by Denis Robinson

Some philosophers I know seem to be engaging in a “this is what I work on in no long words” meme game. I’m retired and I don’t think I could have done it anyway. But in 2005 there was a wee game of that ilk, in which the aim was just to write some philosophy in words of one syllable. I wrote some thoughts I had had: short words but a long piece. I’ve taken this opportunity to make a couple of improvements I’ve long thought of. Here is the whole thing:

Some say it’s all just text and what it means must be as may be, no neat or sharp thoughts or claims which mean just what they say, no grand tales we can know to be true, just a mix of words which shift as we look at them or speak them or hear them some way or not, say “yes” or “no” to them, or play our word games with them just as we play our life games, fight our word wars with them as we fight our life wars, and so on and on and all this and that. If it takes text to say what text means, and then yet more text to say what that text means, and so on, how can it end but in text? At least in France.

But I say this. You can think of words as like tools.

So let’s think of tools for a bit. Stone age folks had a few rough tools, which would do a few rough jobs – split a rock, or a tree, or a skull, crush a nut, spear or skin a fish or a deer, store an egg or some seeds, light a fire, but all no more than fair for what few things they had to do. You might think a lot of rough tools could just make more rough tools at best. Not so. We now have lots of good fine sharp tools, which cut and draw and rule straight and true, we can make a neat screw bolt with a nut to fit tight on it, we can weigh a small wee bit of an ounce or a gram, we can build a plane or a ship or a great big house or mall or hall or bridge, we can see things much too small for the eye to see on its own, we can make small hard drives which store gigs and gigs of stuff, we can surf the net and phone some place on the far side of the world while still on line. We have tools which each do their own jobs well, just as we wish them to, more or less, and each new lot of tools lets us make the next lot yet more fine and use them for yet more things.

I say, so it went with words. It may be that once we had just rough blunt words as tools to speak our speech and think our thoughts. It may be that back then our thoughts, or at least our words and what they meant, were vague, not clear, a mix, like things seen in dreams. Our words would not add all that much to our ways of life, just help us share a bit, work a bit, play a bit, each with each, but all vague, each like a broad dim patch, not a bright spot or dot in the great field of things we might think or mean. But just as you can start with blunt tools and make tools that are sharp, you can start with dim thoughts and make thoughts that are clear, start with vague words and make words that mean things sharp and true, words that do well to state just what you mean and such that each one who knows those words knows what you mean when you say them. Read more »

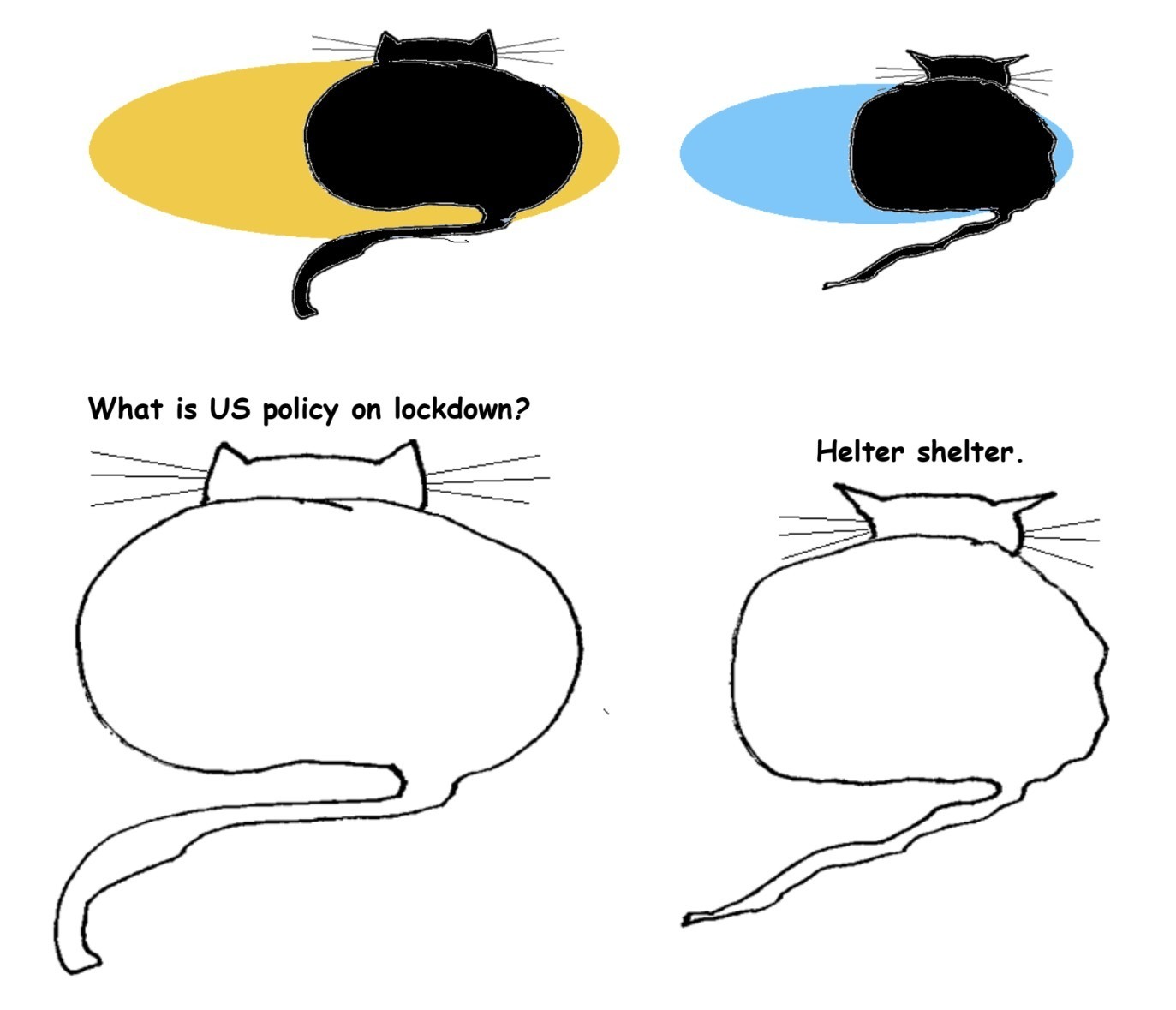

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that  Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality.

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality. The month of Ramadan is at once a time of respite from the external— when one’s focus shifts from worldly affairs to the spiritual— and a time to deepen one’s sense of compassion and fellow-feeling via the rigors of daily fasting, prayer, reflection and generous giving. It is a time to break free from day to day concerns and to pay attention to one’s lifelong inner journey, whether it is through revitalizing the connection with the Divine or investing in human relations: personal, communal, and global.

The month of Ramadan is at once a time of respite from the external— when one’s focus shifts from worldly affairs to the spiritual— and a time to deepen one’s sense of compassion and fellow-feeling via the rigors of daily fasting, prayer, reflection and generous giving. It is a time to break free from day to day concerns and to pay attention to one’s lifelong inner journey, whether it is through revitalizing the connection with the Divine or investing in human relations: personal, communal, and global.

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated talk of the systemic- or societal relevance of institutions and professions. Quickly, attributions of systemic relevance have become a matter of distribution of resources. In Germany, for example,

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated talk of the systemic- or societal relevance of institutions and professions. Quickly, attributions of systemic relevance have become a matter of distribution of resources. In Germany, for example,  What is worse – coronavirus itself, or the social and economic catastrophe that comes with it?

What is worse – coronavirus itself, or the social and economic catastrophe that comes with it? Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague.

Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague. What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.