by N. Gabriel Martin

When I was younger, I gravitated to conservatism’s deference to the actual. In my suspicion towards the progressive preference for ideas over what just is, it took me a long time to understand that conservatism misunderstands the future and therefore what it is attempting to achieve. Conservatism’s purported ambition to preserve the present and its roots in tradition are also efforts to bring about a different future, and therefore to change the world to suit its designs. However, it took me a long time to understand this self-contradiction at its heart.

In college I had a running argument with my friend Sky about Damien Hirst, the artist most famous at the time for suspending a great white shark in a tank of formaldehyde. Hirst was never my favourite artist (I actually like him more now than I did then), but I defended him because Sky’s dismissal appalled me. In my youth I embraced the culture as if it were a stately home I’d been welcomed into. While I was not uncritical, for me criticism had to come from a well of reverence for what was already there. It was the sanctity of established culture, tradition, and history that made criticising it worthwhile, and so criticism could never undermine that sacredness. Sky, however, criticised Hirst because she preferred a culture without him and what he was doing to it. I never understood that in my twenties, because I couldn’t understand the future.

At that time, the only way to respond to the world that made sense to me was to accept it and affirm it as it was, and comment on it as a passionate, but disinterested, observer. It wasn’t just that I revered tradition, I was also sceptical towards what I saw as the arrogance of progressivism; that it wants to improve upon things and believes it can. Read more »

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s

Michele Morano’s first collection of essays, Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, is a classic of travel literature that I have taught several times, to the great pleasure of over a decade’s worth of students. Now she has bested the power of that excellent book with a new collection of essays,

Michele Morano’s first collection of essays, Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, is a classic of travel literature that I have taught several times, to the great pleasure of over a decade’s worth of students. Now she has bested the power of that excellent book with a new collection of essays,

If you go to Kashmir today this is what you will see. As you drive away from Srinagar’s Hum Hama airport, a large green billboard with white lettering proclaims, Welcome to Paradise.

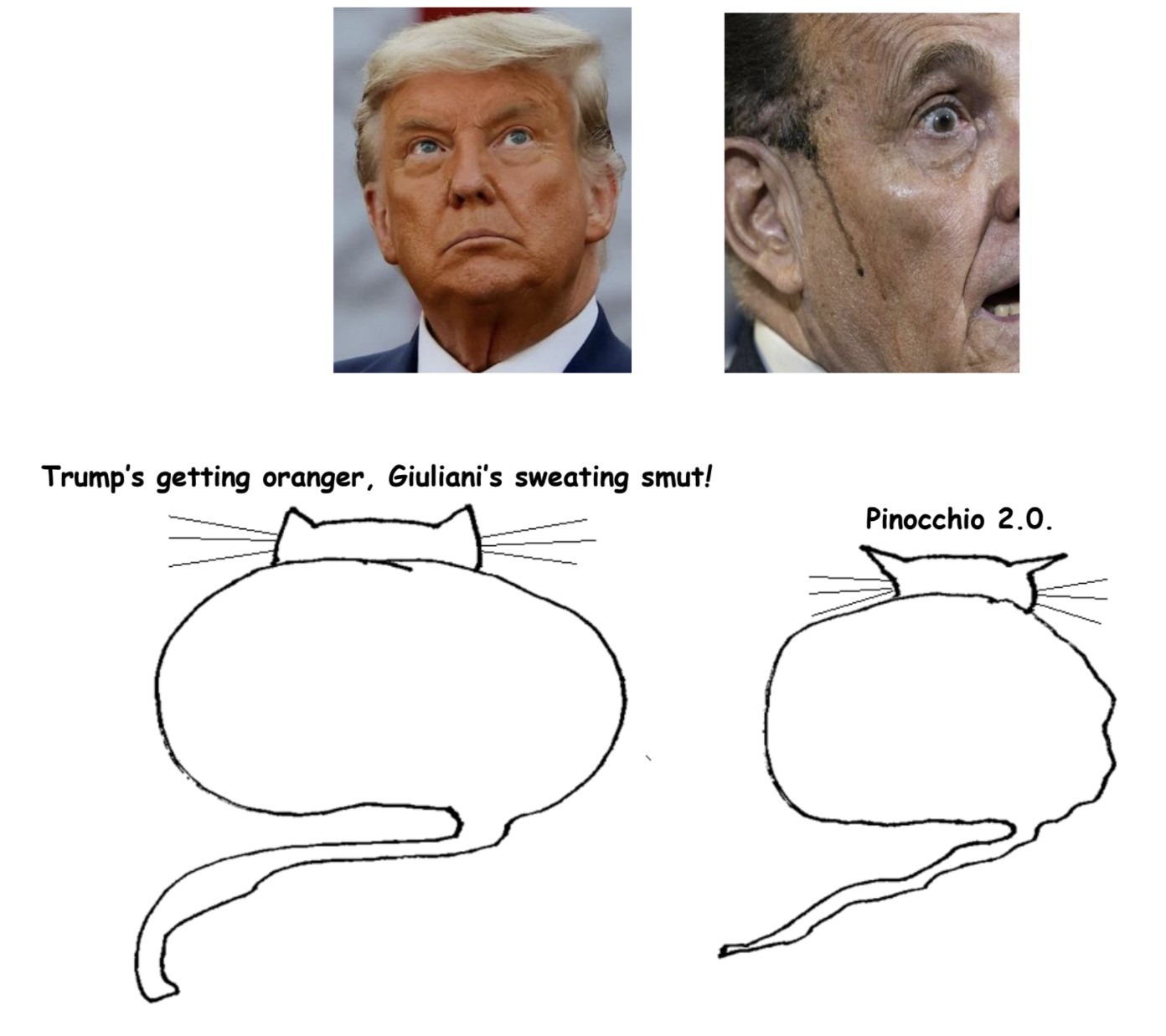

If you go to Kashmir today this is what you will see. As you drive away from Srinagar’s Hum Hama airport, a large green billboard with white lettering proclaims, Welcome to Paradise. Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election.

Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election. The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has

The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has