Sudip Bose at The American Scholar:

Not long ago, Turner Classic Movies aired several episodes of the 1950s television show Omnibus in which that most engaging and passionate of teachers, Leonard Bernstein, aided by singers and instrumentalists, lectured on various musical subjects. The aim of Omnibus was to enrich the cultural life of the American public, and as such, it represented an early attempt at producing programming that was entertaining as well as educational. If you had tuned in to those Sunday afternoon and evening shows, you might have encountered the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright or William Saroyan or Orson Welles. Bernstein hosted seven programs (forerunners to his legendary Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic), which covered topics such as “What Makes Opera Grand,” “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” and “The American Musical Comedy”—their illuminating content belying these somewhat sober titles. I happened upon the Bernstein mini-marathon when it was halfway over, though I did manage to add a few episodes to my DVR queue. A few evenings ago, I happily settled in to watch “The Music of J. S. Bach”—the most inspiring hour I’ve spent in front of the television in ages.

Not long ago, Turner Classic Movies aired several episodes of the 1950s television show Omnibus in which that most engaging and passionate of teachers, Leonard Bernstein, aided by singers and instrumentalists, lectured on various musical subjects. The aim of Omnibus was to enrich the cultural life of the American public, and as such, it represented an early attempt at producing programming that was entertaining as well as educational. If you had tuned in to those Sunday afternoon and evening shows, you might have encountered the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright or William Saroyan or Orson Welles. Bernstein hosted seven programs (forerunners to his legendary Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic), which covered topics such as “What Makes Opera Grand,” “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” and “The American Musical Comedy”—their illuminating content belying these somewhat sober titles. I happened upon the Bernstein mini-marathon when it was halfway over, though I did manage to add a few episodes to my DVR queue. A few evenings ago, I happily settled in to watch “The Music of J. S. Bach”—the most inspiring hour I’ve spent in front of the television in ages.

more here.

The eternal challenge is to answer grief with something that resembles love. To choose not just to sit around decrying hardship and injustice but instead to uncurl your fists and approach sorrow with grace, power, and, most incredibly, gratitude—not for the hurt itself but for the whole miraculous mess of being alive, this strange endowment of breath and blood. Most days, I believe that

The eternal challenge is to answer grief with something that resembles love. To choose not just to sit around decrying hardship and injustice but instead to uncurl your fists and approach sorrow with grace, power, and, most incredibly, gratitude—not for the hurt itself but for the whole miraculous mess of being alive, this strange endowment of breath and blood. Most days, I believe that  A bit more than 8000 years ago, the world suddenly cooled, leading to much drier summers for much of the Northern Hemisphere. The impact on early farmers must have been extreme, yet archaeologists know little about how they endured. Now, the remains of animal fat on broken pottery from one of the world’s oldest and most unusual protocities—known as Çatalhöyük—is finally giving scientists a window into these ancient peoples’ close call with catastrophe. “I think the authors have done an excellent job,” says John Marston, an environmental archaeologist at Boston University who wasn’t involved in the current study. “It shows the people of Çatalhöyük were incredibly resilient.” Today, Çatalhöyük is just a series of dusty, sun-baked ruins in central Turkey. But thousands of years ago it was a bustling prehistoric metropolis. From about 7500 B.C.E to 5700 B.C.E., early farmers grew wheat, barley, and peas, and raised sheep, goats, and cattle. At its height, some 10,000 people lived there. Among its more noteworthy features, Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants were

A bit more than 8000 years ago, the world suddenly cooled, leading to much drier summers for much of the Northern Hemisphere. The impact on early farmers must have been extreme, yet archaeologists know little about how they endured. Now, the remains of animal fat on broken pottery from one of the world’s oldest and most unusual protocities—known as Çatalhöyük—is finally giving scientists a window into these ancient peoples’ close call with catastrophe. “I think the authors have done an excellent job,” says John Marston, an environmental archaeologist at Boston University who wasn’t involved in the current study. “It shows the people of Çatalhöyük were incredibly resilient.” Today, Çatalhöyük is just a series of dusty, sun-baked ruins in central Turkey. But thousands of years ago it was a bustling prehistoric metropolis. From about 7500 B.C.E to 5700 B.C.E., early farmers grew wheat, barley, and peas, and raised sheep, goats, and cattle. At its height, some 10,000 people lived there. Among its more noteworthy features, Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants were  Vijay Prashad in The Hindu:

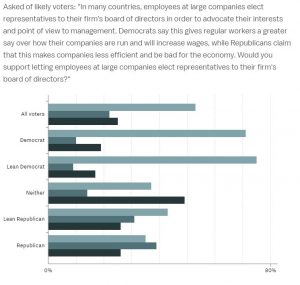

Vijay Prashad in The Hindu: Matthew Yglesias in Vox:

Matthew Yglesias in Vox: Grafton Tanner in The LA Review of Books:

Grafton Tanner in The LA Review of Books: Forty-five years after his death, Pablo Neruda’s poetry still has the power to astonish and appall, awaken and chill us and leave us shaking our heads in bafflement or respect. There is such breadth and profligate intelligence in the work, which ranges from opaque surrealism to bighearted populism to Pan-American epic to shocking propaganda, that one hardly knows where to place it in our era of thwarted emotions. Clearly it is not of our time. Given Neruda’s relations with women, it is certainly not of the time of #MeToo. The work will not always sit well beside a mature feminist consciousness, and of course it will not please ideologues who can’t tell one form of socialism from another. Neruda changed, and his circumstances changed. As a man he could be a monster of egotism and a courageous dissident, a purblind Stalinist and a Roosevelt democrat. His poetry incarnates these shifts and siftings and restless experiments. The past is a moving target. Poetry keeps it alive.

Forty-five years after his death, Pablo Neruda’s poetry still has the power to astonish and appall, awaken and chill us and leave us shaking our heads in bafflement or respect. There is such breadth and profligate intelligence in the work, which ranges from opaque surrealism to bighearted populism to Pan-American epic to shocking propaganda, that one hardly knows where to place it in our era of thwarted emotions. Clearly it is not of our time. Given Neruda’s relations with women, it is certainly not of the time of #MeToo. The work will not always sit well beside a mature feminist consciousness, and of course it will not please ideologues who can’t tell one form of socialism from another. Neruda changed, and his circumstances changed. As a man he could be a monster of egotism and a courageous dissident, a purblind Stalinist and a Roosevelt democrat. His poetry incarnates these shifts and siftings and restless experiments. The past is a moving target. Poetry keeps it alive. Susan Carlile explains with good judgement in her introduction why it is time for a new, full, critical biography of Charlotte Lennox, who, along with Eliza Haywood in particular, acts as a linking presence between the Aphra Behn-inflected, rackety experiments of Delariviere Manley, in the early eighteenth century, and the more solidly respectable achievements of Austen and Frances Burney. This biography, “the first to consider Lennox’s entire oeuvre and all her extant correspondence”, gives the fullest account of her life yet (following pioneering work by Miriam Small, Gustavus Maynardier and Philippe Séjourné), and conducts readers through all of her major works. It arrives as a handsome, substantial volume, complete with full scholarly apparatus and a proselytizing zeal of application that is both good to see and a little perplexing in tenor: Lennox is simultaneously “representative and exceptional, innovative and illustrative”. Lennox did have an “independent mind”, in whatever degree this was possible as one negotiated the path to Grub Street solvency, and Carlile was right to make this the book’s subtitle and leitmotif, rather than giving Lennox the “dangerous” or “powerful” mind she initially considered.

Susan Carlile explains with good judgement in her introduction why it is time for a new, full, critical biography of Charlotte Lennox, who, along with Eliza Haywood in particular, acts as a linking presence between the Aphra Behn-inflected, rackety experiments of Delariviere Manley, in the early eighteenth century, and the more solidly respectable achievements of Austen and Frances Burney. This biography, “the first to consider Lennox’s entire oeuvre and all her extant correspondence”, gives the fullest account of her life yet (following pioneering work by Miriam Small, Gustavus Maynardier and Philippe Séjourné), and conducts readers through all of her major works. It arrives as a handsome, substantial volume, complete with full scholarly apparatus and a proselytizing zeal of application that is both good to see and a little perplexing in tenor: Lennox is simultaneously “representative and exceptional, innovative and illustrative”. Lennox did have an “independent mind”, in whatever degree this was possible as one negotiated the path to Grub Street solvency, and Carlile was right to make this the book’s subtitle and leitmotif, rather than giving Lennox the “dangerous” or “powerful” mind she initially considered. For the burgeoning fields of environmental humanities, it has long since become a commonplace notion that there isn’t really any such thing as “nature” or “wilderness”: both words used to connote real places—pristine and untouched places—but with the increasing knowledge that such a state of being likely never existed, the words come up empty. There are, however, new narratives: Through a case study of the global matsutake mushroom trade, anthropologist Anna Tsing shows compellingly in

For the burgeoning fields of environmental humanities, it has long since become a commonplace notion that there isn’t really any such thing as “nature” or “wilderness”: both words used to connote real places—pristine and untouched places—but with the increasing knowledge that such a state of being likely never existed, the words come up empty. There are, however, new narratives: Through a case study of the global matsutake mushroom trade, anthropologist Anna Tsing shows compellingly in  Yuval Noah Harari’s

Yuval Noah Harari’s When Kathleen Morrison stepped onto the stage to present her research on the effects of stress on the brains of mothers and infants, she was nearly seven and a half months pregnant. The convergence was not lost on Morrison, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, nor on her audience. If there ever was a group of scientists that would be both interested in her findings and unphased by her late-stage pregnancy, it was this one. Nearly 90 percent were women. It is uncommon for any field of science to be dominated by women. In 2015, women received only 34.4 percent of all STEM degrees.1 Even though women now earn more than half of PhDs in biology-related disciplines, only 36 percent of assistant professors and 18 percent of full professors in biology-related fields are women.2 Yet, 70 percent of the speakers at this year’s meeting of the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences (OSSD), where Morrison spoke, were women. Women make up 67 percent of the regular members and 81 percent of trainee members of OSSD, which was founded by the Society for Women’s Health Research. Similarly, 68 percent of the speakers at the annual meeting of the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology (SBN) in 2017 were women. In the field of behavioral neuroendocrinology, 58 percent of professors and 62 percent of student trainees are women. The leadership of both societies also skews female, and the current and recent past presidents of both societies are women.

