by Eric J. Weiner

The word “schlep” comes from the Yiddish “schlepn,” which means to drag or haul. You don’t have to be Jewish to be a schlepper, although it couldn’t hurt. Amidst the deepening economic and political inequities informing everyday life, schlepping is one of the great social equalizers. To see a person in the subway or on the street, schlepless as it were, can be a bit disorienting. Who is this person who can travel so unencumbered? He (and it’s almost always a “he”) must be wealthy and powerful beyond imagination: A king or prince? A tech-guru? A hip-hop mogul? A cannabis hedge fund manager? Maybe he’s a mysterious, self-identified “founder” flush with new money and the freedom from schlepping it buys. Maybe he has “people” to schlep for him. They must be “professional” schleppers undoubtedly paid below a living-wage to schlep things they could never afford to schlep themselves.

Yet at the same time, I look upon this extravagantly empty-handed man-king with a degree of benevolent pity. Nothing to schlep must make traveling through the world an empty, meaningless experience. Absent the things he doesn’t carry how would he know not only where he is but who he is? It is true that we may be more than the sum total of what we schlep, but take away the stuff we schlep and it becomes difficult to know where the measure of who and where we are even begins.

Providing the theoretical and methodological foundation for such an analysis of the things we schlep, Stuart Hall’s (1997) seminal analysis of the Sony Walkman articulates the things people schlep to a general theory of culture itself. For Hall, the things we schlep represent a kind of language and as a consequence the study of cultural artifacts hold enormous promise in helping us understand complex systems of representation, meaning and power. Read more »

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the  The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”  are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given. These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya.

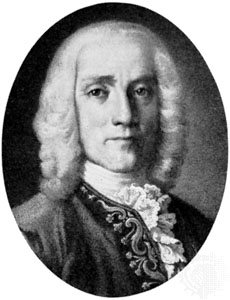

These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya. Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the