Christof Koch in Nautilus:

The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

Compare this all-encompassing attitude of reverence to the historic view in the West. Abrahamic religions preach human exceptionalism—although animals have sensibilities, drives, and motivations and can act intelligently, they do not have an immortal soul that marks them as special, as able to be resurrected beyond history, in the Eschaton. On my travels and public talks, I still encounter plenty of scientists and others who, explicitly or implicitly, hold to human exclusivity. Cultural mores change slowly, and early childhood religious imprinting is powerful. I grew up in a devout Roman Catholic family with Purzel, a fearless dachshund. Purzel could be affectionate, curious, playful, aggressive, ashamed, or anxious. Yet my church taught that dogs do not have souls. Only humans do. Even as a child, I felt intuitively that this was wrong; either we all have souls, whatever that means, or none of us do.

René Descartes famously argued that a dog howling pitifully when hit by a carriage does not feel pain. The dog is simply a broken machine, devoid of the res cogitans or cognitive substance that is the hallmark of people. For those who argue that Descartes didn’t truly believe that dogs and other animals had no feelings, I present the fact that he, like other natural philosophers of his age, performed vivisection on rabbits and dogs. That’s live coronary surgery without anything to dull the agonizing pain. As much as I admire Descartes as a revolutionary thinker, I find this difficult to stomach.

More here.

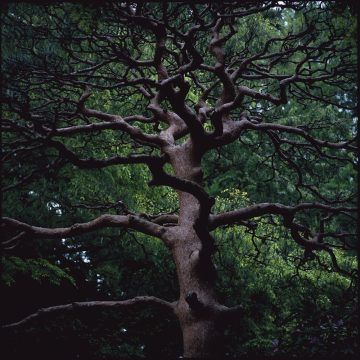

“[F]ungi are the grand recyclers of our planet,” writes mycologist Paul Stamets in Mycelium Running, “the mycomagicians disassembling large organic molecules into simpler forms, which in turn nourish other members of the ecological community.” Certain fungi, known as saprophytes (from the Greek sapro: “rotten” and phytes: “plants”), feed upon decaying or dead organic matter. These industrious mushrooms—portobello, cremini, oyster, reishi, enoki, royal trumpets, shiitake, white button—speed up decomposition, restore and aerate soil, and provide food for other life forms, from bacteria to bears. “The yeasts and molds used in making beer, wine, cheese, and bread are all saprophytes,” notes journalist and food writer Eugenia Bone in Mycophilia. So rot-eating fungi helped civilize us, Bone notes, “if you consider good wine an indicator of civilization.”

“[F]ungi are the grand recyclers of our planet,” writes mycologist Paul Stamets in Mycelium Running, “the mycomagicians disassembling large organic molecules into simpler forms, which in turn nourish other members of the ecological community.” Certain fungi, known as saprophytes (from the Greek sapro: “rotten” and phytes: “plants”), feed upon decaying or dead organic matter. These industrious mushrooms—portobello, cremini, oyster, reishi, enoki, royal trumpets, shiitake, white button—speed up decomposition, restore and aerate soil, and provide food for other life forms, from bacteria to bears. “The yeasts and molds used in making beer, wine, cheese, and bread are all saprophytes,” notes journalist and food writer Eugenia Bone in Mycophilia. So rot-eating fungi helped civilize us, Bone notes, “if you consider good wine an indicator of civilization.”

Among the memorable stories in Benjamin Moser’s engrossing, unsettling biography of

Among the memorable stories in Benjamin Moser’s engrossing, unsettling biography of  Nothing has better testified to the streak of illiberalism still coursing through Indian political life in the years since the Emergency than the documentaries of Anand Patwardhan. His target has shifted: from Gandhi’s supposedly liberal Congress Party to the rise of right-wing Hindu nationalism, now manifested by a BJP government whose prime minister, Narendra Modi, has turned Kashmir into a prison state and begun a mass expulsion of Muslims in Assam. But the form and political sensibility of Patwardhan’s work has remained: an engaged documentarian moving in contraflow to the ideas of the day.

