by Paul Braterman

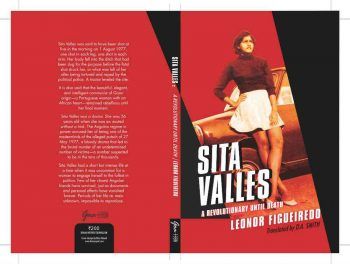

20th-century creationism and racism

Henry Morris, founding father of modern Young Earth creationism, wrote in 1977 that the Hamitic races (including red, yellow, and black) were destined by their nature to be servants to the descendants of Shem and Japheth. Noah was inspired when he prophesied this (Genesis 9:25-27) [1]. The descendants of Shem are characterised by an inherited religious zeal, those of Japheth by mental acumen, while those of Ham are limited by the “peculiarly concrete and materialistic thought-structure inherent in Hamitic peoples,” which even affects their language structures. These innate differences explain the success of the European and Middle Eastern empires, as well as African servitude.

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

Morris is no fringe figure. On the contrary, he, more than any other individual, was responsible for the 20th-century invention of Young Earth “creation science”. He was co-author of The Genesis Flood, which regards Noah’s flood as responsible for sediments worldwide, and founded the Institute of Creation Research (of which Answers in Genesis is a later offshoot) in 1972, serving as its President, and then President Emeritus, until his death in 2006.

Nor was this a personal aberration. As we shall see, he was heir to a strong tradition of creationist racism, of which he never managed to rid himself.

Strong accusations require strong evidence. I have therefore included as an Appendix some relevant passages from The Beginning of the World, quoting at length to avoid any risk of misrepresentation. Read more »

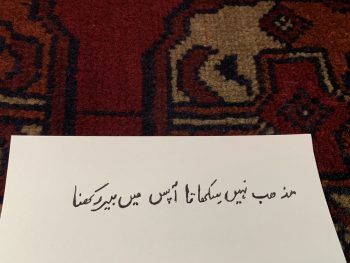

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

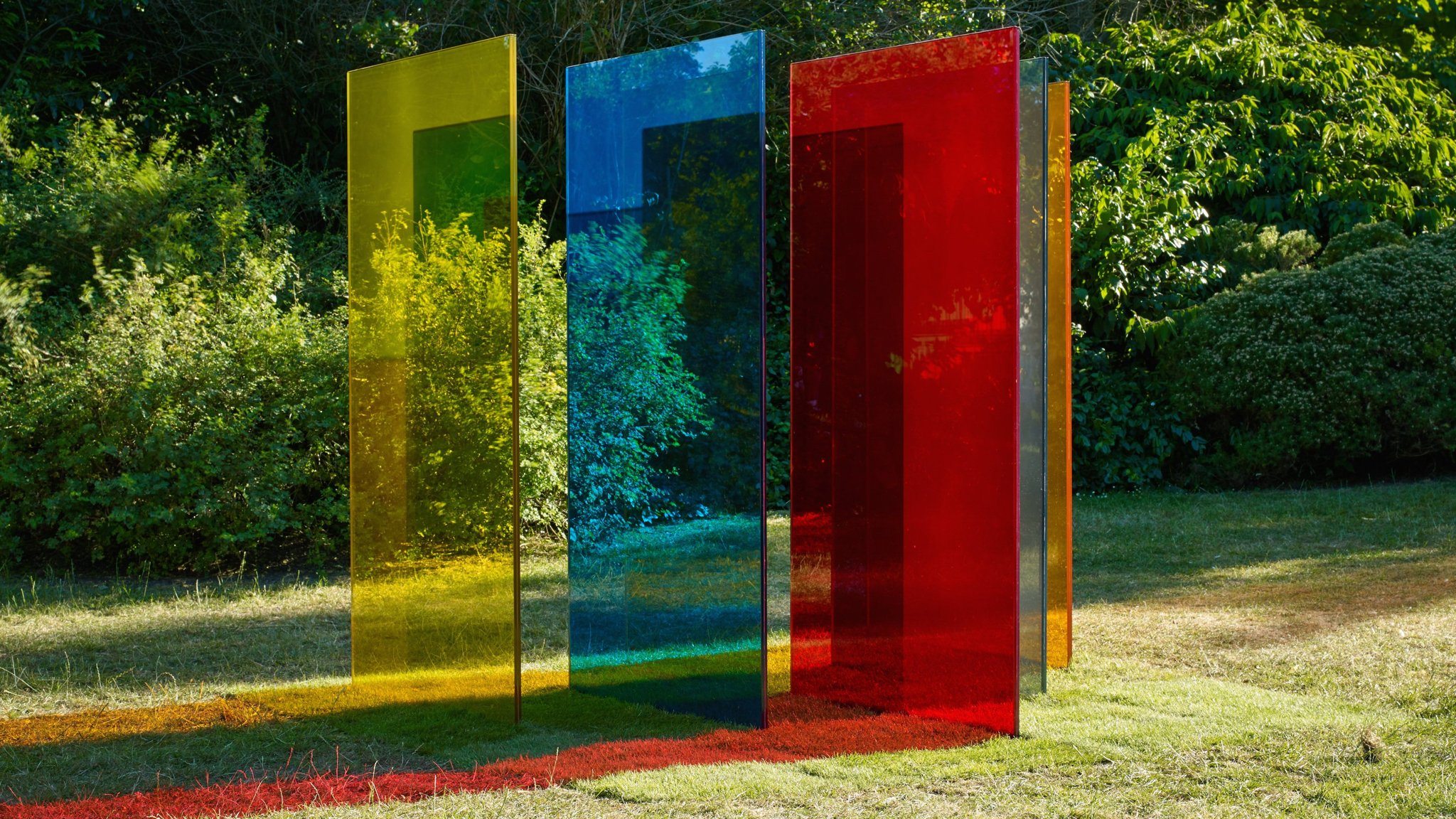

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.)

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.) I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students.

I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students. “…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

“…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”