Category: Recommended Reading

How Ergodicity Reimagines Economics for The Benefit of Us All

Mark Buchanan at berfrois:

The upshot is that a subtle and mostly forgotten centuries-old choice in mathematical thinking has sent economics hurtling down a strange path. Only now are we beginning to learn how it might have been otherwise – and how a more realistic approach could help re-align economic orthodoxy with reality, to the benefit of all.

The upshot is that a subtle and mostly forgotten centuries-old choice in mathematical thinking has sent economics hurtling down a strange path. Only now are we beginning to learn how it might have been otherwise – and how a more realistic approach could help re-align economic orthodoxy with reality, to the benefit of all.

Of particular importance, the approach brings a new perspective to our understanding of cooperation and competition, and the conditions under which beneficial cooperative activity is possible. Standard thinking in economics finds limited scope for cooperation, as individual people or businesses seeking their own self-interest should cooperate only if, by working together, they can do better than by working alone. This is the case, for example, if the different parties have complementary skills or resources. In the absence of possibilities for beneficial exchange, it would make no sense for an agent with more resources to share or pool them together with an agent who has less.

more here.

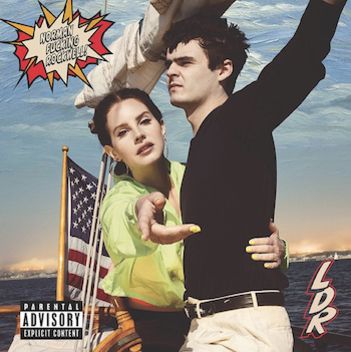

The Radical Empathy of Lana Del Rey

Quinn Roberts at the LARB:

In Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus called “Venice Bitch” the greatest California beach record of all time. To Marcus, the nine-minute rock ballad was languid and delicate, its production reminiscent of Randy Newman, the Beach Boys, the heyday of ’60s psychedelia. “It opens like a love letter,” he wrote, “prosaic, direct […] then a little more than two minutes in it begins to swirl, and you could be listening to an affair that began years ago or has yet to start.”

In Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus called “Venice Bitch” the greatest California beach record of all time. To Marcus, the nine-minute rock ballad was languid and delicate, its production reminiscent of Randy Newman, the Beach Boys, the heyday of ’60s psychedelia. “It opens like a love letter,” he wrote, “prosaic, direct […] then a little more than two minutes in it begins to swirl, and you could be listening to an affair that began years ago or has yet to start.”

According to the press, Lana Del Rey is changing — she’s grown-up, mature. She’s over the flower-crown stuff. For me, somebody whose affair with Lana began years ago, the recent praise comes as a great surprise. It seems like it was only yesterday that Pitchfork was comparing Born to Die to “a faked orgasm […] a collection of torch songs with no fire.” The critical notion of a “before and after” Lana is ultimately unrealistic. It fails to account for the tonal and thematic consistency of her oeuvre, which she has been fortifying since 2012.

more here.

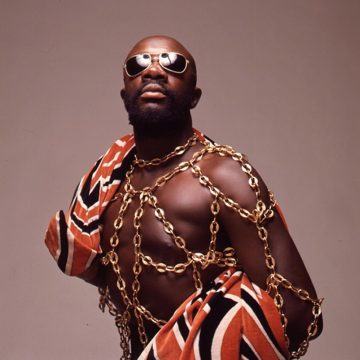

How Isaac Hayes Changed Soul Music

Emily Lordi at The New Yorker:

The meaning of Hayes’s music was similarly complex. But his seizure of musical space—literalized in the LP jacket for “Black Moses,” which unfolded to reveal a full-length portrait of Hayes in a robe, his arms outstretched—made a political statement at a time when black people were being made to feel acutely unwelcome in the public sphere: patrolled by police in their own neighborhoods, maimed and killed for being “in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Hayes took up time and space as if it were owed him, and listeners responded. “Hot Buttered Soul,” despite being what the critic Phyl Garland called “probably the strangest record hit of the year,” became the first Stax LP to go gold. It sold a million records to black consumers alone.