Nothing has better testified to the streak of illiberalism still coursing through Indian political life in the years since the Emergency than the documentaries of Anand Patwardhan. His target has shifted: from Gandhi’s supposedly liberal Congress Party to the rise of right-wing Hindu nationalism, now manifested by a BJP government whose prime minister, Narendra Modi, has turned Kashmir into a prison state and begun a mass expulsion of Muslims in Assam. But the form and political sensibility of Patwardhan’s work has remained: an engaged documentarian moving in contraflow to the ideas of the day. In recent years, Jack Grieve of the department of English and linguistics at the University of Birmingham in England has embraced Twitter as a bountiful lode for looking at language-use patterns. One of his projects examined the regional popularity of profanity in the U.S. (“crap” is big in the center of the country; “f—” turns up more on the coasts).

In recent years, Jack Grieve of the department of English and linguistics at the University of Birmingham in England has embraced Twitter as a bountiful lode for looking at language-use patterns. One of his projects examined the regional popularity of profanity in the U.S. (“crap” is big in the center of the country; “f—” turns up more on the coasts).  It’s hot as fuck, said the friend who handed me Confessions Of The Fox, a faux-memoir set in eighteenth-century London. I was a little sceptical. After all, this was Jordy Rosenberg’s first novel. A queer theorist and historian of this period, he has re-written an eighteenth-century life from a trans perspective – a fool’s errand, murmured the cynic in me, to claim a world dominated by heteropatriarchy. Yet I found that as well as being hot as fuck, it was also something of a masterpiece.

It’s hot as fuck, said the friend who handed me Confessions Of The Fox, a faux-memoir set in eighteenth-century London. I was a little sceptical. After all, this was Jordy Rosenberg’s first novel. A queer theorist and historian of this period, he has re-written an eighteenth-century life from a trans perspective – a fool’s errand, murmured the cynic in me, to claim a world dominated by heteropatriarchy. Yet I found that as well as being hot as fuck, it was also something of a masterpiece. Like most people on Earth, Greta Thunberg is not a climate scientist. She has no formal scientific training of any type, nor does she possess any expert-level knowledge or expert-level skills in this regime. She has never worked on the problems or puzzles facing environmental scientists, atmospheric scientists, geophysicists, solar physicists, climatologists, meteorologists, or Earth scientists.

Like most people on Earth, Greta Thunberg is not a climate scientist. She has no formal scientific training of any type, nor does she possess any expert-level knowledge or expert-level skills in this regime. She has never worked on the problems or puzzles facing environmental scientists, atmospheric scientists, geophysicists, solar physicists, climatologists, meteorologists, or Earth scientists. Karachi feels like a city without a clearly defined past, or at least not one that has carried over into the present. In the 1950s it was known as the “Paris of the East,” but that impression has not aged well. In 1941, before partition, the city’s population was about 51% Hindu. Now it is virtually 0% Hindu, obliterating yet another feature of the city’s history. It is currently a mix of Pakistani ethnicities, including Sindhis (the home province), Punjabis, Pashtuns, the Baloch and many more — indeed, Pakistan in miniature.

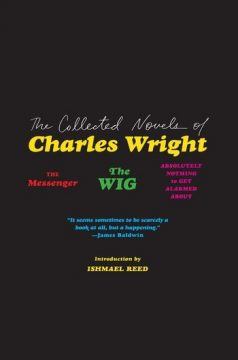

Karachi feels like a city without a clearly defined past, or at least not one that has carried over into the present. In the 1950s it was known as the “Paris of the East,” but that impression has not aged well. In 1941, before partition, the city’s population was about 51% Hindu. Now it is virtually 0% Hindu, obliterating yet another feature of the city’s history. It is currently a mix of Pakistani ethnicities, including Sindhis (the home province), Punjabis, Pashtuns, the Baloch and many more — indeed, Pakistan in miniature. The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s been enough. Through the dedication and (even) fervor of his steadfast readers, Wright’s sardonic, lyrical depictions of a young black intellectual’s odyssey through the lower depths of mid-twentieth-century New York City have somehow materialized in another century, much as Wright once imagined himself to move through time and space: “like an uncertain ghost through the white world.”

