by Carol A Westbrook

Men have always wanted to fly to the moon and stars. We wanted to find out what was up there on the moon and planets? Was it heaven? Were there angels? Or were these worlds inhabited by strange creatures who built canals? We looked up, we used telescopes. We watched the stars and charted their movements. But we wanted to do more than look and imagine; we wanted to go up there and see for ourselves? The birds could fly, why couldn’t we?

Men have always wanted to fly to the moon and stars. We wanted to find out what was up there on the moon and planets? Was it heaven? Were there angels? Or were these worlds inhabited by strange creatures who built canals? We looked up, we used telescopes. We watched the stars and charted their movements. But we wanted to do more than look and imagine; we wanted to go up there and see for ourselves? The birds could fly, why couldn’t we?

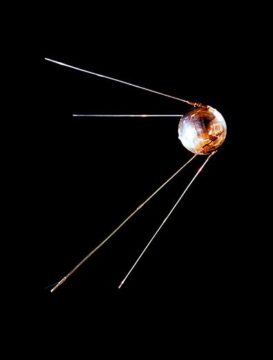

But man remained earthbound until that historic day in 1903, when the Wright brothers left the ground at Kitty Hawk in the first manned, self-propelled flight. The age of flight began. Barely fifty years later, Sputnik was launched into space. Ten years later man walked on the moon. We watched the moonwalk with great excitement and anticipations. We knew it was now just a matter of time before we ourselves would get our own chance to do the same—to experience weightlessness of space, to see the moon up close, to walk on the surface of the moon.

So we waited. And waited. We dreamed about space travel, wrote books and made movies about it. “Fly Me to the Moon,” Frank Sinatra sang for us. (Click here for the song.) We grew old, and we still waited. The longer we waited, the further our dreams seem to get. Initially there were plans for more flights to the moon and perhaps a settlement, followed by exploration of Mars. Instead, NASA launched the International Space Station, or ISS.Travel to the ISS was to be by the space shuttle. Maybe we could hitch a ride and go along, too? But after the tragic crash of the Space Shuttle in 1986, in which everyone aboard perished, including the first civilian passenger, Sharon McAuliffe, NASA said, “no more civilians in space.” The shuttle project was cancelled. Read more »

My Presidency College friend Premen was always a voracious reader, particularly of political, social and military history. He often told me of new books in those areas and sometimes persuaded me to read them. But by the time I saw him again in Cambridge, I could see his slow turn from his fascination with Trotsky to Mao. This was in line with a general movement among the young in the European left around that time. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise captured the restless energy of politically-activist students in contemporary France, foreshadowing the student rebellions in a year or so.

My Presidency College friend Premen was always a voracious reader, particularly of political, social and military history. He often told me of new books in those areas and sometimes persuaded me to read them. But by the time I saw him again in Cambridge, I could see his slow turn from his fascination with Trotsky to Mao. This was in line with a general movement among the young in the European left around that time. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise captured the restless energy of politically-activist students in contemporary France, foreshadowing the student rebellions in a year or so. Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible. Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

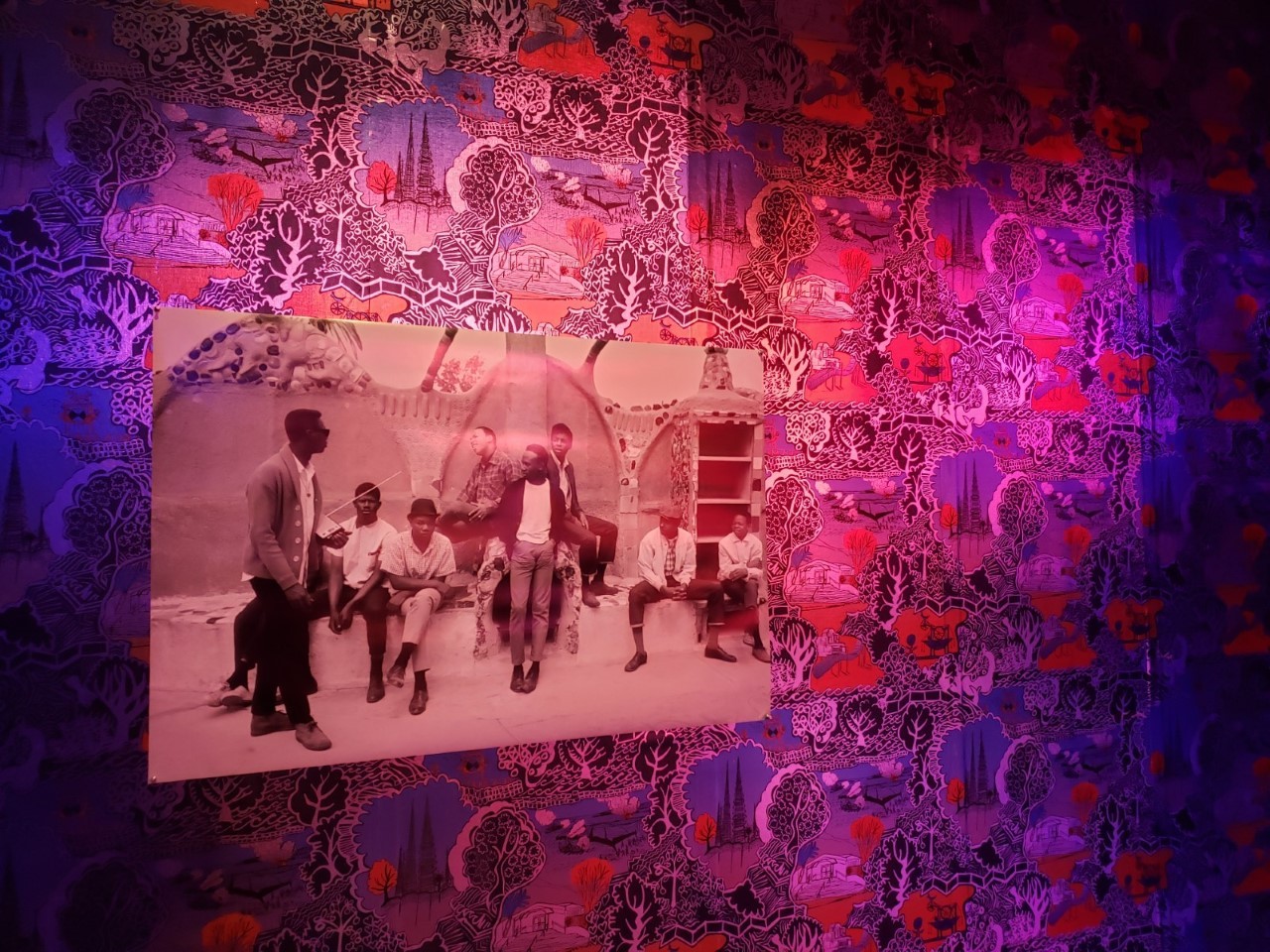

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018.

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018.