by David J. Lobina

So yet another controversial topic from me, and thus another go at getting cancelled. A long series of pieces on the use and abuse of the term fascism by American commentators (here, here, and here), a dismissal of a dismal “academic” book on inclusion in linguistics (here), and an argument that universality trumps diversity in most respects (here) haven’t done the job, so perhaps a put-down of the current fad on all things equity will finally get me walking.

But isn’t equity an economic thing, a concern of business people, with little to do with equality per se? If anything, equity-qua-stocks would be related to inequality… That was the very reaction of a friend of mine, Italian and philosopher as he happens to be, when I told him I was writing about equality and equity. And no surprises there, for equity is not a common concept in political philosophy, where equality has been most discussed. In fact, the focus on equity is mostly a North American phenomenon, first originating within social justice movements and now very present in business circles too. And such is the soft power of the US (and this is stuff coming from the US) that this sort of social and political discourse can easily travel beyond those shores. But for my money it is really the fault of LinkedIn, that cesspool of naked self-promotion and half-baked ideas and advice.

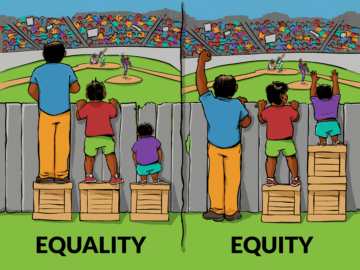

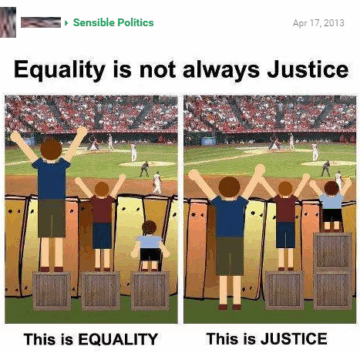

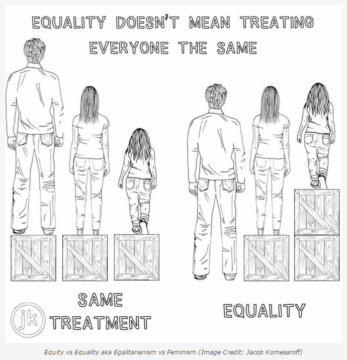

Interestingly, the original version of the meme heading this post made a different point:

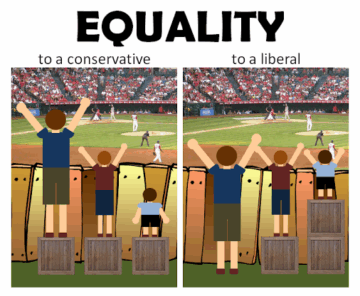

As the original graphic shows (see endnote 1 for more details), the aim was to differentiate between two different ideas of equality, at least from the perspective of what the terms conservative and liberal are taken to mean in North American political discourse (which, as I discussed here, doesn’t necessarily apply elsewhere, certainly not piecemeal). The intent behind the original graphic was not to contrast equality and equity, let alone was it a defence of equity over equality – the very opposite of what I shall argue for here, then.

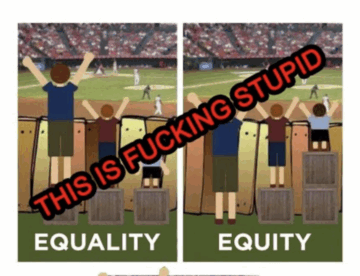

So what is problem with the (modified) equity-over-equality meme? In short, and to put it in bullet-point form for the LinkedIn crowd before fleshing out some of the details:

- the meme is based on a misleading and infantile understanding of what equality actually involves, contra decades of work in political philosophy and elsewhere;

- it treats the notion of equity as an independent concept from equality, even though the former seemingly subsumes the latter, and does so in an equally childish manner to how equality is treated, all based on definitional fiats and no argument; and,

- in the end the meme is often co-opted to defend the idea that different tiers in companies or political bodies ought to be composed of members of minority groups in proportion to their share of the population, and this ends up becoming an elitist concern, thus leaving most societal inequalities untouched.

