by Charlie Huenemann

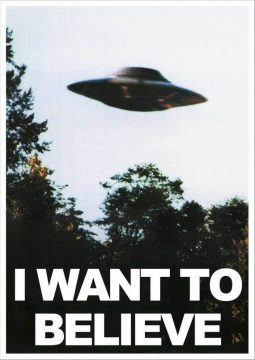

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

Descartes was scrupulous about this distinction as he inched his way through the Meditations, continually asking himself what he was really experiencing, as opposed to the judgments he was making about the experience. Do I experience my hands? Or do I only experience the visual and tactile data suggesting that I have hands? Can I infer the existence of the material world from what I experience, or are there other ways of interpreting the sensations that do not suppose there is an external world? Evil genius, anyone? Brain in a vat?

It’s this line of thought that led some philosophers to postulate sense data, or private mental packets of experience whose esse is their percipi, meaning that they don’t exist as anything other than sensations. You see the flower in the vase; I do too, but since I’m across the table from you, my sensations are different in some ways. The colors are the same, or close to the same, but the arrangement is different because of our different perspectives. Different perspectives yield different sets of sense data; that’s what makes them different perspectives. Read more »

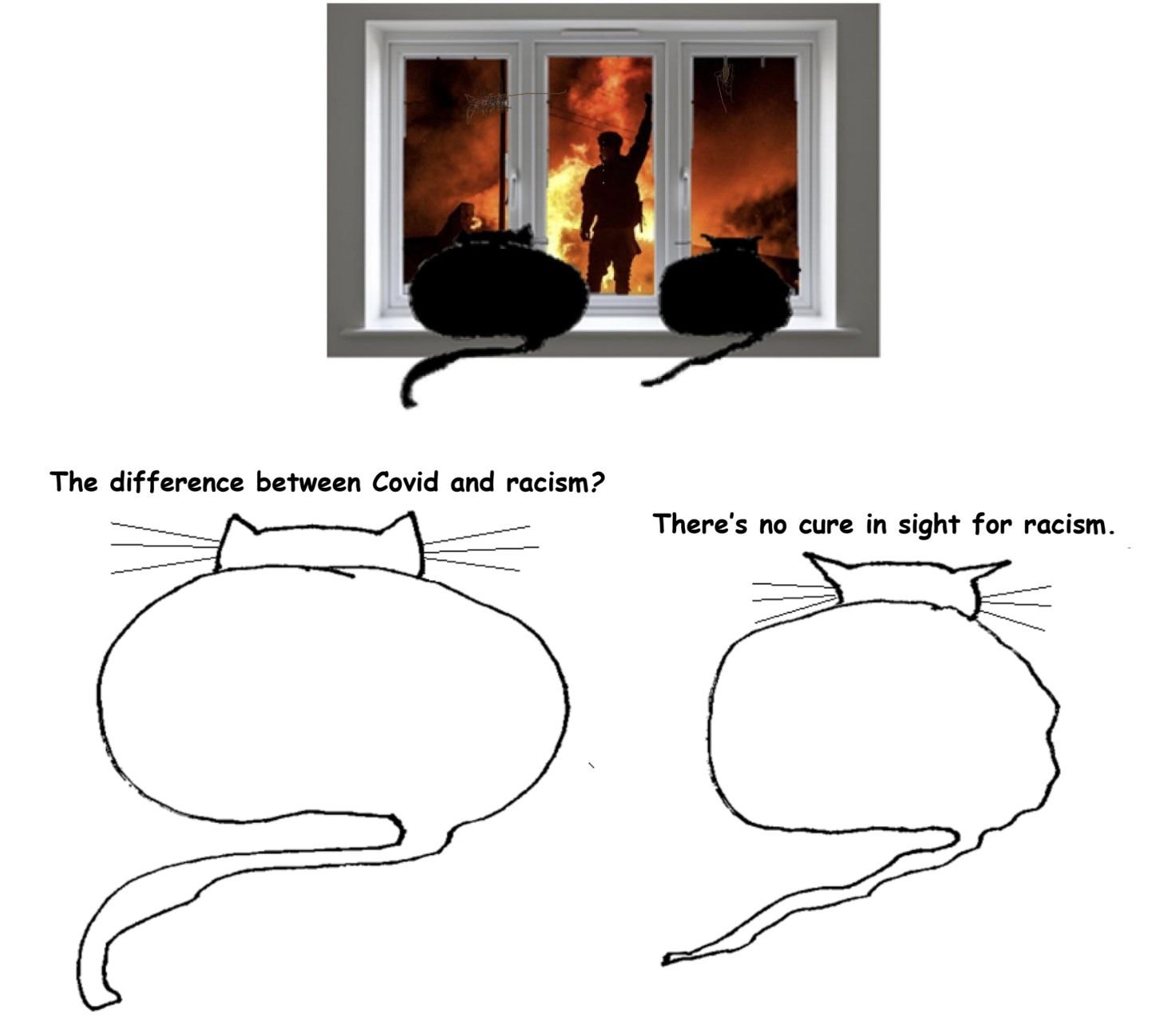

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

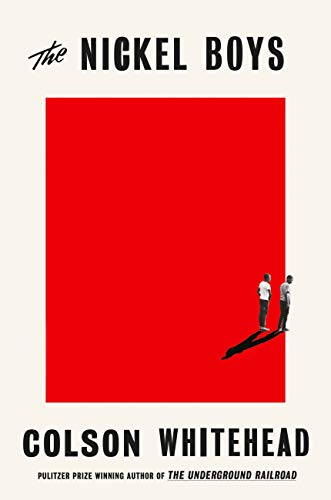

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

It feels impossible this week not to talk about George Floyd, and yet it feels as if talk has become egregiously cheap, less a mechanism for change than a means of resting in paralyses of complacency, disbelief, or comfort. When rage, grief, frustration, and loss take over communities, states, and entire countries as they have this week, words feel at once like our most important tool and a frantic means of filling what could otherwise be a devastating silence. How do we address a racism so deeply ingrained in society that it feels woven into every fiber of our country’s foundation—and, indeed, was there at the United States’ genesis, when black bodies bolstered a white economy at the expense of their lives, health, and humanity, and in the process built what we so misguidedly call the land of the free, the world’s first great democracy?

It feels impossible this week not to talk about George Floyd, and yet it feels as if talk has become egregiously cheap, less a mechanism for change than a means of resting in paralyses of complacency, disbelief, or comfort. When rage, grief, frustration, and loss take over communities, states, and entire countries as they have this week, words feel at once like our most important tool and a frantic means of filling what could otherwise be a devastating silence. How do we address a racism so deeply ingrained in society that it feels woven into every fiber of our country’s foundation—and, indeed, was there at the United States’ genesis, when black bodies bolstered a white economy at the expense of their lives, health, and humanity, and in the process built what we so misguidedly call the land of the free, the world’s first great democracy? My father had an immensely fat friend whom I often glimpsed filling a plate alone at the buffet table of the King Eddie’s restaurant as I walked past that grand hotel. This man himself had a father even then in those days a nonagenarian, whom he saw daily, devotedly, taking him to the pool for a swim. It turned out that, obesity or no obesity, the friend would outlive my own father by twenty years. Because I liked the man very much, his longevity does not strike me as an injustice. He had a snuffling voice, small but piercing eyes, a gigantic nose and a fund of forgiving affection, the kind dispensed even in the awareness that what was being forgiven might have been awful. He preferred not to know, though his ignorance was (if I may venture a paradox) well informed. My mother played matchmaker for decades in his behalf, possibly because she found him appealing. Her stratagems did not avail. His marvellous acquitting heart remained unpaired.

My father had an immensely fat friend whom I often glimpsed filling a plate alone at the buffet table of the King Eddie’s restaurant as I walked past that grand hotel. This man himself had a father even then in those days a nonagenarian, whom he saw daily, devotedly, taking him to the pool for a swim. It turned out that, obesity or no obesity, the friend would outlive my own father by twenty years. Because I liked the man very much, his longevity does not strike me as an injustice. He had a snuffling voice, small but piercing eyes, a gigantic nose and a fund of forgiving affection, the kind dispensed even in the awareness that what was being forgiven might have been awful. He preferred not to know, though his ignorance was (if I may venture a paradox) well informed. My mother played matchmaker for decades in his behalf, possibly because she found him appealing. Her stratagems did not avail. His marvellous acquitting heart remained unpaired.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point.