When Kathleen Morrison stepped onto the stage to present her research on the effects of stress on the brains of mothers and infants, she was nearly seven and a half months pregnant. The convergence was not lost on Morrison, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, nor on her audience. If there ever was a group of scientists that would be both interested in her findings and unphased by her late-stage pregnancy, it was this one. Nearly 90 percent were women. It is uncommon for any field of science to be dominated by women. In 2015, women received only 34.4 percent of all STEM degrees.1 Even though women now earn more than half of PhDs in biology-related disciplines, only 36 percent of assistant professors and 18 percent of full professors in biology-related fields are women.2 Yet, 70 percent of the speakers at this year’s meeting of the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences (OSSD), where Morrison spoke, were women. Women make up 67 percent of the regular members and 81 percent of trainee members of OSSD, which was founded by the Society for Women’s Health Research. Similarly, 68 percent of the speakers at the annual meeting of the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology (SBN) in 2017 were women. In the field of behavioral neuroendocrinology, 58 percent of professors and 62 percent of student trainees are women. The leadership of both societies also skews female, and the current and recent past presidents of both societies are women. The left has an obvious and pressing need to unperson him; what he and the other members of the so-called “

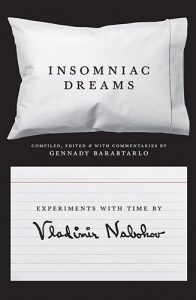

The left has an obvious and pressing need to unperson him; what he and the other members of the so-called “ The authorship of Insomniac Dreams is surprisingly ambiguous. Yes, it contains the unpublished dream diary of Vladimir Nabokov – but that takes up just over sixty pages of a two hundred-odd page book. So what about the rest? The cover gives some indication. ‘Experiments with Time by Vladimir Nabokov’ is displayed on an index card – Nabokov’s favourite piece of stationery – that sits beneath a big white pillow emblazoned with the book’s title. Nabokov’s name is printed as a reproduction of his signature, as if the cover’s index card had been signed by Nabokov himself. And in a way it was; in its archival form, the dream diary consists of 118 index cards on which Nabokov recorded his dreams over about eighty days – from 14 October 1964 to 3 January 1965. Nestled modestly between the card and the pillow is the crux of the ambiguity – ‘Compiled, edited & with commentaries by Gennady Barabtarlo’.

The authorship of Insomniac Dreams is surprisingly ambiguous. Yes, it contains the unpublished dream diary of Vladimir Nabokov – but that takes up just over sixty pages of a two hundred-odd page book. So what about the rest? The cover gives some indication. ‘Experiments with Time by Vladimir Nabokov’ is displayed on an index card – Nabokov’s favourite piece of stationery – that sits beneath a big white pillow emblazoned with the book’s title. Nabokov’s name is printed as a reproduction of his signature, as if the cover’s index card had been signed by Nabokov himself. And in a way it was; in its archival form, the dream diary consists of 118 index cards on which Nabokov recorded his dreams over about eighty days – from 14 October 1964 to 3 January 1965. Nestled modestly between the card and the pillow is the crux of the ambiguity – ‘Compiled, edited & with commentaries by Gennady Barabtarlo’. IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY

IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY Framed as a book of ‘lessons’, his new work seems obviously inspired by such bestsellers as Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life. In the acknowledgements, he explains that he wrote it ‘in conversation with the public’, since many of the chapters originated in answer to ‘questions I was asked by readers, journalists and colleagues’. If somebody asks Harari a question, and he then gives a 5,000-word answer, does that genuinely count as a ‘conversation’? In any case, it would surely be more accurate, as well as less pretentious, to describe it as a compilation of previously published articles, many of which appeared in the Financial Times and The Guardian and on Bloomberg View.

Framed as a book of ‘lessons’, his new work seems obviously inspired by such bestsellers as Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life. In the acknowledgements, he explains that he wrote it ‘in conversation with the public’, since many of the chapters originated in answer to ‘questions I was asked by readers, journalists and colleagues’. If somebody asks Harari a question, and he then gives a 5,000-word answer, does that genuinely count as a ‘conversation’? In any case, it would surely be more accurate, as well as less pretentious, to describe it as a compilation of previously published articles, many of which appeared in the Financial Times and The Guardian and on Bloomberg View. Elephants are one of nature’s biggest improbabilities—literally. Their colossal bodies somehow manage to defy the odds: Despite the fact that their cells outnumber humans’ by a factor of

Elephants are one of nature’s biggest improbabilities—literally. Their colossal bodies somehow manage to defy the odds: Despite the fact that their cells outnumber humans’ by a factor of  On October 10, 1953, V.S. Naipaul sent a telegram home to his family in Trinidad. At that time,

On October 10, 1953, V.S. Naipaul sent a telegram home to his family in Trinidad. At that time,