But to go back to the original meme first for a minute: two different ideas regarding equality are presented therein, one focused on equality of opportunities (or, more accurately, on equality of recourse allocation), and one focused on equality of outcomes, with only one of these two supposedly incompatible views endorsed – namely, the “liberal” view that equality of outcomes should be generally favoured. A little bit on the nose, and certainly far too simplistic, but at least the original stays with the concept of equality tout court.

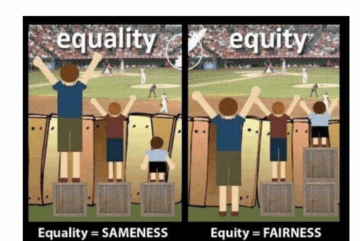

The modified meme, on the other hand, presents equality as a concept that stands for treating everyone in exactly the same way (as in equal treatment, with no nuance of any kind allowed), with equity standing for not treating everyone in exactly the same way, but in terms of their needs towards achieving a goal (an outcome).

So framed, it is no surprise that posts such as this joke that if you want to make a philosopher angry you should show them the “equity meme”. Why the reaction, though?

Firstly, the impetus behind the general idea of equal treatment is in respect to a particular desideratum; in the most usual case, the expectation is for people to be treated equally in respect to the law – that is, for everyone to receive equal rights and not be discriminated against. This is uncontroversial and the opposite would be outrageous and unacceptable; the principle is enshrined in Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (with emphasis on universal), among other places, and it is meant to apply regardless of anyone’s circumstances or characteristics. There is nothing wrong about equal treatment per se.

Secondly, in political philosophy the concept of equality implies similarity, not sameness (the latter would be the relation of identity); that is, equality is the idea that people are all alike in important and relevant respects – what’s sometimes called the “egalitarian plateau” of all theories of equality – but this does not mean that everyone is the same in all respects or that people ought to be treated in exactly the same way. Indeed, even though the idea of a moral equality is universally accepted – scholars and most lay people will agree that all human beings are equal in worth and moral status – the proposition that people should be treated equally in all respects is not really a position that is defended by anyone.[iii]

In addition, equality is a much richer concept than the meme allows for, and it is most definitely not reducible to the notion of “equal treatment” in any way. There is indeed a lot more to say about how equality is discussed in political philosophy, and from different perspectives to boot: from issues around social equality (equal rights, liberties, status, etc.) and substantive equality (namely, equality of outcomes), both traceable to Ancient Greece discussions, to more modern analyses of equality in terms of equal opportunities, the question of “what” to equalise (is it income? wealth? resources?), how to accommodate the need to neutralise the effects of bad choices and also bad luck (think of the height differentials in the silly meme), and much else.

Thirdly, and somewhat following up from the previous point, it is noteworthy that most descriptions of equity employ the language of equality through and through – that is, it is not a simple matter to define equity without using the term “equality” in the definition. As a case in point, this paper is somewhat at pains to disentangle the concepts of equity and equality, at one point providing five different connotations of equity that are all in fact different versions of equality. And yet the conclusion the equity meme wants us to draw is that equality is not the objective to pursue, even though equity is being assumed to mean “equality of outcomes” to begin with – isn’t equity a particular instance of equality, then?

If nothing else, the meme makes a confused point as a result of employing a convoluted (and mistaken) way to describe equality and equity. The equity meme is also not a little retrograde, as it basically does away with more than 50 years of the study of equality in one single stroke, even if it eventually dismisses an understanding of equality that no-one actually holds (this afore-linked post makes a similar point). It is not quite a case of setting up a straw-man, but the meme does draw a false dichotomy between equality and equity.[iv]

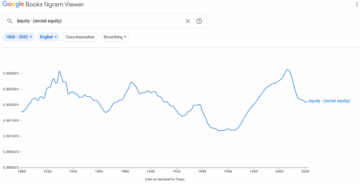

I also think the definition of equity in the meme is mostly made up (it is not a common concept in political philosophy), somewhat of recent invention (as we shall see), and most certainly unnecessary (as we shall also see!), a general point that receives some support from how the words “equality” and “equity” have been used in the past, both in lay terms and in the specialised literature.