The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s been enough. Through the dedication and (even) fervor of his steadfast readers, Wright’s sardonic, lyrical depictions of a young black intellectual’s odyssey through the lower depths of mid-twentieth-century New York City have somehow materialized in another century, much as Wright once imagined himself to move through time and space: “like an uncertain ghost through the white world.” Gagliano concluded, in a

Gagliano concluded, in a  The truth about art theft in Europe – and Clerville is, among other things, a microcosm, or quintessence, of Europe – is less swashbuckling than most fiction. The exhibition halls at the Palazzo del Quirinale, spacious, sparsely decorated and a little flyblown, are exactly the sort of place where you can imagine Diabolik pulling off a caper, disguising himself as the President, say, or floating through the window on a jetpack. But the works on show in a minor blockbuster earlier this summer, all of it recovered by the TPC, had undergone various indignities that you’d struggle to turn into any kind of entertainment beyond a snuff movie. One masterpiece, a Hellenistic table support from Puglia in painted marble, representing two griffins lunching on a stag, had been hammered into pieces so it could be smuggled out of the country with a consignment of building materials. Three post-Impressionist paintings, smashed and grabbed from the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna twenty-one years ago, were destined for the bonfire, our guide said, if they couldn’t be consigned to their intended buyer. The “Senigallia Madonna” by Piero della Francesca, taken from the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino in 1975, was the subject of television appeals, like any kidnapping victim: “Please don’t touch her with your bare hands.” A stately, plump rococo cabinet had been cut down to fit a smaller space than that from which it had been untimely ripped.

The truth about art theft in Europe – and Clerville is, among other things, a microcosm, or quintessence, of Europe – is less swashbuckling than most fiction. The exhibition halls at the Palazzo del Quirinale, spacious, sparsely decorated and a little flyblown, are exactly the sort of place where you can imagine Diabolik pulling off a caper, disguising himself as the President, say, or floating through the window on a jetpack. But the works on show in a minor blockbuster earlier this summer, all of it recovered by the TPC, had undergone various indignities that you’d struggle to turn into any kind of entertainment beyond a snuff movie. One masterpiece, a Hellenistic table support from Puglia in painted marble, representing two griffins lunching on a stag, had been hammered into pieces so it could be smuggled out of the country with a consignment of building materials. Three post-Impressionist paintings, smashed and grabbed from the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna twenty-one years ago, were destined for the bonfire, our guide said, if they couldn’t be consigned to their intended buyer. The “Senigallia Madonna” by Piero della Francesca, taken from the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino in 1975, was the subject of television appeals, like any kidnapping victim: “Please don’t touch her with your bare hands.” A stately, plump rococo cabinet had been cut down to fit a smaller space than that from which it had been untimely ripped. The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious. Tucked away in Tokyo’s trendiest fashion district — two floors above a pricey French patisserie, and alongside nail salons and jewellers — the clinicians at Helene Clinic are infusing people with stem cells to treat cardiovascular disease. Smartly dressed female concierges with large bows on their collars shuttle Chinese medical tourists past an aquarium and into the clinic’s examination rooms.

Tucked away in Tokyo’s trendiest fashion district — two floors above a pricey French patisserie, and alongside nail salons and jewellers — the clinicians at Helene Clinic are infusing people with stem cells to treat cardiovascular disease. Smartly dressed female concierges with large bows on their collars shuttle Chinese medical tourists past an aquarium and into the clinic’s examination rooms. Since the upheavals of the financial crisis of 2008 and the political turbulence of 2016, it has become clear to many that liberalism is, in some sense, failing. The turmoil has given pause to economists, some of whom responded by renewing their study of inequality, and to political scientists, who have since turned to problems of democracy, authoritarianism, and populism in droves. But Anglo-American liberal political philosophers have had less to say than they might have.

Since the upheavals of the financial crisis of 2008 and the political turbulence of 2016, it has become clear to many that liberalism is, in some sense, failing. The turmoil has given pause to economists, some of whom responded by renewing their study of inequality, and to political scientists, who have since turned to problems of democracy, authoritarianism, and populism in droves. But Anglo-American liberal political philosophers have had less to say than they might have. Using a processor with programmable superconducting qubits, the Google team was able to run a computation in 200 seconds that they estimated the fastest supercomputer in the world would take 10,000 years to complete.

Using a processor with programmable superconducting qubits, the Google team was able to run a computation in 200 seconds that they estimated the fastest supercomputer in the world would take 10,000 years to complete. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that when Google

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that when Google