by Emily Ogden

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

—Thomas Hardy, “The Darkling Thrush,” 1900

The year and the century are dying; everything else is already dead. In Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” (1900), it is a dim day in the dimmest part of the year. Sunset will come early; night in Dorset, England, where Hardy lived, will last sixteen hours. A thrush sings, unwarrantably, of “joy illimited.” Why in the world? Or is his reason not of this world? Is he better informed than we? May we hope? Hardy’s subject is the close relationship between our own ignorance and our belief in another’s knowledge. To realize that we don’t know something is to realize that someone else might. To think that what the other knows might be good, might even be divine good, in spite of the earth’s sorry state—well, that is to celebrate Christmas.

“The Darkling Thrush” was first published on December 29, 1900, under the title “By the Century’s Deathbed.” There is a horticultural term for the season Hardy was then living at his house in Dorset, and that we in the Northern hemisphere are living now: the Persephone Days, named for the goddess of spring’s annual rape at Hades’ hands. You are in the Persephone Days, according to gardener Eliot Coleman, when fewer than ten of the twenty-four hours are light. Why ten hours? Because vegetables mostly slow or stop their growth with any less. “The ancient pulse of germ and birth / [is] shrunken hard and dry,” as Hardy wrote. Plenty of vegetables are cold tolerant. I have kale plants in my front yard now that can withstand a 10º F night. Darkness, however, stunts them. The problem winter poses for our survival is not the freezing of water. It’s the freezing of time. I’ll eat only what reaches maturity before the annual darkness comes.

Or I can always go to Whole Foods. Shopping and other glamours flurry about in the foreground these dark days, distracting us from Sol’s deadly swing toward Capricorn. Black Friday roughly coincides with the start of the Persephone Days; in Norfolk, Virginia (36.8º N latitude), they coincide exactly. Black Friday is itself a kind of heretical outgrowth from Advent, a time of holy anticipation; some of us confusedly observe them both by receiving toy catalogs, letting ourselves buy cheese balls from festive displays, and growing tired of ecstatic carolings. Call it Advert. If you were in America four weeks ago, you may have found the retail festival the most noticeable of the three, followed by the liturgical holiday, with the horticultural one coming in a distant third, if at all. But that’s the whole point of the first two: to be noticeable. So as not to notice the other thing. The very intensity of the annual danse macabre shows we have not entirely forgotten our fear of the dark. Read more »

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case. Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.  Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain. Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

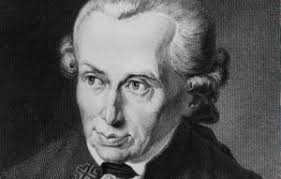

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea. In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.