The meaning of Hayes’s music was similarly complex. But his seizure of musical space—literalized in the LP jacket for “Black Moses,” which unfolded to reveal a full-length portrait of Hayes in a robe, his arms outstretched—made a political statement at a time when black people were being made to feel acutely unwelcome in the public sphere: patrolled by police in their own neighborhoods, maimed and killed for being “in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Hayes took up time and space as if it were owed him, and listeners responded. “Hot Buttered Soul,” despite being what the critic Phyl Garland called “probably the strangest record hit of the year,” became the first Stax LP to go gold. It sold a million records to black consumers alone.

How exactly Hayes emerged from poverty and trauma to fashion himself so deeply at home in the world is one of the miracles of soul music. But, if the source of his confidence is mysterious, its destination is clear: Hayes’s audacious claims to space and selfhood are everywhere in hip-hop. Countless tracks, perhaps most notably Wu-Tang Clan’s “I Can’t Go to Sleep,” sample “Walk On By.”

more here.

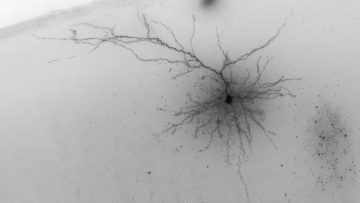

Scientists routinely cure brain disorders in mice but not us. A new study helps explain why

Sharon Begley in STAT News:

Lab mice endure a lot for science, but there’s often one (temporary) compensation: near-miraculous recovery from diseases that kill people. Unfortunately, experimental drugs that have cured millions of mice with Alzheimer’s disease or schizophrenia or glioblastoma have cured zero people — reflecting the sad fact that, for many brain disorders, mice are pretty lousy models of how humans will respond to a drug. Scientists have now discovered a key reason for that mouse-human disconnect, they reported on Wednesday: fundamental differences in the kinds of cells in each species’ cerebral cortex and, especially, in the activity of those cells’ key genes. In the most detailed taxonomy of the human brain to date, a team of researchers as large as a symphony orchestra sorted brain cells not by their shape and location, as scientists have done for decades, but by what genes they used. Among the key findings: Mouse and human neurons that have been considered to be the same based on such standard classification schemes can have large (tenfold or greater) differences in the expression of genes for such key brain components as neurotransmitter receptors.

Lab mice endure a lot for science, but there’s often one (temporary) compensation: near-miraculous recovery from diseases that kill people. Unfortunately, experimental drugs that have cured millions of mice with Alzheimer’s disease or schizophrenia or glioblastoma have cured zero people — reflecting the sad fact that, for many brain disorders, mice are pretty lousy models of how humans will respond to a drug. Scientists have now discovered a key reason for that mouse-human disconnect, they reported on Wednesday: fundamental differences in the kinds of cells in each species’ cerebral cortex and, especially, in the activity of those cells’ key genes. In the most detailed taxonomy of the human brain to date, a team of researchers as large as a symphony orchestra sorted brain cells not by their shape and location, as scientists have done for decades, but by what genes they used. Among the key findings: Mouse and human neurons that have been considered to be the same based on such standard classification schemes can have large (tenfold or greater) differences in the expression of genes for such key brain components as neurotransmitter receptors.

…Last year, scientists described neuropsychiatric drug development as “in the midst of a crisis” because of all the mouse findings that fail to translate to people. Of every 100 neuropsychiatric drugs tested in clinical trials — usually after they “work” in mice — only nine become approved medications, one of the lowest rates of all disease categories.

More here. (Note: Thanks to Dr. Abdullah Ali)

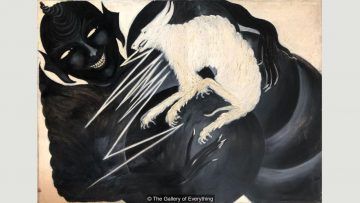

How Spiritualism invented modern art

Kelly Grovier in BBC News:

