George Musser in Nautilus:

It’s not just in politics where otherwise smart people consistently talk past one another. People debating whether humans have free will also have this tendency. Neuroscientist and free-will skeptic Sam Harris has dueled philosopher and free-will defender Daniel Dennett for years and once invited him onto his podcast with the express purpose of finally having a meeting of minds. Whoosh! They flew right past each other yet again. Christian List, a philosopher at the London School of Economics who specializes in how humans make decisions, has a new book, Why Free Will Is Real, that tries to bridge the gap. List is one of a youngish generation of thinkers, such as cosmologist Sean Carroll and philosopher Jenann Ismael, who dissolve the old dichotomies on free will and think that a nuanced reading of physics poses no contradiction for it.

It’s not just in politics where otherwise smart people consistently talk past one another. People debating whether humans have free will also have this tendency. Neuroscientist and free-will skeptic Sam Harris has dueled philosopher and free-will defender Daniel Dennett for years and once invited him onto his podcast with the express purpose of finally having a meeting of minds. Whoosh! They flew right past each other yet again. Christian List, a philosopher at the London School of Economics who specializes in how humans make decisions, has a new book, Why Free Will Is Real, that tries to bridge the gap. List is one of a youngish generation of thinkers, such as cosmologist Sean Carroll and philosopher Jenann Ismael, who dissolve the old dichotomies on free will and think that a nuanced reading of physics poses no contradiction for it.

List accepts the skeptics’ definition of free will as a genuine openness to our decisions, and he agrees this seems to be at odds with the clockwork universe of fundamental physics and neurobiology. But he argues that fundamental physics and neurobiology are only part of the story of human behavior. You may be a big bunch of atoms governed by the mechanical laws, but you are not just any bunch of atoms. You are an intricately structured bunch of atoms, and your behavior depends not just on the laws that govern the individual atoms but on the way those atoms are assembled. At a higher level of description, your decisions can be truly open. When you walk into a store and choose between Android and Apple, the outcome is not preordained. It really is on you.

Skeptics miss this point, List argues, because they rely on loose intuitions about causation. They look for the causes of our actions in the basic laws of physics, yet the concept of cause does not even exist at that level, according to the broader theory of causation developed by computer scientist Judea Pearl and others. Causation is a higher-level concept. This theory is fully compatible with the view that humans and other agents are causal forces in the world. List’s book may not settle the debate—what could, after thousands of years?—but it will at least force skeptics to get more sophisticated in their own reasoning.

More here.

In Lucy Ives’s second novel, Loudermilk, a charismatic dumbass scams his way into a prestigious MFA poetry program by submitting the work of his antisocial companion. The real writer, who hates the sound of his own voice, follows the oversexed, symmetrically featured dumbass to school and continues to write for him. It’s a fun setup, but the book aims for more than just comedy. Ives, who once described herself as “the author of some kind of thinking about writing,” examines the conditions that produce authors and their work while never losing a sense of wonder at the sheer mystery of the written word.

In Lucy Ives’s second novel, Loudermilk, a charismatic dumbass scams his way into a prestigious MFA poetry program by submitting the work of his antisocial companion. The real writer, who hates the sound of his own voice, follows the oversexed, symmetrically featured dumbass to school and continues to write for him. It’s a fun setup, but the book aims for more than just comedy. Ives, who once described herself as “the author of some kind of thinking about writing,” examines the conditions that produce authors and their work while never losing a sense of wonder at the sheer mystery of the written word. The Internet was going to set us all free. At least, that is what U.S. policy makers, pundits, and scholars believed in the 2000s. The Internet would undermine authoritarian rulers by reducing the government’s stranglehold on debate, helping oppressed people realize how much they all hated their government, and simply making it easier and cheaper to organize protests.

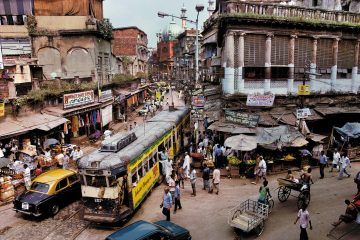

The Internet was going to set us all free. At least, that is what U.S. policy makers, pundits, and scholars believed in the 2000s. The Internet would undermine authoritarian rulers by reducing the government’s stranglehold on debate, helping oppressed people realize how much they all hated their government, and simply making it easier and cheaper to organize protests. In May 1975,

In May 1975,  Scientists have created the world’s first living organism that has a fully synthetic and radically altered DNA code.

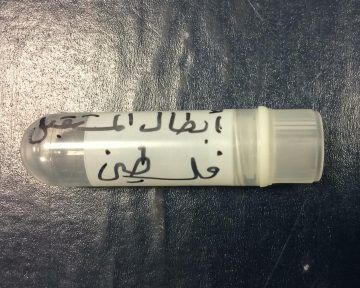

Scientists have created the world’s first living organism that has a fully synthetic and radically altered DNA code. Ashraf had been gone for more than a decade when he and Fat’hiya first heard about a fertility clinic in Ramallah that had begun helping the wives of Palestinian prisoners become pregnant with sperm smuggled out of Israeli jails. (Israeli prisoners are permitted conjugal visits; Palestinians are not.) The couple discussed it, Fat’hiya says, but neither of them was convinced it was a good idea.

Ashraf had been gone for more than a decade when he and Fat’hiya first heard about a fertility clinic in Ramallah that had begun helping the wives of Palestinian prisoners become pregnant with sperm smuggled out of Israeli jails. (Israeli prisoners are permitted conjugal visits; Palestinians are not.) The couple discussed it, Fat’hiya says, but neither of them was convinced it was a good idea.

In the first large-scale analysis of cancer gene fusions, which result from the merging of two previously separate genes, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, EMBL-EBI, Open Targets, GSK and their collaborators have used CRISPR to uncover which gene fusions are critical for the growth of cancer cells. The team also identified a new gene fusion that presents a novel drug target for multiple cancers, including brain and ovarian cancers. The results, published today (16 May) in Nature Communications, give more certainty for the use of specific

In the first large-scale analysis of cancer gene fusions, which result from the merging of two previously separate genes, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, EMBL-EBI, Open Targets, GSK and their collaborators have used CRISPR to uncover which gene fusions are critical for the growth of cancer cells. The team also identified a new gene fusion that presents a novel drug target for multiple cancers, including brain and ovarian cancers. The results, published today (16 May) in Nature Communications, give more certainty for the use of specific  Somewhat surprisingly, nature not only requires disorder but thrives on it. Planets, stars, life, even the direction of time all depend on disorder. And we human beings as well. Especially if, along with disorder, we group together such concepts as randomness, novelty, spontaneity, free will and unpredictability. We might put all of these ideas in the same psychic basket. Within the oppositional category of order, we can gather together notions such as systems, law, reason, rationality, pattern, predictability. While the different clusters of concepts are not mirror images of one another, like twilight and dawn, they have much in common.

Somewhat surprisingly, nature not only requires disorder but thrives on it. Planets, stars, life, even the direction of time all depend on disorder. And we human beings as well. Especially if, along with disorder, we group together such concepts as randomness, novelty, spontaneity, free will and unpredictability. We might put all of these ideas in the same psychic basket. Within the oppositional category of order, we can gather together notions such as systems, law, reason, rationality, pattern, predictability. While the different clusters of concepts are not mirror images of one another, like twilight and dawn, they have much in common. I’m going to go over a wide range of things that everyone will likely find something to disagree with. I want to start out by saying that I’m a materialist reductionist. As I talk, some people might get a little worried that I’m going off like Chalmers or something, but I’m not. I’m a materialist reductionist.

I’m going to go over a wide range of things that everyone will likely find something to disagree with. I want to start out by saying that I’m a materialist reductionist. As I talk, some people might get a little worried that I’m going off like Chalmers or something, but I’m not. I’m a materialist reductionist. I have been a professor at Harvard University for 34 years. In that time, the school has made some mistakes. But it has never so thoroughly embarrassed itself as it did this past weekend. At the center of the controversy is Ronald Sullivan, a law professor who ran afoul of student activists enraged that he was willing to represent Harvey Weinstein.