The word “equality” is first attested in English in the 14th century, was adapted partly from French, and partly from Latin, and its frequency of usage increased from the 1900s onwards. Apart from the connotations of quantities or expressions being the same (in mathematics) and of having the same degree or quality of power, status, etc., the most relevant meaning here is that of the condition of everyone having the same rights, advantages or opportunities, especially regardless of differences in sex, ethnicity or class (this is entry 5.b in the Oxford English Dictionary, the OED). The word “equity”, on the other hand, comes from French, is first attested in the 14th century, and its frequency of usage increased from the 1960s onwards. The most relevant connotation for us is that of being equal or fair (the language of equality again; this is entry I.1 in the OED), though the most common usage must come from either the law (as a part of the system of law in both the UK and the US) or the realm of economic activities (equity as shares or stock).

More relevant to our purposes, the 1960s saw the first appearance of the concept social equity in the context of race relations in the US as it pertains to the justice and fairness of social policies, especially policies that are based on “substantive equality” (as mentioned, the latter means equality of outcomes).[v] And as it happens, it is the particular construct of “social equity” that underlies the equity meme and orbiting discussions. But to labour the point once more: if social equity is based on a specific version of equality – substantive equality – and this was an already well-established concept, why multiply terms?

But my qualms about the equity meme are not really focused on the mistreatment of the concept equality or the invented characterisation of equity, but what the meme is often co-opted to do and defend – so, not really about the first two bullet points, but the third.

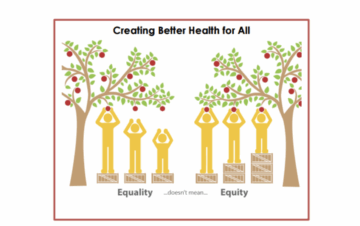

Let’s consider what may well be regarded as one of the central questions regarding equality of outcomes in order to approach the issue I have in mind, and let’s do so by considering economic inequality first – namely, the question of what requirement constitutes the target to bring equality of outcomes about. I will then move to the health and educational sectors, as these sectors have both been particularly susceptible to the equity talk in recent times.

Starting from the premise that equality of outcomes in the economic context would be a state in which everyone has approximately the same material wealth and income, such a target would necessitate accounting for who exactly is in a position of economic inequality and then setting up a way to transfer income and wealth so that these are more widely spread in a population. As such, economic inequality may well involve some kind of affirmative action or quota system in order to cater for the individual needs of those with little income or wealth.

In the case of the health and education sectors, the outcomes are straightforward: a person’s full potential for health and well-being, as per the World Health Organization (here), and equal learning opportunities for everyone, as per the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (here). And these in turn are based on basic, underlying properties of human nature – namely, specific expectations as to how an organism develops and functions with medical support (as understood in biology), and specific expectations that all students ought to ‘achieve similar levels of performance in key cognitive domains, such as reading, mathematics and science, and similar levels of social and emotional well-being’ (as understood in cognitive psychology; quote is from here).

This does not mean that everyone is expected to achieve the same health and educational outcomes, though it is certainly assumed that everyone ought to achieve minimum standards in each case, everything else being equal. This is clearest in the educational sector, which uncontroversially adopts national curricula and the like, and where the expectation is that everyone ought to be able to achieve the same common standards – a universal assumption if there ever was one, and one based on the idea that everyone is equally capable of achieving the same standards. So, again, all about equality, isn’t it?

Not so, the equity meme people might say; the issue, they would say, is that we cannot simply provide every individual with the very same resources and expect them to achieve the relevant standard – that’s equality, you see, though everyone should certainly have access to the same resources (no contradiction here?). What we need to do instead, the equity people claim, is allocate resources on an individual need-based manner. But how is that different from what educational and health systems have always done, anyway? No-one is treated exactly the same in a school or at the doctor’s, after all; indeed, teachers and doctors are very well aware that catering for individual needs is part and parcel of their job. In this sense alone, what the focus on equity seems to yield is just a platitude.

