Branko Milanovic over at his website:

Branko Milanovic over at his website:

It seems obvious. Let me start with the definitions that economists who work on inequality use. It is the sum total of all assets that you own (cash, house, car, furniture, paintings, money in the bank, value of shares, bonds etc.) plus what is called “the surrender value” of life insurance and similar plans minus the amount of your debts. In other words, this is the amount of money that you would get if you had to liquidate today all your possessions and repay all your debts. (The amount can clearly be negative too.) The definition can get further complicated as some economists insist that we should also add the capitalized value of future (certain?) streams of income. That leads to the problems that I explained here—but be this as it may, in this post I would like to take a more historical view of wealth.

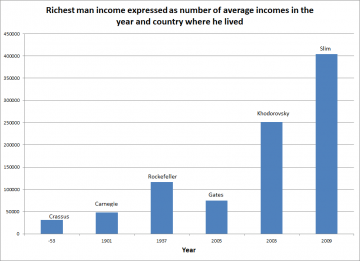

I did that too in my “The Haves and the Have-nots” when I discussed who might have been the richest person in history. If you want to compare people from different epochs you cannot just simply try to calculate their total wealth. That is impossible because of what is known as the “index number problem”: there is no way to compare the bundle of goods and services which are hugely dissimilar. If I can listen to a million songs and read the whole night using a very good light, and if I put a high value on that, I may be thought to be wealthier than any king who lived 1000 years ago. Tocqueville noticed that too when he wrote that ancient kings lived lives of luxury but not comfort.

This is why we should use Adam Smith’s definition of wealth: “[A person] must be rich or poor according to the quantity of labor which he can command”.

More here.