by Joan Harvey

Let’s face it, I’m tired. A phrase completely knotted up in the rather damaged circuitry that is my brain with Madeline Kahn in Blazing Saddles who managed to out-Dietrich Dietrich while being her own amazing self (if you haven’t watched this in at least the past few days you probably should). But, for better or worse, unlike Kahn, my tiredness is not from thousands of lovers coming and going and going and coming and always too soon.

But I digress. Tiredness is a digression from normal life. Repeated rounds of tiredness have been one of the leftovers people have reported experiencing from Covid-19, and, as I looked into it, from other viruses as well. I doubt I had Covid-19, but I did get very ill after flying back from NYC in late January and I’ve been struggling with recovery ever since. The tricky thing, the thing that really sucks, is that whereas with most bouts of tiredness one can recover relatively quickly and start normal physical activity, with this post-viral business, even tiny amounts of exercise can deplete one so much that only days of total rest really help. And, though I have past experience with this, I’m still not particularly well trained for it. The bigger problem, for me as well as others with this type of fatigue, is that one can feel fine during exercise, and then afterward become, as I have been, completely exhausted and shaky for days. As a pamphlet describing post-viral fatigue puts it, “Doing too much on a good day will often lead to an exacerbation of fatigue and any other symptoms the following day. This characteristic delay in symptom exacerbation is known as post-exertional malaise (PEM).” Read more »

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

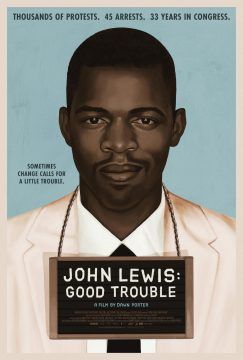

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble