every state, the homicide rate remains off the charts relative to the rest of the developed world, liver disease from alcohol abuse is on the rise, and opioid overdoses have become so routine in major cities and small towns than many police officers carry, alongside a gun and badge, a dosage of naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of opioid OD. In their bracing and brilliant book, “A General Theory of Love,” psychiatrists Thomas Lewis, Fari Amini, and Richard Lannon put America on the couch, and their diagnosis is rather grim. “A good deal of modern American culture,” they write, “is an extended experiment in the effects of depriving people of what they crave most.”

That which people most crave are the elements and effects of love — hospitality, community, solidarity — a general feeling of belonging and appreciation coupled with the exercise of moral agency for the benefit of other people. Thomas Aquinas defined love as “actively willing the good of the other.”

More here.

No, women aren’t at risk from men

Joanna Williams in Spiked:

Being a feminist must be hard work. Perhaps you’ve got a newspaper column to fill with your hot take on the latest sexist outrage. Or perhaps you have a university sexual-harassment policy to write. Or a government minister to consult about a proposed new law. Or a hefty budget to administer. You’ve got the salary, a platform for your views, and the capacity to influence what happens in almost every institution in the country. And yet the entire basis for you being in this fortunate position, for walking the corridors of power, is your powerlessness. The bind for today’s professional feminist is the more power and influence she gains, the harder she needs to work to show that women are still oppressed.

Being a feminist must be hard work. Perhaps you’ve got a newspaper column to fill with your hot take on the latest sexist outrage. Or perhaps you have a university sexual-harassment policy to write. Or a government minister to consult about a proposed new law. Or a hefty budget to administer. You’ve got the salary, a platform for your views, and the capacity to influence what happens in almost every institution in the country. And yet the entire basis for you being in this fortunate position, for walking the corridors of power, is your powerlessness. The bind for today’s professional feminist is the more power and influence she gains, the harder she needs to work to show that women are still oppressed.

Some career feminists get around this conundrum by claiming they are not representing their own interests but selflessly fighting for other women. Apparently, countless hordes of downtrodden women, unable to speak up for themselves, are just waiting for feminists to give voice to their concerns. But as only a small minority of women identify as feminists (estimates vary between a third and seven per cent), the response to all this speaking on behalf of others seems to be a resounding ‘no thanks’. The last resort of the professional, well-paid, powerful feminist, desperate to prove her credentials as a member of an oppressed group, is to allude to violence. The experience of violence – whether actual, imagined or potential – appears to unite all women, allowing the most privileged to claim common cause with women who are struggling just to get by. Helen Pankhurst, great-granddaughter of Suffragette Emmeline, expresses this succinctly: ‘Violence against women is the one factor that infects every aspect of women’s lives.’

More here.

Hume is the amiable, modest, generous philosopher we need now

Julian Baggini in Aeon:

Socrates died by drinking hemlock, condemned to death by the people of Athens. Albert Camus met his end in a car that wrapped itself around a tree at high speed. Nietzsche collapsed into insanity after weeping over a beaten horse. Posterity loves a tragic end, which is one reason why the cult of David Hume, arguably the greatest philosopher the West has ever produced, never took off.

Socrates died by drinking hemlock, condemned to death by the people of Athens. Albert Camus met his end in a car that wrapped itself around a tree at high speed. Nietzsche collapsed into insanity after weeping over a beaten horse. Posterity loves a tragic end, which is one reason why the cult of David Hume, arguably the greatest philosopher the West has ever produced, never took off.

While Hume was lying aged 65 on his deathbed at the end of a happy, successful and (for the times) long life, he told his doctor: ‘I am dying as fast as my enemies, if I have any, could wish, and as easily and cheerfully as my best friends could desire.’ Three days before he died, on 25 August 1776, probably of abdominal cancer, his doctor could still report that he was ‘quite free from anxiety, impatience, or low spirits, and passes his time very well with the assistance of amusing books’.

When the end came, Dr Black reported that Hume ‘continued to the last perfectly sensible, and free from much pain or feelings of distress. He never dropped the smallest expression of impatience; but when he had occasion to speak to the people about him, always did it with affection and tenderness … He died in such a happy composure of mind, that nothing could exceed it.’

In his own lifetime Hume’s reputation was mainly as a historian. His career as a philosopher started rather inauspiciously.

More here.

A New View of Evolution That Can’t Be Represented by a Tree

Erika Check Hayden in the New York Times:

In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a spindly tree of life in one of his notebooks. Its stick-figure trunk sprouted into four sets of branches. The drawing illustrated his radical idea that, over time, organisms change to give rise to new species.

In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a spindly tree of life in one of his notebooks. Its stick-figure trunk sprouted into four sets of branches. The drawing illustrated his radical idea that, over time, organisms change to give rise to new species.

“I think,” Darwin scrawled, suggestively, above his humble tree.

Biologists have worked since then to fill in the details of that tree. While all beings are related, Darwin intimated, it should be possible to classify all living things into distinct lineages of more closely related species — branches — based on their shared evolutionary histories.

Darwin and others used physical similarities and differences between organisms to add ever more details to his basic tree. Then, after the discovery of DNA’s structure in 1953, scientists began tracing the evolutionary history of life through its shared genetic code.

But that project has now reached a crisis point, David Quammen writes in his new book, “The Tangled Tree.” Genetics is revealing that the branches on Darwin’s tree of life are not so separate from each other as was once thought: Genes sometimes skip from species to unrelated species, effectively fusing different branches together. The big question now is whether Darwin’s tree represents a fundamentally flawed conception of evolutionary history or is merely in need of revision.

More here.

Freedom Requires Limits, So That Others May Enjoy Their Freedom Too

Namit Arora in Outlook:

Freedom is the ability to pursue the life one values. This view of freedom is inclusive, open-ended, and flexible. It embraces our plural, evolving, and diverse conceptions of the good life. It also admits other long-standing ideas of freedom, such as not being held in servitude, possessing political self-rule, or enjoying the right to act, speak, and think as one desires.

Freedom is the ability to pursue the life one values. This view of freedom is inclusive, open-ended, and flexible. It embraces our plural, evolving, and diverse conceptions of the good life. It also admits other long-standing ideas of freedom, such as not being held in servitude, possessing political self-rule, or enjoying the right to act, speak, and think as one desires.

Some people naively equate freedom with an absence of social restraints. But should I be free to do whatever I want? Should I be free to pollute the river, not pay any taxes, or torture the cat? To play loud music on the metro, not rent my apartment to Dalits, or incite hate or violence against other groups? I hope not. My freedom requires limits, so that others may enjoy their freedom. Edmund Burke held that freedom must be limited in order to be possessed. A freer society is not necessarily one with fewer social restraints, but one with a wisely chosen set of restraints and provisions, such as public education, healthcare, and ample safety nets for all.

But inevitably, in pursuing the life we value, we’ll sometimes run into strong disagreements over our values and the restraints and provisions we see as conducive to freedom. These disagreements might spring from our religious vs. secular values, modern vs. traditional values, egalitarian vs. libertarian values, authoritarian vs. democratic values, and various other axes of identity, culture, and belief.

More here.

Steven Pinker: Is the world getting better or worse?

Congo and Colonialism

Angus Mitchell at The Dublin Review of Books:

As the nineteenth century came to an end, rumours started to circulate widely about the violence perpetrated by the regime of King Leopold II in the Congo Free State. Parliamentary intervention followed from involvement by the two main NGOs: the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and the Aborigines Protection Society. In 1903, a question was asked in the House of Commons by the Liberal MP Herbert Samuel. The foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne, ordered the British consul and his man on the spot, Roger Casement, to journey into the upper Congo. Having spent five years reporting officially on many aspects of Leopold’s colonial administration, Casement was well-placed to investigate the stories. He would spend the next three months travelling through the region. On exiting the river with a dossier of hand-written reports, copied correspondences and memos, testimonies and a diary, he scribbled the first of nearly three hundred letters to ED Morel, a young activist-writer. He recommended him to read Heart of Darkness and suggested he contact the author, Joseph Conrad, to see if he would support a public campaign for systemic reform. Casement and Conrad had met in the lower Congo in 1890 and a friendship had developed between the two men.

As the nineteenth century came to an end, rumours started to circulate widely about the violence perpetrated by the regime of King Leopold II in the Congo Free State. Parliamentary intervention followed from involvement by the two main NGOs: the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and the Aborigines Protection Society. In 1903, a question was asked in the House of Commons by the Liberal MP Herbert Samuel. The foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne, ordered the British consul and his man on the spot, Roger Casement, to journey into the upper Congo. Having spent five years reporting officially on many aspects of Leopold’s colonial administration, Casement was well-placed to investigate the stories. He would spend the next three months travelling through the region. On exiting the river with a dossier of hand-written reports, copied correspondences and memos, testimonies and a diary, he scribbled the first of nearly three hundred letters to ED Morel, a young activist-writer. He recommended him to read Heart of Darkness and suggested he contact the author, Joseph Conrad, to see if he would support a public campaign for systemic reform. Casement and Conrad had met in the lower Congo in 1890 and a friendship had developed between the two men.

more here.

In V.S. Naipaul’s Writing on Conrad, We See Who He Truly Is

Something I wrote on Naipaul a few years ago, which I post now as a kind of memorial… It was published in The Smart Set April, 2015:

The fact is, Naipaul provides powerful ammunition for all sides of the debate. Were Naipaul simply a monster, he (and his writing) would not be so compelling. Revealing himself to be a monster in one instance, he will use that very quality to his own advantage in the next. This protean quality makes Naipaul larger, as a character, a novelist, and a thinker, than any of the categories meant to encompass him. Those, for instance, who want to dismiss Naipaul for what Wood calls his “conservatism”, find themselves, more often than not, moved by his “radical eyesight.” And vice versa. Inevitably, to read Naipaul is to experience a rather exciting push/pull of attraction and repulsion. You can see this even in the short quote from Packer’s review of the French biography above. Naipaul describes extremely ugly behavior. Further, he seems to take narcissistic pleasure (the word ‘narcissism’ comes up often in discussions of Naipaul) in doing so. But he ends with a thought that is sensitive and vulnerable. “I was utterly helpless. I have enormous sympathy for people who do strange things out of passion.” By turning his sympathy around, he elicits it from us.

The fact is, Naipaul provides powerful ammunition for all sides of the debate. Were Naipaul simply a monster, he (and his writing) would not be so compelling. Revealing himself to be a monster in one instance, he will use that very quality to his own advantage in the next. This protean quality makes Naipaul larger, as a character, a novelist, and a thinker, than any of the categories meant to encompass him. Those, for instance, who want to dismiss Naipaul for what Wood calls his “conservatism”, find themselves, more often than not, moved by his “radical eyesight.” And vice versa. Inevitably, to read Naipaul is to experience a rather exciting push/pull of attraction and repulsion. You can see this even in the short quote from Packer’s review of the French biography above. Naipaul describes extremely ugly behavior. Further, he seems to take narcissistic pleasure (the word ‘narcissism’ comes up often in discussions of Naipaul) in doing so. But he ends with a thought that is sensitive and vulnerable. “I was utterly helpless. I have enormous sympathy for people who do strange things out of passion.” By turning his sympathy around, he elicits it from us.

more here.