Every age invents the language that it needs. Posterity will determine what it says about our own era that we have felt compelled to craft such words and phrases as ‘defriended’, ‘photobomb’, ‘flash mob’, ‘happy slapping’ and ‘selfie’. When our forebears in the 1850s found themselves at a loss for a term to describe the new cultural phenomenon of holding seances to summon souls from the great beyond, it was a little-known writer, John Dix, who recorded the emergence of a fresh coinage: “Every two or three years,” Dix wrote in 1853, “the Americans have a paroxysm of humbug … at the present time it is Spiritual-ism”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Dix’s comment is the first published use of the word ‘Spiritualism’, in the sense of channelling voices and visions from an invisible realm. Despite Dix’s suggestion that Spiritualism was likely a fleeting fad (“a paroxysm of humbug”), the modern psyche had well and truly been bitten by the bug. Before long, the existence of spirits with whom it was possible to communicate in the here-and-now was being passionately investigated as plausible by everyone from the leading evolutionary scientist Alfred Russel Wallace (who was eventually convinced) to the celebrated novelist and champion of empirical deduction, Arthur Conan Doyle (who needed little persuading).

Every age invents the language that it needs. Posterity will determine what it says about our own era that we have felt compelled to craft such words and phrases as ‘defriended’, ‘photobomb’, ‘flash mob’, ‘happy slapping’ and ‘selfie’. When our forebears in the 1850s found themselves at a loss for a term to describe the new cultural phenomenon of holding seances to summon souls from the great beyond, it was a little-known writer, John Dix, who recorded the emergence of a fresh coinage: “Every two or three years,” Dix wrote in 1853, “the Americans have a paroxysm of humbug … at the present time it is Spiritual-ism”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Dix’s comment is the first published use of the word ‘Spiritualism’, in the sense of channelling voices and visions from an invisible realm. Despite Dix’s suggestion that Spiritualism was likely a fleeting fad (“a paroxysm of humbug”), the modern psyche had well and truly been bitten by the bug. Before long, the existence of spirits with whom it was possible to communicate in the here-and-now was being passionately investigated as plausible by everyone from the leading evolutionary scientist Alfred Russel Wallace (who was eventually convinced) to the celebrated novelist and champion of empirical deduction, Arthur Conan Doyle (who needed little persuading).

Over the course of the ensuing century, Spiritualism blossomed into a formidable force that shaped countless milestones of cultural expression: from the ‘automatic writings’ of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats to the so-called ‘New Music’ of the avant-garde US-Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg. In the visual arts, the spiritualist dimensions of certain painters is well established. Piet Mondrian once confessed that he “got everything” from the occultist writings of Madame Helena Blavatsky, founder of the mystical Theosophical Society, and Wassily Kandinsky published the seminal aesthetic treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art in 1911.

More here.

Exploring the brain in a new way: Researcher records neurons to understand cognition

Jack Stump in Phys.Org:

Where is Waldo?

Where is Waldo?

Whether we’re searching for Waldo or our keys in a room of clutter, we tap into a part of the frontal region of the brain when performing visual, goal-related tasks. Some of us do it well, whereas for others it’s a bit challenging. One West Virginia University researcher set out to investigate why, and what specifically this part of the brain, called the pre-supplementary motor area, does during searching.

To find out, Shuo Wang, assistant professor of chemical and biomedical engineering, took on the rare opportunity to record single neurons with electrodes implanted in epilepsy patients. He found neurons that signaled whether the target of a visual search was found and, if not, how long the patient had been searching for the item. This suggests that the pre-SMA contributes to goal-directed behavior by signaling goal detection and time elapsed since the start of a search, regardless of the task. It may be the first time scientists have identified neurons in the human pre-SMA that represent search goals, Wang said. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the cognitive aspects of disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia, which are linked to dysfunction of the pre-SMA, he said. Similarly, pre-SMA hyperactivity is a frequent observation in people with autism.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Bone of My Bone Flesh of My Flesh

I can’t always refer to the woman I love,

my children’s other mother,

as my darling, my beloved,

sugar in my bowl. No.

I need a common, utilitarian word

that calls no more attention to itself

than nouns like grass, bread, house.

The terms husband and wife are perfect for that.

Hassling with PG&E

or dropping off dry cleaning,

you don’t want to say,

The light of my life doesn’t like starch.

Don’t suggest spouse—a hideous word.

And partner is sterile as a boardroom.

Couldn’t we afford a term

for the woman who carried that girl in her arms

when she was still all promise,

that boy curled inside her womb?

