by N. Gabriel Martin

The pandemic has increased our awareness of the moral significance of our day to day habits. While there have always been moral perfectionists who agonise over every choice and action, most of us tended to draw a line under our day to day habits, taking them for granted and reserving moral scrutiny for the extraordinary.

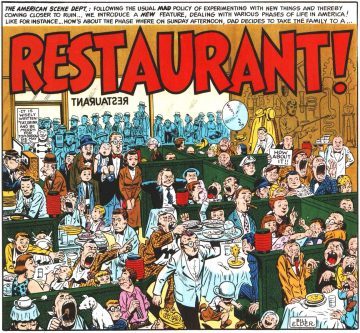

It’s not that eating out, buying chocolate, or going to a party were ever devoid of all moral significance—it was always possible to scrutinise, for example, the labour practices under which chocolate was grown, or the environmental impact of packaging—it just didn’t seem obligatory. Even though we might have known that the choice to buy a chocolate bar had moral significance, we were, for the most part, used to ignoring it. To do otherwise was a lifestyle choice, and not a necessity. That has changed with the coronavirus. Suddenly, we have had to examine—in our own consciences, with our families, and on social media—the choices we used to take for granted.

The pandemic brought moral considerations home to us, into our lives. We can no longer draw a sharp line between obviously immoral actions—spousal betrayal or shoplifting, for example—and the everyday, morally ambiguous ones that we were not used to subjecting to scrutiny. For any one person, visiting a friend, going to a café, or taking a train are not activities that are more likely than not to cause harm to anyone (even now), but if we all carry on with these activities then people will suffer and die and our public health systems will become overwhelmed. As a result, we are now confronted with the moral seriousness of the choices we used to take for granted. Read more »

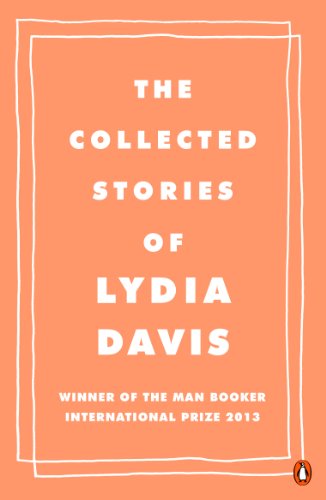

In one sense, the stories of the collection Almost No Memory, originally published in 1997 and reprinted in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis in 2009, can be read as a psychological portrait of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with all the usual things life has to offer after a certain age: the convolutions of domestic discord, shrinking horizons, the sobering insight that very little can change us anymore. The voices are both many and one, converging in a polyphony of percipient anxiety and resignation: we hear “wife one,” an “often raging though now quiet woman” eating dinner alone after talking on the phone to “wife two”; a professor who fantasizes about marrying a cowboy, although she is “so used to the companionship of [her] husband by now that if I were to marry a cowboy I would want to take him with me”; and a woman who “fell in love with a man who had been dead a number of years.” There is also a woman who “comes running out of the house with her face white and her overcoat flapping wildly,” crying “emergency, emergency”; a woman who wishes she had a second chance to learn from her mistakes; and one who has “no choice but to continue to proceed as if I know altogether what I am, though I may also try to guess, from time to time, just what it is that others know that I do not know.” The list continues, from a woman wondering why she can become so vicious with her children to another whose mind wanders to sex at the sight of “anything pounding, anything stroking; anything bolt upright, anything horizontal and gaping” and one who is filled with “ill will toward one I think I should love, ill will toward myself, and discouragement over the work I think I should be doing.”

In one sense, the stories of the collection Almost No Memory, originally published in 1997 and reprinted in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis in 2009, can be read as a psychological portrait of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with all the usual things life has to offer after a certain age: the convolutions of domestic discord, shrinking horizons, the sobering insight that very little can change us anymore. The voices are both many and one, converging in a polyphony of percipient anxiety and resignation: we hear “wife one,” an “often raging though now quiet woman” eating dinner alone after talking on the phone to “wife two”; a professor who fantasizes about marrying a cowboy, although she is “so used to the companionship of [her] husband by now that if I were to marry a cowboy I would want to take him with me”; and a woman who “fell in love with a man who had been dead a number of years.” There is also a woman who “comes running out of the house with her face white and her overcoat flapping wildly,” crying “emergency, emergency”; a woman who wishes she had a second chance to learn from her mistakes; and one who has “no choice but to continue to proceed as if I know altogether what I am, though I may also try to guess, from time to time, just what it is that others know that I do not know.” The list continues, from a woman wondering why she can become so vicious with her children to another whose mind wanders to sex at the sight of “anything pounding, anything stroking; anything bolt upright, anything horizontal and gaping” and one who is filled with “ill will toward one I think I should love, ill will toward myself, and discouragement over the work I think I should be doing.” Undoubtedly many insights and lessons can be drawn and will be drawn for a long time to come from the current worldwide covid19 epidemic; insights, for example, about the responsibility of politicians in the managing of health crises, about the importance of human cooperation both locally and internationally, about the vulnerability of the global economy to disturbances in the regular flow of people and commodities, about the crucial yet contentious role of the various media in the dissemination of information, etc. But here I am interested in focusing briefly on related issues regarding the problematic relationship of science and the general public. Specifically, I want to offer some reflections on why I think science in trying times can be hard to live with.

Undoubtedly many insights and lessons can be drawn and will be drawn for a long time to come from the current worldwide covid19 epidemic; insights, for example, about the responsibility of politicians in the managing of health crises, about the importance of human cooperation both locally and internationally, about the vulnerability of the global economy to disturbances in the regular flow of people and commodities, about the crucial yet contentious role of the various media in the dissemination of information, etc. But here I am interested in focusing briefly on related issues regarding the problematic relationship of science and the general public. Specifically, I want to offer some reflections on why I think science in trying times can be hard to live with.

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’ I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson.

I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson. We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.

We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.  America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.