In another sense, the focus on such an understanding of equity is misguided. The strongest predictor for good health and educational outcomes is socioeconomic status, a bundle of features (income, race, class, etc.) that do not correlate all that well with each other, and a concept that is best measured as the income-to-needs ratio. And thus the main problem here is economic inequality, not inequity as currently understood.

As a matter of fact, the focus on equity in the US has resulted in a situation where it is mostly an elitist concern; indeed, equity measures such as affirmative-action policies for the most part have aimed at achieving representation of minority groups in positions of power and responsibilities, be these in company boards or politics, in accordance to their share of their population, but what this yields is a more ethnically diverse elite, not a more equal or fairer society. The preference for micro-interventions here and there with such narrow aims instead of universal social programs to reduce inequality ends up leaving inequality mostly intact, with grave repercussions for most of the population. The educational sector in the US is a case in point, given that American schools are largely funded by local property taxes within the corresponding school district, and it is this factor that will determine one’s outcomes much more robustly than affirmative actions and the like. You can have plenty of representation in top positions (be these in politics, finance or even sports and entertainment), but if you live in a very unequal society and you are brought up in a rather deprived area, your future prospects are significantly curtailed. To put it bluntly, you can have all the equity you want, but without a more equal society, at every level, class segregation will be widespread and most people will remain immiserated in the long run.

—

But to come back to why the equity meme annoys philosophers: this is mostly because those who bring it up are convinced they are making a profound point, and this is not the case at all. The equity meme is confusing and confused, and in the event its main point is a platitude. Just say you are catering for people’s individual needs if that’s what you mean, or that you support affirmative action for minorities in elite positions. But just kill the silly meme and stop pontificating.

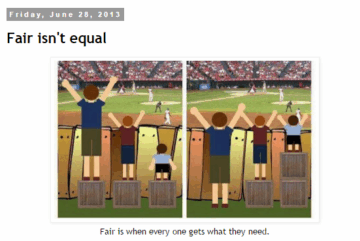

[i] Here starts the shameful history of a silly meme, with little commentary but presenting some of the different iterations in chronologically order (see here for a running commentary of these and other iterations of the meme from the original maker of the graphic, who shall remain nameless):

The original image, about two versions of equality (supposedly).

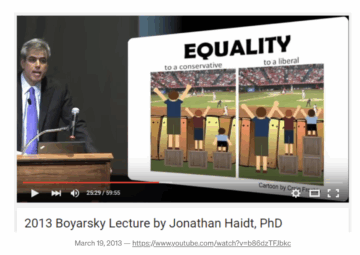

Jonathan Haidt was the first to give it some airtime, befitting both his style and intellectual nous.

Someone quite confused reduces equality to equal treatment in all respects and contrasts it to justice.

Someone is even more confused.

Someone else just makes stuff up and ignores the past.

Everyone can make stuff up.

Finally someone with some sense!

Even more sense!

[ii] I once started a short piece on neuromorphic computing for a technology consultancy with the very same initial phrasing in this post, and I was quite disappointed that no-one during the editing process called me out on my choice of words. Oh, I’m of course joking about your favourite social network – I mean LinkedIn, which is the worst social network around, and that’s saying something with Twitter still around (there’s something about naked capitalists pontificating about that is even more offensive than naked racists prancing around).

[iii] The Equality entry from the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy is most useful here, and wherefrom I’m drawing in these few paragraphs. On similarity and sameness, though, see this piece of mine on how everyone is indeed the same when it comes to basic cognitive processes.

[iv] The author of this piece, someone who was to be a US Supreme Court judge, should really have known better, and have written a better article about equality and equity.

[v] I have mentioned that the frequency of usage of the word “equity” increased from the 1960s on, but this is unlikely to be due to the appearance of “social equity” as a new concept, at least according to Google Books Ngram Viewer (equity-as-stock is probably the most common meaning):

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.