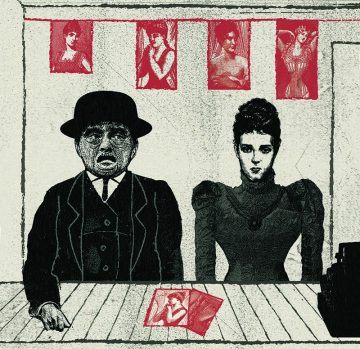

I have been a professor at Harvard University for 34 years. In that time, the school has made some mistakes. But it has never so thoroughly embarrassed itself as it did this past weekend. At the center of the controversy is Ronald Sullivan, a law professor who ran afoul of student activists enraged that he was willing to represent Harvey Weinstein. And it is here—at the level of physics—that the fates of the characters in The Secret Agent are truly decided: for they all—the criminal and the legitimate—run things too close, or simply let them fall. Conrad, surely, in his depiction of Verloc’s murder and its aftermath, surpassed all others—contemporary or otherwise—in his evocation of what it might be like to take a life, and the immediate psychic consequences for the killer: the complete and utter loneliness of Winnie Verloc after the murder is foreshadowed by this beautifully exact evocation of a psychic state, seen from within: “Her personality seemed to have been torn into two pieces, whose mental operations did not adjust themselves very well to each other.” A deracinated Polish aristocrat who tried to reinvent himself as a tweedy English country gentleman—the pseudonymous and multilingual Conrad knew all about being torn in pieces.

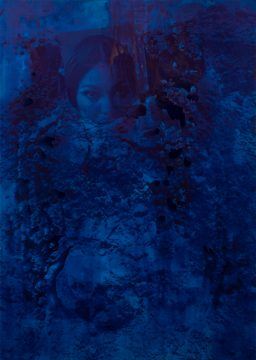

And it is here—at the level of physics—that the fates of the characters in The Secret Agent are truly decided: for they all—the criminal and the legitimate—run things too close, or simply let them fall. Conrad, surely, in his depiction of Verloc’s murder and its aftermath, surpassed all others—contemporary or otherwise—in his evocation of what it might be like to take a life, and the immediate psychic consequences for the killer: the complete and utter loneliness of Winnie Verloc after the murder is foreshadowed by this beautifully exact evocation of a psychic state, seen from within: “Her personality seemed to have been torn into two pieces, whose mental operations did not adjust themselves very well to each other.” A deracinated Polish aristocrat who tried to reinvent himself as a tweedy English country gentleman—the pseudonymous and multilingual Conrad knew all about being torn in pieces. The works in “Darkening,” a new exhibit of paintings by the artist Lorna Simpson, at Hauser & Wirth, are monumental panels that drown the viewer in blues—some shades so potent that they are black, purple. Using graduated saturations of ink-wash over gesso, Simpson builds landscapes and seascapes that recall J. M. W. Turner or Chinese shan shui compositions. But within these views of nature she plants artifacts of culture. Thin strips of what look like newspaper text are layered into a mountain in the painting “Blue Turned Temporal,” the meaning disintegrated. The heads and bodies of models from the pages of Ebony magazine are choked in inky waters. One day, not long ago, I lost myself staring into the series’ tallest work, “Specific Notation,” which, at twelve feet, threatens to reach the gallery’s ceiling. The lower two-thirds of the canvas feature circular stains that suggest underwater rock formations. Then, as if bursting from the mineral, the head of a woman appears suspended in the upper third of the frame, her face screwed into an expression of coy glowering. By the style of her hair, and by the manicuring of her eyebrows, we know that she is a figure of recent human history. But, in Simpson’s painting, frozen in the icy blue canvas, she seems eternal, outside of time.

The works in “Darkening,” a new exhibit of paintings by the artist Lorna Simpson, at Hauser & Wirth, are monumental panels that drown the viewer in blues—some shades so potent that they are black, purple. Using graduated saturations of ink-wash over gesso, Simpson builds landscapes and seascapes that recall J. M. W. Turner or Chinese shan shui compositions. But within these views of nature she plants artifacts of culture. Thin strips of what look like newspaper text are layered into a mountain in the painting “Blue Turned Temporal,” the meaning disintegrated. The heads and bodies of models from the pages of Ebony magazine are choked in inky waters. One day, not long ago, I lost myself staring into the series’ tallest work, “Specific Notation,” which, at twelve feet, threatens to reach the gallery’s ceiling. The lower two-thirds of the canvas feature circular stains that suggest underwater rock formations. Then, as if bursting from the mineral, the head of a woman appears suspended in the upper third of the frame, her face screwed into an expression of coy glowering. By the style of her hair, and by the manicuring of her eyebrows, we know that she is a figure of recent human history. But, in Simpson’s painting, frozen in the icy blue canvas, she seems eternal, outside of time. I

I In the summer of 1892 the poet

In the summer of 1892 the poet