And today, when I go to kiss her

and she says “Not now, I’m reading,”

still she deserves a syllable or two—if only

so I can express how furious

she makes me. But

maybe it’s better this way—

no puny pencil-stub of a word.

Maybe these are exactly the times

to drag out the whole galaxy

of endearments: Buttercup,

I should say, lambkin, mon petit chou.

by Ellen Bass

from The Human Line

Copper Canyon Press, 2007

Tuesday, October 1, 2019

What Was The Golden Age of TV?

Adam Wilson at Harper’s Magazine:

I’ll come back to The Sopranos, but first I want to discuss Bad-Good, an admittedly inelegant term for what the critic Dwight Macdonald called Midcult, which is not particularly elegant either. In his seminal 1960 essay “Masscult and Midcult,” Macdonald coined the word Masscult to describe popular forms—romance novels, Victorian Gothic architecture, the illustrations of Norman Rockwell—which he refused to dignify by classifying as culture. Macdonald’s chief concern was protecting high culture from the degradation of the marketplace, and to this end, he considered Masscult benign, too forthright in its motives to be mistaken for anything but commerce. He found a larger threat in Midcult, which was similar to Masscult except that it “pretends to respect the standards of High Culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them.” Midcult was Masscult masquerading as art.

I’ll come back to The Sopranos, but first I want to discuss Bad-Good, an admittedly inelegant term for what the critic Dwight Macdonald called Midcult, which is not particularly elegant either. In his seminal 1960 essay “Masscult and Midcult,” Macdonald coined the word Masscult to describe popular forms—romance novels, Victorian Gothic architecture, the illustrations of Norman Rockwell—which he refused to dignify by classifying as culture. Macdonald’s chief concern was protecting high culture from the degradation of the marketplace, and to this end, he considered Masscult benign, too forthright in its motives to be mistaken for anything but commerce. He found a larger threat in Midcult, which was similar to Masscult except that it “pretends to respect the standards of High Culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them.” Midcult was Masscult masquerading as art.

Television began as a strictly Masscult medium, and for most of its history remained indisputably so. In the Forties, the soap opera came to TV from radio as an instrument for selling cleaning products to housewives. The shows were produced by retail brands such as Procter and Gamble, and product promotions were woven directly into their story lines.

more here.

Serotonin By Michel Houellebecq

Houman Barekat at Literary Review:

That an author so notoriously sex-obsessed should concern himself with something as wholesome as ‘happiness’ looks, at first sight, like something of a contradiction. But Houellebecq was never really a hedonist. While often gratuitously graphic, his sex scenes are notably listless: related in blandly functional prose, they are conspicuously devoid of eroticism or joy. What some have interpreted as licentiousness could in fact be seen as the inverted prudery of the repressed social conservative. In Houellebecq’s fiction the libido, whether waxing or waning, is a problem to be overcome.

That an author so notoriously sex-obsessed should concern himself with something as wholesome as ‘happiness’ looks, at first sight, like something of a contradiction. But Houellebecq was never really a hedonist. While often gratuitously graphic, his sex scenes are notably listless: related in blandly functional prose, they are conspicuously devoid of eroticism or joy. What some have interpreted as licentiousness could in fact be seen as the inverted prudery of the repressed social conservative. In Houellebecq’s fiction the libido, whether waxing or waning, is a problem to be overcome.

In an essay published in Harper’s earlier this year, Houellebecq praised Donald Trump’s protectionist economic policies, describing his administration as a ‘necessary ordeal’, a corrective to the free market fundamentalism that has dominated Western politics for so long. His disaffected protagonists embody the impulse, common to Left and Right alike, to halt the juggernaut of unfettered globalisation.

more here.

A World Without Children

Samuel Scheffler in The Point:

My wife and I never spent much time talking about whether we wanted to have children. It was clear to both of us that we did, and our only concern was that we might not be able to. Yet if you had asked me why I wanted to have children, I would not have had anything very articulate to say. Nor did that fact bother me. Having children just seemed like the natural next step, and I felt no need to have or give reasons.

My wife and I never spent much time talking about whether we wanted to have children. It was clear to both of us that we did, and our only concern was that we might not be able to. Yet if you had asked me why I wanted to have children, I would not have had anything very articulate to say. Nor did that fact bother me. Having children just seemed like the natural next step, and I felt no need to have or give reasons.

