Jeannette Cooperman at The Common Reader:

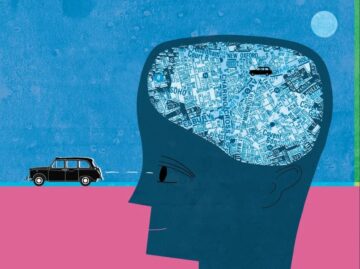

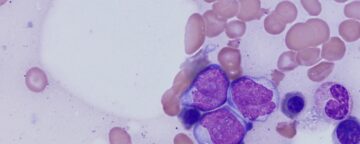

A pandemic is never only about biological contagion. Much of what we feel, think, and do—far more than I want to admit—is the product of what we perceive or unconsciously mimic in the world around us. Laughter is contagious, and yawns—even chimpanzees find yawns contagious. I realize only now, in the enforced quiet, how I absorbed the pace and values of the society around me. My mind was quiet, if concerned, as I watched the infectiousness of fear, panic, and hysteria; of rationalization or mystification; of courage. Ideas and beliefs, good information and bad information, enthusiasm and advice and funny memes spread as fast as the virus.

A pandemic is never only about biological contagion. Much of what we feel, think, and do—far more than I want to admit—is the product of what we perceive or unconsciously mimic in the world around us. Laughter is contagious, and yawns—even chimpanzees find yawns contagious. I realize only now, in the enforced quiet, how I absorbed the pace and values of the society around me. My mind was quiet, if concerned, as I watched the infectiousness of fear, panic, and hysteria; of rationalization or mystification; of courage. Ideas and beliefs, good information and bad information, enthusiasm and advice and funny memes spread as fast as the virus.

All of that is contagion.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The system, called AlphaEvolve, combines the creativity of a large language model (LLM) with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. It was described in a white paper

The system, called AlphaEvolve, combines the creativity of a large language model (LLM) with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. It was described in a white paper  One of the most intriguing ways of conceptualizing the scorched landscape of the 2020s is the theory of ‘hyperpolitics’, advanced by the Belgian political philosopher Anton Jäger. Our current predicament, he writes, is one of “extreme politicization without political consequences.” While ideological commitment is ubiquitous, institutional outlets for it are absent. While contestation is fierce, the form it takes is frustratingly ephemeral. Politics is at once everywhere and nowhere – permeating our everyday lives but failing to influence state policy, which continues on much the same neoliberal trajectory, with minor variations here and there.

One of the most intriguing ways of conceptualizing the scorched landscape of the 2020s is the theory of ‘hyperpolitics’, advanced by the Belgian political philosopher Anton Jäger. Our current predicament, he writes, is one of “extreme politicization without political consequences.” While ideological commitment is ubiquitous, institutional outlets for it are absent. While contestation is fierce, the form it takes is frustratingly ephemeral. Politics is at once everywhere and nowhere – permeating our everyday lives but failing to influence state policy, which continues on much the same neoliberal trajectory, with minor variations here and there. London cabbies

London cabbies In April 2024, Favreau visited the White House with his podcast co-hosts and several other “influencers” at a meet-and-greet the night before the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Biden was incoherent and frail; he kept telling stories that no one could understand. Sixteen months had passed, but he seemed to have aged a half-century. An alarmed Favreau approached a White House aide, but his concerns were brushed off. The president was just tired, he was told. It was the end of a long week. There was no reason for concern. Two months later, Biden delivered the single worst performance in the 60-year history of televised presidential debates, dooming his reelection campaign, destroying his presidency and essentially delivering the country to Donald Trump.

In April 2024, Favreau visited the White House with his podcast co-hosts and several other “influencers” at a meet-and-greet the night before the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Biden was incoherent and frail; he kept telling stories that no one could understand. Sixteen months had passed, but he seemed to have aged a half-century. An alarmed Favreau approached a White House aide, but his concerns were brushed off. The president was just tired, he was told. It was the end of a long week. There was no reason for concern. Two months later, Biden delivered the single worst performance in the 60-year history of televised presidential debates, dooming his reelection campaign, destroying his presidency and essentially delivering the country to Donald Trump. On a spring day in 1989, a container ship arrived in New York harbor from Eemshaven, a deepwater port in the Netherlands. The Vessel, named the Bibby Resolution, belonged to a well-established Liverpool shipping line, one whose founder had invested in the Atlantic slave trade two hundred years before. But while the company that owned it had a history that went back centuries, the ship itself was unmistakably a product of the late twentieth century.

