by Pranab Bardhan

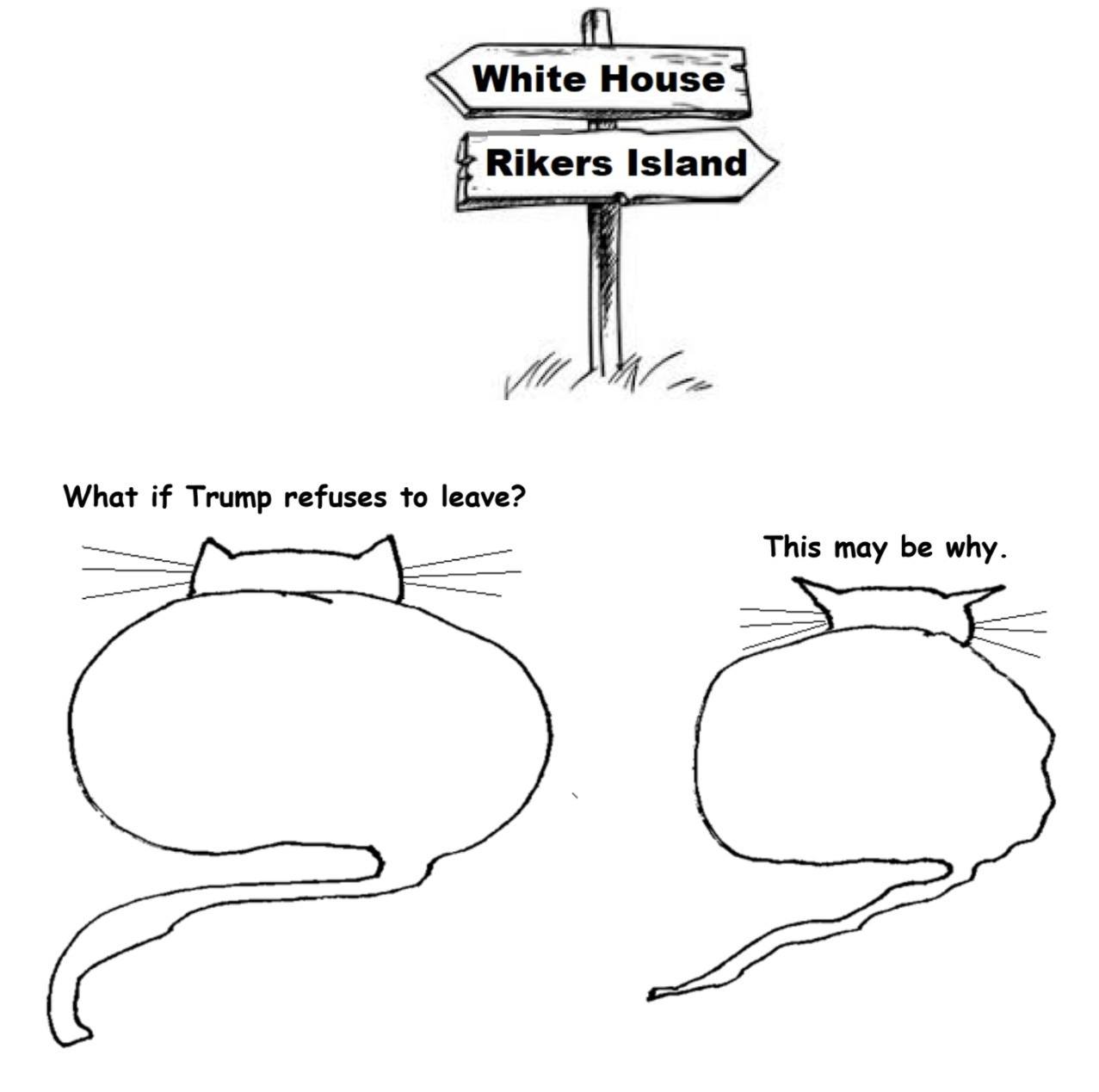

In my earlier column, “Prospects of Social Democracy in a Post-Pandemic World” I did not have the time or space to discuss some systemic issues, like the fraught link of social democracy to the capitalist mode of production. Different people mean different things when they talk of social democracy and its somewhat close kin, democratic socialism. I usually associate the former with the mode of production remaining essentially capitalist, though with some important modifications, and the latter with the case where the ownership or control of the means of production is primarily with non-private entities (the state or cooperatives or worker-managed enterprises). In this sense Bernie Sanders and his followers wrongly describe themselves as democratic socialists, to me they are social democrats.

In my earlier column, “Prospects of Social Democracy in a Post-Pandemic World” I did not have the time or space to discuss some systemic issues, like the fraught link of social democracy to the capitalist mode of production. Different people mean different things when they talk of social democracy and its somewhat close kin, democratic socialism. I usually associate the former with the mode of production remaining essentially capitalist, though with some important modifications, and the latter with the case where the ownership or control of the means of production is primarily with non-private entities (the state or cooperatives or worker-managed enterprises). In this sense Bernie Sanders and his followers wrongly describe themselves as democratic socialists, to me they are social democrats.

In social democracy those important modifications to the capitalist mode of production may involve some substantial reform in the governance of the firm and in the fiscal power of the democratic state to raise taxes to fund a significant expansion of redistributive and infrastructure programs. Yet these modifications will remain constrained by what used to be called the ‘structural dependence’ on private capital. How far that structural limit can be pushed will vary with a country’s institutional history, political culture, and social norms. Much will depend on how far the modifications of capitalism can leave unhampered the mechanism of productivity growth and innovation, which Schumpeter considered the engine of capitalist dynamics. Is there a magic balance achievable under social democracy? This will be central to my discussion in this article, as I often find that my social-democratic and democratic-socialist friends do not pay adequate attention to the question of innovations. I shall also comment on the need for significant reforms in the financial system, labor market policy and election funding for a social democracy to function properly, Read more »

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

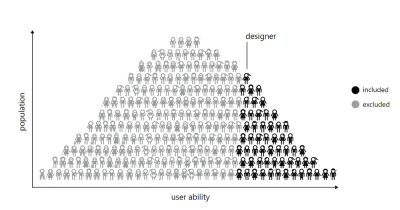

by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir. I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie

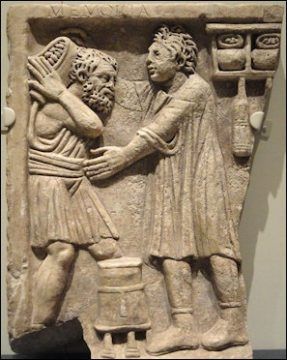

I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie  Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.