Bradley Van Paridon in Chemistry World:

A chance decision to attend a lecture led to the discovery of an elusive protein and promising drug target for parasites causing some of the world’s most notorious neglected tropical diseases – Chagas disease, sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis. As this protein had been so slippery and hard to track down some had doubted that it even existed in these parasites at all.

A chance decision to attend a lecture led to the discovery of an elusive protein and promising drug target for parasites causing some of the world’s most notorious neglected tropical diseases – Chagas disease, sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis. As this protein had been so slippery and hard to track down some had doubted that it even existed in these parasites at all.

Trypanosomes are a group of protozoan parasites transmitted by insect bites that cause sickness, morbidity and death in humans and livestock in developing countries. They are responsible for sickening millions of people every year and cause the deaths of tens of thousands of those infected, but the diseases these parasites cause do not receive the attention others do as they mostly affect poorer people in the Global South.

For decades trypanosome researchers have searched for a protein called Pex3 within the genomes of trypanosomes.

More here.

“In the United

“In the United  In the annals of disastrous musical premieres, that of Edward Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, which took place on this date in 1900, wasn’t a complete fiasco in the manner of, say, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or Bruckner’s Third Symphony. It did not, however, go well—not by any measure. So poor was the performance, so distant the musicians’ execution from Elgar’s most vivid and hopeful imagining, that the experience left the composer despondent. A devout Catholic, he even briefly lost his faith.

In the annals of disastrous musical premieres, that of Edward Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, which took place on this date in 1900, wasn’t a complete fiasco in the manner of, say, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or Bruckner’s Third Symphony. It did not, however, go well—not by any measure. So poor was the performance, so distant the musicians’ execution from Elgar’s most vivid and hopeful imagining, that the experience left the composer despondent. A devout Catholic, he even briefly lost his faith. A series of discoveries, each disturbing in turn, leads to Snowden’s eventual decision to stockpile documents, smuggle them out of the Hawaiian bunker where he works for the NSA, and flee with them to Hong Kong, where he would meet the documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill. One such discovery was that of Stellar Wind, a bulk surveillance program that previous NSA whistleblowers had tried to warn lawmakers about. Through these and other programs, through the building of an unprecedentedly massive data center in Utah, through the boasts of a CIA technologist who talks about collecting and computing on all information generated in the world, Snowden begins to understand that “surveillance wasn’t something occasional and directed in legally justified circumstances, but a constant and indiscriminate presence . . . a memory that is sleepless and permanent.” The machine reaches everywhere, collapsing space, time, and memory into a single archive. “I now understood that I was totally transparent to my government,” he acknowledges with the finality of someone accepting a cancer diagnosis. Even the promises of free speech become illusory under the surveillance regime, as “self-expression now required such strong self-protection as to obviate its liberties and nullify its pleasures.”

A series of discoveries, each disturbing in turn, leads to Snowden’s eventual decision to stockpile documents, smuggle them out of the Hawaiian bunker where he works for the NSA, and flee with them to Hong Kong, where he would meet the documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill. One such discovery was that of Stellar Wind, a bulk surveillance program that previous NSA whistleblowers had tried to warn lawmakers about. Through these and other programs, through the building of an unprecedentedly massive data center in Utah, through the boasts of a CIA technologist who talks about collecting and computing on all information generated in the world, Snowden begins to understand that “surveillance wasn’t something occasional and directed in legally justified circumstances, but a constant and indiscriminate presence . . . a memory that is sleepless and permanent.” The machine reaches everywhere, collapsing space, time, and memory into a single archive. “I now understood that I was totally transparent to my government,” he acknowledges with the finality of someone accepting a cancer diagnosis. Even the promises of free speech become illusory under the surveillance regime, as “self-expression now required such strong self-protection as to obviate its liberties and nullify its pleasures.” Stendhal didn’t like Vilna, either.

Stendhal didn’t like Vilna, either. Females of O. pumilio lay eggs on the ground, on a leaf covered by other foliage, where they are fertilized by the male. During the following week, the male ensures that the eggs stay wet, and after the eggs have hatched, the female takes over the parental care. She carries each tadpole on her back (Fig. 1) to a water-filled bromeliad plant, and then returns to feed the tadpole with her unfertilized eggs until it is sexually mature. The authors studied three colour types of O. pumilio, and carried out laboratory experiments involving three set-ups: tadpoles were raised by their biological parents, which were both the same colour; they were raised by their parents, which were of different colours; or they were raised by foster frogs that were not the same colour as the tadpoles’ parents. For all three scenarios, when the female tadpoles became adults, female offspring preferred to mate with males of the same colour as the mother that had reared them.

Females of O. pumilio lay eggs on the ground, on a leaf covered by other foliage, where they are fertilized by the male. During the following week, the male ensures that the eggs stay wet, and after the eggs have hatched, the female takes over the parental care. She carries each tadpole on her back (Fig. 1) to a water-filled bromeliad plant, and then returns to feed the tadpole with her unfertilized eggs until it is sexually mature. The authors studied three colour types of O. pumilio, and carried out laboratory experiments involving three set-ups: tadpoles were raised by their biological parents, which were both the same colour; they were raised by their parents, which were of different colours; or they were raised by foster frogs that were not the same colour as the tadpoles’ parents. For all three scenarios, when the female tadpoles became adults, female offspring preferred to mate with males of the same colour as the mother that had reared them. For nine weeks in late 1888, two of art’s great loners lived together. The home and studio Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh shared was the small and unassuming “Yellow House”, just outside the northern city gate of Arles in the south of France. There was an imbalance to the arrangement. Van Gogh thought the older man, a painter he adulated, had arrived from Paris to help him realise his dream of creating an artists’ haven, a “studio in the south”; Gauguin was in fact paid by Theo van Gogh, a successful art dealer and the white sheep of the family, to act as painter-chaperone to his troubled brother.

For nine weeks in late 1888, two of art’s great loners lived together. The home and studio Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh shared was the small and unassuming “Yellow House”, just outside the northern city gate of Arles in the south of France. There was an imbalance to the arrangement. Van Gogh thought the older man, a painter he adulated, had arrived from Paris to help him realise his dream of creating an artists’ haven, a “studio in the south”; Gauguin was in fact paid by Theo van Gogh, a successful art dealer and the white sheep of the family, to act as painter-chaperone to his troubled brother. One of the reasons nations fail to address climate change is the belief that we can have infinite economic growth independent of ecosystem sustainability. Extreme weather events, melting arctic ice, and species extinction expose the lie that growth can forever be prioritized over planetary boundaries.

One of the reasons nations fail to address climate change is the belief that we can have infinite economic growth independent of ecosystem sustainability. Extreme weather events, melting arctic ice, and species extinction expose the lie that growth can forever be prioritized over planetary boundaries. The biological species concept states that species are reproductively isolated entities – that is, they breed within themselves but not with other species. Thus all living Homo sapiens have the potential to breed with each other, but could not successfully interbreed with gorillas or chimpanzees, our closest living relatives.

The biological species concept states that species are reproductively isolated entities – that is, they breed within themselves but not with other species. Thus all living Homo sapiens have the potential to breed with each other, but could not successfully interbreed with gorillas or chimpanzees, our closest living relatives. On a recent sun-drenched afternoon, I was wandering the leafy blocks of West 82nd Street near Central Park, when I came to number 155, a stately Victorian brownstone with a carved stone stoop. Not so different from 1,000 other addresses on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I thought – except that this is where the young Fidel Castro, a then-unknown 22-year-old Cuban law graduate, stayed on his honeymoon in 1948.

On a recent sun-drenched afternoon, I was wandering the leafy blocks of West 82nd Street near Central Park, when I came to number 155, a stately Victorian brownstone with a carved stone stoop. Not so different from 1,000 other addresses on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I thought – except that this is where the young Fidel Castro, a then-unknown 22-year-old Cuban law graduate, stayed on his honeymoon in 1948. Is modern-day philanthropy a disease in the democratic body politic? Rob Reich, a professor of political science at Stanford University (not to be confused with former secretary of labor Robert Reich), believes that it is. And Reich is not alone. Near-universal outrage over the recent college admissions scandal has left two black eyes on American philanthropy: one for the role of Rick Singer’s fraudulent 501(c)(3) organization, Key Worldwide Foundation, in bribing several elite universities to accept children of privilege; the other for the universities’ susceptibility to such schemes. Reich’s book went to press well before the scandal broke, but it is hard to imagine a better indication of his central claim: that philanthropy amplifies the power of the few at the expense of the many.

Is modern-day philanthropy a disease in the democratic body politic? Rob Reich, a professor of political science at Stanford University (not to be confused with former secretary of labor Robert Reich), believes that it is. And Reich is not alone. Near-universal outrage over the recent college admissions scandal has left two black eyes on American philanthropy: one for the role of Rick Singer’s fraudulent 501(c)(3) organization, Key Worldwide Foundation, in bribing several elite universities to accept children of privilege; the other for the universities’ susceptibility to such schemes. Reich’s book went to press well before the scandal broke, but it is hard to imagine a better indication of his central claim: that philanthropy amplifies the power of the few at the expense of the many. The lectures reveal the various themes and preoccupations in Foucault’s work in the 1970s and 80s; they also help to contextualize many of the changes in his thought. Still, it is difficult to characterize Foucault’s work. He often denied that he was a theorist, by which he meant someone who works within an overarching system. Describing himself as an experimenter, Foucault frequently underscored the tentative and fragmentary nature of his research. His work is also anti-systematic in the sense that it explores the logic of specific mechanisms, technologies and strategies of power. This exploration requires that close attention be paid to historical conditions whose singularity defies subsumption under a universal history. But Foucault’s antipathy towards systematic thought also meant that he enthusiastically pursued new directions in his research (his later study of care of the self in ancient Greece and Hellenistic Rome is a case in point), and he readily acknowledged the disparities between his earlier and later work.

The lectures reveal the various themes and preoccupations in Foucault’s work in the 1970s and 80s; they also help to contextualize many of the changes in his thought. Still, it is difficult to characterize Foucault’s work. He often denied that he was a theorist, by which he meant someone who works within an overarching system. Describing himself as an experimenter, Foucault frequently underscored the tentative and fragmentary nature of his research. His work is also anti-systematic in the sense that it explores the logic of specific mechanisms, technologies and strategies of power. This exploration requires that close attention be paid to historical conditions whose singularity defies subsumption under a universal history. But Foucault’s antipathy towards systematic thought also meant that he enthusiastically pursued new directions in his research (his later study of care of the self in ancient Greece and Hellenistic Rome is a case in point), and he readily acknowledged the disparities between his earlier and later work. Great sculptors are rare and strange. In Western art, whole eras have gone by without one, and one at a time is how these artists come. I mean sculptors who epitomize their epochs in three dimensions that acquire the fourth, of time, in the course of our fascination. There’s always something disruptive—uncalled for—about them. Their effects partake in a variant of the sublime that I experience as, roughly, beauty combined with something unpleasant. I think of the marble carvings of Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome: the Baroque done to everlasting death. A feeling of excess in both form and fantasy may be disagreeable—there’s so much going on as Daphne morphs into a tree to escape Apollo, or a delighted seraph stabs an ecstatic St. Teresa in the heart with an arrow. But try to detect an extraneous curlicue or an unpersuasive gesture. Everything works! Move around. A newly magnificent unity coalesces at each step. You’re knocked sideways out of comparisons to other art in any medium or genre. Four centuries of intervening history evaporate. Being present in the body is crucial to beholding Bernini’s incarnations. Painting can’t compete with this total engagement. It doesn’t need to, because great sculpture is so difficult and, in each instance, so particular and even bizarre.

Great sculptors are rare and strange. In Western art, whole eras have gone by without one, and one at a time is how these artists come. I mean sculptors who epitomize their epochs in three dimensions that acquire the fourth, of time, in the course of our fascination. There’s always something disruptive—uncalled for—about them. Their effects partake in a variant of the sublime that I experience as, roughly, beauty combined with something unpleasant. I think of the marble carvings of Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome: the Baroque done to everlasting death. A feeling of excess in both form and fantasy may be disagreeable—there’s so much going on as Daphne morphs into a tree to escape Apollo, or a delighted seraph stabs an ecstatic St. Teresa in the heart with an arrow. But try to detect an extraneous curlicue or an unpersuasive gesture. Everything works! Move around. A newly magnificent unity coalesces at each step. You’re knocked sideways out of comparisons to other art in any medium or genre. Four centuries of intervening history evaporate. Being present in the body is crucial to beholding Bernini’s incarnations. Painting can’t compete with this total engagement. It doesn’t need to, because great sculpture is so difficult and, in each instance, so particular and even bizarre. In one type of cancer immunotherapy, immune cells called T cells are removed from the body and engineered to target cells that are only found in cancers. The engineered cells, called chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts), have proved exceedingly effective against some types of blood cancers, particularly acute lymphocytic leukemia. Scientists have now started engineering T cells to attack other disease-related cells.

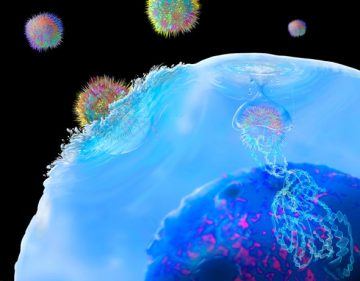

In one type of cancer immunotherapy, immune cells called T cells are removed from the body and engineered to target cells that are only found in cancers. The engineered cells, called chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts), have proved exceedingly effective against some types of blood cancers, particularly acute lymphocytic leukemia. Scientists have now started engineering T cells to attack other disease-related cells. Sugar isn’t just for sweets. Inside cells, sugars attached to proteins and fats help molecules recognize one another—and let cells communicate. Now, for the first time, researchers report that sugars also appear to bind to some RNA molecules, the cellular workhorses that do everything from translating DNA into proteins to catalyzing chemical reactions. It’s unclear just what these sugar-coated RNAs do. But if the result holds up, it suggests vast new roles for RNA.

Sugar isn’t just for sweets. Inside cells, sugars attached to proteins and fats help molecules recognize one another—and let cells communicate. Now, for the first time, researchers report that sugars also appear to bind to some RNA molecules, the cellular workhorses that do everything from translating DNA into proteins to catalyzing chemical reactions. It’s unclear just what these sugar-coated RNAs do. But if the result holds up, it suggests vast new roles for RNA. Imagine you’re driving a trolley car. Suddenly the brakes fail, and on the track ahead of you are five workers you’ll run over. Now, you can steer onto another track, but on that track is one person who you will kill instead of the five: It’s the difference between unintentionally killing five people versus intentionally killing one.

Imagine you’re driving a trolley car. Suddenly the brakes fail, and on the track ahead of you are five workers you’ll run over. Now, you can steer onto another track, but on that track is one person who you will kill instead of the five: It’s the difference between unintentionally killing five people versus intentionally killing one.  Anne Carson 4/1

Anne Carson 4/1