by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

In 1973 Betty Friedan traveled to France to have a conversation about the state of feminism with Simone de Beauvoir, whom she regarded as a cultural hero. Friedan’s own opinions had evolved considerably in the decade since the publication of The Feminine Mystique. She would elaborate those changes sometime later in a new book, The Second Stage, in which she argued for women’s work in the home to be viewed as “real work” and included in the gross national product. Now, in her meeting with Beauvoir, Friedan asked her opinion on ways to recognize the value of that work, such as crediting it for social security purposes, or distributing vouchers which parents could either use to buy childcare or collect on themselves as full-time caregivers. Perhaps Friedan wondered if Beauvoir’s thinking too might have changed since she stated in The Second Sex that the work of a woman at home “is not directly useful to society, it does not open out on the future, it produces nothing.” If so, she got her answer: Beauvoir, holding out for a total remake of society, believed that even in the meantime “No woman should be authorized to stay at home to raise her children …. Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make that one.”

Rhetoric is one thing, and given the many ideological variations within the women’s movement, any attempt to attribute to it some particular position on women’s work in the home would almost certainly invite fierce disagreement. But it is much harder to dispute what has actually happened in the last half-century. In certain respects the women’s movement has had enormous success. Women’s levels of education, employment, and income have all surged. In that sense the situations of men and women are far more alike than they once were. Through their inroads into realms previously closed to them, women have obtained a share of the status which was once conferred far more heavily on men.

I would be hard-pressed to say, though, that there has been any improvement in the status of “women’s work.” (I mean by that the traditional work of women, whether performed by women or by men.) The essential functions without which no society can exist – the care of children, the preparation of food, the keeping of a house, the care of the elderly and infirm – continue to be devalued. Read more »

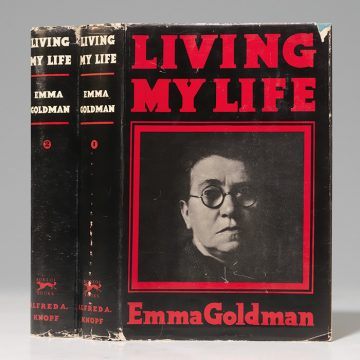

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

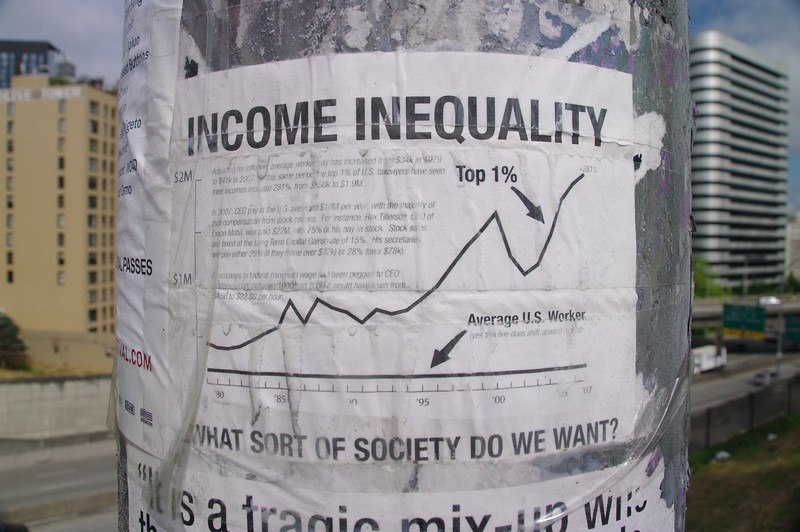

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life. There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “ Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside.

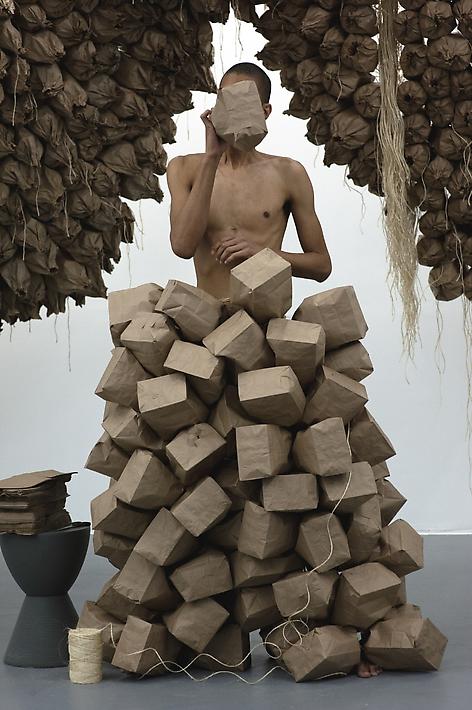

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside. Trapped

Trapped