For increasing numbers of people in developed countries, things are not so simple. The decision whether to have children is regarded as an important lifestyle choice. Many people choose not to have children, and they bristle at the description of themselves as “childless.” The preferred description is “childfree,” which suggests the absence of a burden (compare “carefree”) rather than a form of privation (compare “homeless,” “jobless” or “friendless”). Marketers regard two-career couples without children—or DINKS (dual-income, no kids), in the slang expression—as an attractive target demographic.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Will Wilkinson on Partisan Polarization and the Urban/Rural Divide

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

The idea of “red states” and “blue states” burst on the scene during the 2000 U.S. Presidential elections, and has a been a staple of political commentary ever since. But it’s become increasingly clear, and increasingly the case, that the real division isn’t between different sets of states, but between densely- and sparsely-populated areas. Cities are blue (liberal), suburbs and the countryside are red (conservative). Why did that happen? How does it depend on demographics, economics, and the personality types of individuals? I talk with policy analyst Will Wilkinson about where this division came from, and what it means for the future of the country and the world.

More here.

Is the United States on the brink of a revolution?

Serbulent Turan in The Conversation:

Of course, every revolution is unique and comparisons between them do not always yield useful insights. But there are a few criteria we identify in hindsight that are usually present in revolutionary explosions.

Of course, every revolution is unique and comparisons between them do not always yield useful insights. But there are a few criteria we identify in hindsight that are usually present in revolutionary explosions.

First, there’s tremendous economic inequality.

Second, there’s a deep conviction that the ruling classes serve only themselves at the expense of everyone else, undermining the belief that these inequalities will ever be addressed by the political elite.

Third, and somewhat in response to these, there is the rise of political alternatives that were barely acceptable in the margins of society before.

More here.

The Arc of Life: Roger Penrose

Stephen Hawking once said of his long-time friend and collaborator Roger Penrose: “although I’m regarded as a radical, I’m definitely a conservative compared to Roger”. Roger Penrose has made ground-breaking contributions to the fields of quantum gravity, general relativity, and cosmology. In this interview with filmmaker David Malone, Penrose looks back on his life’s work and shares new ideas on the subjects of logic and consciousness.

Who’s Afraid of Impeachment? On Presidential Investigation and a 2020 Backlash

Anthont Dimaggio in Counterpunch:

There has been quite a bit of prophesizing among pundits in the news media, on the right and elsewhere, and even among some on the left with which I’ve spoken, in which critics confidently maintain that impeachment is a “gift” to Trump, dividing the nation, but mobilizing and energizing Trump’s base, thereby handing the election to Trump. These claims are almost entirely based on fear and conjecture, not on actual evidence. If we look back to the limited history of this country’s use of impeachment against presidents in modern times, there is little evidence to draw from one way or another, and certainly no cases that are equivalent to this one, in terms of telling us how impeachment will impact an election that is so far into the future – an entire year from now.

There has been quite a bit of prophesizing among pundits in the news media, on the right and elsewhere, and even among some on the left with which I’ve spoken, in which critics confidently maintain that impeachment is a “gift” to Trump, dividing the nation, but mobilizing and energizing Trump’s base, thereby handing the election to Trump. These claims are almost entirely based on fear and conjecture, not on actual evidence. If we look back to the limited history of this country’s use of impeachment against presidents in modern times, there is little evidence to draw from one way or another, and certainly no cases that are equivalent to this one, in terms of telling us how impeachment will impact an election that is so far into the future – an entire year from now.

Conceding the uncertainty associated with the inquiry against Trump, available evidence suggests there is little reason to be engaging in fearmongering on impeachment. Going back to the looming impeachment of Richard Nixon following the emergence of the Watergate scandal, we see no evidence that the removal strategy harmed Democrats. Republicans lost 49 seats in the House in 1974, while losing another 5 in the Senate. Gerald Ford’s reputation – as measured by his job approval rating – quickly nosedived following his pardon of Nixon, and Jimmy Carter won the 1976 election, defeating Ford, while Democrats gained a seat in the House of Representatives, while losing one seat in the Senate. In other words, there were no observable repercussions for the Democrats for forcing Nixon from office.

More here.

These Ants Use Germ-Killers, and They’re Better Than Ours

Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

As a microbiologist, Massimiliano Marvasi has spent years studying how microbes have defeated us. Many pathogens have evolved resistance to penicillin and other antimicrobial drugs, and now public health experts are warning of a global crisis in treating infectious diseases. These days, Dr. Marvasi, a senior researcher at the University of Florence in Italy, finds solace in studying ants. About 240 species of ants grow underground gardens of fungi. They protect their farms against pathogens using powerful chemicals secreted by bacteria on their bodies. Unlike humans, ants are not facing a crisis of antimicrobial resistance. Writing in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Dr. Marvasi and his colleagues argue that fungus-farming ants could serve as a model for drug development. It’s not just that they have antimicrobials — it’s how they use their drugs.

As a microbiologist, Massimiliano Marvasi has spent years studying how microbes have defeated us. Many pathogens have evolved resistance to penicillin and other antimicrobial drugs, and now public health experts are warning of a global crisis in treating infectious diseases. These days, Dr. Marvasi, a senior researcher at the University of Florence in Italy, finds solace in studying ants. About 240 species of ants grow underground gardens of fungi. They protect their farms against pathogens using powerful chemicals secreted by bacteria on their bodies. Unlike humans, ants are not facing a crisis of antimicrobial resistance. Writing in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Dr. Marvasi and his colleagues argue that fungus-farming ants could serve as a model for drug development. It’s not just that they have antimicrobials — it’s how they use their drugs.

Fungus-farming ants bring leaves or other debris to gardens in their nests, where certain kinds of fungi thrive. The fungi — which can flourish nowhere else — grow into dense webs that the ants feed to their larvae. But the crops are also attractive to a parasitic fungus called Escovopsis. It attacks the gardens and starves the ants. “It’s a war between the ants and the pathogens for the same food,” Dr. Marvasi said. The ants have powerful allies in this war: bacteria that live on their thoraxes. Worker ants coat eggs with certain strains of these bacteria. As an ant matures, it feeds its personal supply of bacteria with secretions from glands on its thorax. The bacteria pay the ants back for this special care by making powerful antimicrobials that kill Escovopsis, protecting the gardens from destruction.

The fact that bacteria make antimicrobials is hardly surprising. The ones that doctors prescribe today were mostly discovered in the soil, made by microbes. What is surprising is that the chemicals used by the ants work so well.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Praying the Hours At Elkhorn Slough

God. Ocean. Sunrise.

Whatever I am sitting here between,

hello.

Sea otter profile:

backcurved, hooking the tide.

Nothing so distinctive

–so joyfully learned, wondrously greeted

every salt-gift sighting.

Lowtide wader talk.

Coyote brush sun-scented

and the seals hauled out.

My low tide too

but the breeze coming up says

wake. Pray

with one foot

steady-placed, and then

the other.

Something has died. And the pleasant smell

of chaparral cannot hope to cover it up.

The chaparral must die and so must I

–would we not also wish

to leave something behind?

At the last, four notes

ascending their purple staff:

marsh-water-dune-sky.

After the last

……… silent owl-rise.

by Tara K. Shepersky

from Echotheo Review

9/18/19

Sunday, September 29, 2019

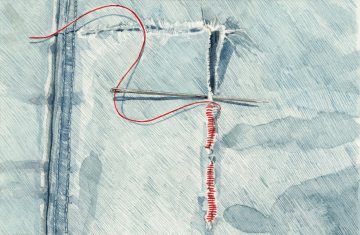

The antidote to endless, thoughtless consumption lies not in purging ourselves of the stuff we own, but rather, redefining our relationship with stuff altogether

Benjamin Leszcz in The Globe and Mail:

Several years ago, while living in London, England, my wife met Prince Charles at an event associated with the Prince’s Foundation, where she worked. She returned with two observations: First, the Prince of Wales used two fingers – index and middle – when he pointed. Second, Charles’s suit had visible signs of mending. A Google search fails to substantiate the double-barrelled gesture, but the Prince’s penchant for patching has been well documented. Last year, the journalist Marion Hume discovered a cardboard box containing more than 30 years of off-cuts and leftover materials from the Prince’s suits, tucked away in a corner at his Savile Row tailor, Anderson & Sheppard. “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible … through patches and repairs,” he told Ms. Hume. “In this way, I tend to be in fashion once every 25 years.”

