by N. Gabriel Martin

Perhaps there is no greater testament to the triumph of individualism than the pro-gun slogan “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” It takes an extremely narrow conception of responsibility to deny that lax gun laws are to blame for high rates of gun violence, but that view is pervasive anyway. Now, however, the Black Lives Matter movement is drawing broad popular attention to the fundamentally systemic character of racism, and giving us an opportunity to overthrow individualism.

Individualism stands in the way of serious public debate about many of our most serious social and political problems—from gun control to the erosion of public infrastructure and the racial wealth gap. That’s because it makes the onerous demand that in order to identify a problem, you’ve also got to find out who is responsible. F. A. Hayek, one of the principle architects of this ideology, put it like this: “Since only situations which have been created by human will can be called just or unjust, the particulars of a spontaneous order cannot be just or unjust: if it is not the intended or foreseen result of somebody’s action… this cannot be called just or unjust.”[i]

According to Hayek, complaining about a circumstance for which no one is entirely to blame is like complaining about the weather. It isn’t enough to point to some inequality, such as the gender pay gap, to recognise it as a social problem that we should try to correct. We can identify it as a fact, but in order to see that it is a problem, you have to find a culprit. Otherwise, doing something that alters it would actually be unjust (it might take money away from men, or take autonomy away from corporations).

The result is that we can prosecute the person who pulled the trigger, after they have already killed, but we’re powerless to do anything to stop the next gunman. Read more »

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

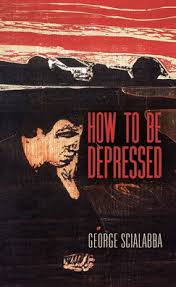

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

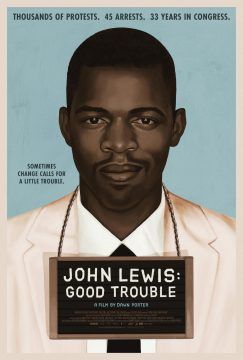

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble