Harry T Dyer in LiveScience:

Speakers recently flew in from around (or perhaps, across?) the earth for a three-day event held in Birmingham: the UK’s first ever public Flat Earth Convention. It was well attended, and wasn’t just three days of speeches and YouTube clips (though, granted, there was a lot of this). There was also a lot of team-building, networking, debating, workshops – and scientific experiments. Yes, flat earthers do seem to place a lot of emphasis and priority on scientific methods and, in particular, on observable facts. The weekend in no small part revolved around discussing and debating science, with lots of time spent running, planning, and reporting on the latest set of flat earth experiments and models. Indeed, as one presenter noted early on, flat earthers try to “look for multiple, verifiable evidence” and advised attendees to “always do your own research and accept you might be wrong”.

Speakers recently flew in from around (or perhaps, across?) the earth for a three-day event held in Birmingham: the UK’s first ever public Flat Earth Convention. It was well attended, and wasn’t just three days of speeches and YouTube clips (though, granted, there was a lot of this). There was also a lot of team-building, networking, debating, workshops – and scientific experiments. Yes, flat earthers do seem to place a lot of emphasis and priority on scientific methods and, in particular, on observable facts. The weekend in no small part revolved around discussing and debating science, with lots of time spent running, planning, and reporting on the latest set of flat earth experiments and models. Indeed, as one presenter noted early on, flat earthers try to “look for multiple, verifiable evidence” and advised attendees to “always do your own research and accept you might be wrong”.

While flat earthers seem to trust and support scientific methods, what they don’t trust is scientists, and the established relationships between “power” and “knowledge”. This relationship between power and knowledge has long been theorised by sociologists. By exploring this relationship, we can begin to understand why there is a swelling resurgence of flat earthers.

Let me begin by stating quickly that I’m not really interested in discussing if the earth if flat or not (for the record, I’m happily a “globe earther”) – and I’m not seeking to mock or denigrate this community. What’s important here is not necessarily whether they believe the earth is flat or not, but instead what their resurgence and public conventions tell us about science and knowledge in the 21st century. Multiple competing models were suggested throughout the weekend, including “classic” flat earth, domes, ice walls, diamonds, puddles with multiple worlds inside, and even the earth as the inside of a giant cosmic egg. The level of discussion however often did not revolve around the models on offer, but on broader issues of attitudes towards existing structures of knowledge, and the institutions that supported and presented these models.

More here.

Michael J. Barany in the LA Review of Books:

Michael J. Barany in the LA Review of Books: Dennis Overbye in the NYT:

Dennis Overbye in the NYT: Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

Corey Robin in The New Yorker: David A. Bell in Dissent:

David A. Bell in Dissent: Empires are strange creatures. Obsessed with their own end-time, they enlist the help of the katechon—a form of political sovereignty that “delays or maintains the end of time”—to postpone the inevitable, and stretch out time before the end. The obsessive fear of decline and an active engagement with trying to delay the end of empire is something that links contemporary right-wing movements to Himmler’s, Spengler’s, and Friedrich Ratzel’s temporal understandings of the basis for the National Socialist empire. The difference between then and now is that Hitler’s “solution” to the racial diversity he diagnosed as one of the core problems contributing to the cyclicity of empires and their inevitable decline was the murder of those the National Socialist regime deemed to be barbarians.

Empires are strange creatures. Obsessed with their own end-time, they enlist the help of the katechon—a form of political sovereignty that “delays or maintains the end of time”—to postpone the inevitable, and stretch out time before the end. The obsessive fear of decline and an active engagement with trying to delay the end of empire is something that links contemporary right-wing movements to Himmler’s, Spengler’s, and Friedrich Ratzel’s temporal understandings of the basis for the National Socialist empire. The difference between then and now is that Hitler’s “solution” to the racial diversity he diagnosed as one of the core problems contributing to the cyclicity of empires and their inevitable decline was the murder of those the National Socialist regime deemed to be barbarians. SAUL STEINBERG CALLED HIMSELF “a writer who draws.” Harold Rosenberg called him “a writer in pictures.” Critics compared him to Klee and Picasso, but reviews were just as likely to namedrop Joyce and Stendhal. He was friends with Nabokov as well as Saul Bellow, Primo Levi, William Gaddis, Donald Barthelme, John Hollander, Charles Simic, and Ian Frazier. Ulysseswas his favorite novel. Nabokov’s essay on Gogol was his guidebook.

SAUL STEINBERG CALLED HIMSELF “a writer who draws.” Harold Rosenberg called him “a writer in pictures.” Critics compared him to Klee and Picasso, but reviews were just as likely to namedrop Joyce and Stendhal. He was friends with Nabokov as well as Saul Bellow, Primo Levi, William Gaddis, Donald Barthelme, John Hollander, Charles Simic, and Ian Frazier. Ulysseswas his favorite novel. Nabokov’s essay on Gogol was his guidebook. S

S THE SIMULTANEOUS RELEASE

THE SIMULTANEOUS RELEASE At the centre of Natalie Haynes’s absorbing, fiercely feminist new novel A Thousand Ships, about the women caught up in the Trojan war, is Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Here, the goddess invoked at the start of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey has something to say about the story that is being told under her guidance:

At the centre of Natalie Haynes’s absorbing, fiercely feminist new novel A Thousand Ships, about the women caught up in the Trojan war, is Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Here, the goddess invoked at the start of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey has something to say about the story that is being told under her guidance: Stepping inside the Notre Dame is a bit like stepping outside of ordinary time and space. The immense verticality of the entire structure, illuminated from outside through light refracted in the colors of the stained glass, isn’t accidental in its immediate effects on our consciousness. We are meant to experience our own smallness relative to its vastness; we are meant to be drawn upwards towards the light pouring in from all sides, and to recognize it as symbolic of an external revelation that illuminates and transfigures our minds and hearts. Her rose windows are meant to be occasions to contemplate the mysteries of human life—birth, love, sex, death—and the nature of eternity. As we enter, we are meant to feel deep in our hearts a yearning for that which is greater than ourselves; if we do not experience this awe and wonder, or stop to contemplate the depths of these mysteries, we have missed something of the structure’s essential intent.

Stepping inside the Notre Dame is a bit like stepping outside of ordinary time and space. The immense verticality of the entire structure, illuminated from outside through light refracted in the colors of the stained glass, isn’t accidental in its immediate effects on our consciousness. We are meant to experience our own smallness relative to its vastness; we are meant to be drawn upwards towards the light pouring in from all sides, and to recognize it as symbolic of an external revelation that illuminates and transfigures our minds and hearts. Her rose windows are meant to be occasions to contemplate the mysteries of human life—birth, love, sex, death—and the nature of eternity. As we enter, we are meant to feel deep in our hearts a yearning for that which is greater than ourselves; if we do not experience this awe and wonder, or stop to contemplate the depths of these mysteries, we have missed something of the structure’s essential intent.

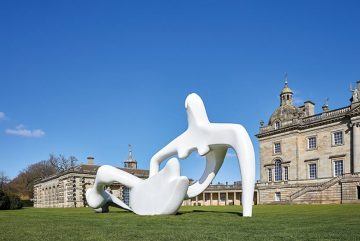

It seemed that Moore needed to start with natural forms, but then move away from them. You don’t really need to know that ‘Arch’ or ‘Three Piece Sculpture’ were inspired by bones in order to enjoy them. What’s important is that, as he said, the sculpture has ‘a force, a strength, a life, a vitality from inside’. And these really do.

It seemed that Moore needed to start with natural forms, but then move away from them. You don’t really need to know that ‘Arch’ or ‘Three Piece Sculpture’ were inspired by bones in order to enjoy them. What’s important is that, as he said, the sculpture has ‘a force, a strength, a life, a vitality from inside’. And these really do. You can find the news about Pakistan’s war on women buried deep inside the metro pages of Urdu newspapers. I stumbled upon it a few years ago. I noticed that I could pick up my newspaper and almost every day find news about a murdered woman. I thought maybe it’s a coincidence, maybe Karachi is a huge city, these things happen. But it went on and on. It became so routine that I could pick up the paper, open the exact same pages, just like you can bet that you’ll find a crossword or letters to the editor, and it was always there.

You can find the news about Pakistan’s war on women buried deep inside the metro pages of Urdu newspapers. I stumbled upon it a few years ago. I noticed that I could pick up my newspaper and almost every day find news about a murdered woman. I thought maybe it’s a coincidence, maybe Karachi is a huge city, these things happen. But it went on and on. It became so routine that I could pick up the paper, open the exact same pages, just like you can bet that you’ll find a crossword or letters to the editor, and it was always there. Ice remembers forest fires and rising seas. Ice remembers the chemical composition of the air around the start of the last Ice Age, 110,000 years ago. It remembers how many days of sunshine fell upon it in a summer 50,000 years ago. It remembers the temperature in the clouds at a moment of snowfall early in the

Ice remembers forest fires and rising seas. Ice remembers the chemical composition of the air around the start of the last Ice Age, 110,000 years ago. It remembers how many days of sunshine fell upon it in a summer 50,000 years ago. It remembers the temperature in the clouds at a moment of snowfall early in the  Nusrat Jahan Rafi

Nusrat Jahan Rafi