Several years ago, while living in London, England, my wife met Prince Charles at an event associated with the Prince’s Foundation, where she worked. She returned with two observations: First, the Prince of Wales used two fingers – index and middle – when he pointed. Second, Charles’s suit had visible signs of mending. A Google search fails to substantiate the double-barrelled gesture, but the Prince’s penchant for patching has been well documented. Last year, the journalist Marion Hume discovered a cardboard box containing more than 30 years of off-cuts and leftover materials from the Prince’s suits, tucked away in a corner at his Savile Row tailor, Anderson & Sheppard. “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible … through patches and repairs,” he told Ms. Hume. “In this way, I tend to be in fashion once every 25 years.”

As it happens, double-breasted suits are rather on-trend. But more notable is Charles’s sartorial philosophy, which could not be timelier. The Prince comes from a tradition of admirable frugality – the Queen reuses gift-wrap – but his inclination to repair rather than replace, to wear his clothes until they wear out, is an apt antidote to our increasingly disposable times. Most modern consumers are not nearly so resourceful: The average Canadian buys 70 new pieces of clothing each year, about 60 of which ultimately wind up in a landfill.

More here.

On the Evolution of Animal Consciousness

Michael S. A. Graziano in Literary Hub:

Self-replicating, bacterial life first appeared on Earth about 4 billion years ago. For most of Earth’s history, life remained at the single-celled level, and nothing like a nervous system existed until around 600 or 700 million years ago (MYA). In the attention schema theory, consciousness depends on the nervous system processing information in a specific way. The key to the theory, and I suspect the key to any advanced intelligence, is attention—the ability of the brain to focus its limited resources on a restricted piece of the world at any one time in order to process it in greater depth.

Self-replicating, bacterial life first appeared on Earth about 4 billion years ago. For most of Earth’s history, life remained at the single-celled level, and nothing like a nervous system existed until around 600 or 700 million years ago (MYA). In the attention schema theory, consciousness depends on the nervous system processing information in a specific way. The key to the theory, and I suspect the key to any advanced intelligence, is attention—the ability of the brain to focus its limited resources on a restricted piece of the world at any one time in order to process it in greater depth.

I will begin the story with sea sponges, because they help to bracket the evolution of the nervous system. They are the most primitive of all multicellular animals, with no overall body plan, no limbs, no muscles, and no need for nerves. They sit at the bottom of the ocean, filtering nutrients like a sieve. And yet sponges do share some genes with us, including at least 25 that, in people, help structure the nervous system. In sponges, the same genes may be involved in simpler aspects of how cells communicate with each other. Sponges seem to be poised right at the evolutionary threshold of the nervous system. They are thought to have shared a last common ancestor with us between about 700 and 600 MYA.

More here.

How The U.S. Hacked ISIS

Dina Temple-Raston at NPR:

The crowded room was awaiting one word: “Fire.”

The crowded room was awaiting one word: “Fire.”

Everyone was in uniform; there were scheduled briefings, last-minute discussions, final rehearsals. “They wanted to look me in the eye and say, ‘Are you sure this is going to work?’ ” an operator named Neil said. “Every time, I had to say yes, no matter what I thought.” He was nervous, but confident. U.S. Cyber Command and the National Security Agency had never worked together on something this big before.

Four teams sat at workstations set up like high school carrels. Sergeants sat before keyboards; intelligence analysts on one side, linguists and support staff on another. Each station was armed with four flat-screen computer monitors on adjustable arms and a pile of target lists and IP addresses and online aliases. They were cyberwarriors, and they all sat in the kind of oversize office chairs Internet gamers settle into before a long night.

“I felt like there were over 80 people in the room, between the teams and then everybody lining the back wall that wanted to watch,” Neil recalled. He asked us to use only his first name to protect his identity. “I’m not sure how many people there were on the phones listening in or in chat rooms.”

More here.