On a spring day in 1989, a container ship arrived in New York harbor from Eemshaven, a deepwater port in the Netherlands. The Vessel, named the Bibby Resolution, belonged to a well-established Liverpool shipping line, one whose founder had invested in the Atlantic slave trade two hundred years before. But while the company that owned it had a history that went back centuries, the ship itself was unmistakably a product of the late twentieth century. Nature seems to have played us for a fool in the past few decades. Much theoretical research in fundamental physics during this time has focused on the search ‘beyond’ our best theories: beyond the standard model of particle physics, beyond the general theory of relativity, beyond quantum theory. But an epochal sequence of experimental results has proved many such speculations unfounded, and confirmed physics that I learnt at school half a century ago. I think physicists are failing to heed the lessons — and that, in turn, is hindering progress in physics.

Nature seems to have played us for a fool in the past few decades. Much theoretical research in fundamental physics during this time has focused on the search ‘beyond’ our best theories: beyond the standard model of particle physics, beyond the general theory of relativity, beyond quantum theory. But an epochal sequence of experimental results has proved many such speculations unfounded, and confirmed physics that I learnt at school half a century ago. I think physicists are failing to heed the lessons — and that, in turn, is hindering progress in physics. Established in 2000 — when Melinda French Gates was just 35 and Bill Gates was 44 and the world’s richest man — the foundation quickly became one of the most consequential philanthropies the world has ever seen, utterly reshaping the landscape of global public health, pouring more than $100 billion into causes starved for resources and helping save tens of millions of lives.

Established in 2000 — when Melinda French Gates was just 35 and Bill Gates was 44 and the world’s richest man — the foundation quickly became one of the most consequential philanthropies the world has ever seen, utterly reshaping the landscape of global public health, pouring more than $100 billion into causes starved for resources and helping save tens of millions of lives. Poets tend not to enjoy parties. W H Auden recalled that when T S Eliot was asked at a party if he was having fun, he replied, ‘Yes, if you see the essential horror of it all.’ ‘My wife and I have asked a crowd of craps/To come and waste their time and ours,’ writes Warlock-Williams in Philip Larkin’s ‘Vers de Société’. ‘Perhaps/You’d care to join us?’ ‘In a pig’s arse, friend,’ the speaker thinks. Why waste an evening holding a glass of ‘washing sherry’, catching ‘the drivel of some bitch/Who’s read nothing but Which’ and ‘Asking that ass about his fool research’? Small talk is usually the problem. Auden, in ‘At the Party’, moans how ‘Unrhymed, unrhythmical, the chatter goes:/Yet no one hears his own remarks as prose.’

Poets tend not to enjoy parties. W H Auden recalled that when T S Eliot was asked at a party if he was having fun, he replied, ‘Yes, if you see the essential horror of it all.’ ‘My wife and I have asked a crowd of craps/To come and waste their time and ours,’ writes Warlock-Williams in Philip Larkin’s ‘Vers de Société’. ‘Perhaps/You’d care to join us?’ ‘In a pig’s arse, friend,’ the speaker thinks. Why waste an evening holding a glass of ‘washing sherry’, catching ‘the drivel of some bitch/Who’s read nothing but Which’ and ‘Asking that ass about his fool research’? Small talk is usually the problem. Auden, in ‘At the Party’, moans how ‘Unrhymed, unrhythmical, the chatter goes:/Yet no one hears his own remarks as prose.’ In a presentation at the

In a presentation at the  There have always been many ways of dying badly. In the late eighteenth century, the devout English writer Samuel Johnson struggled furiously and profanely against his own demise, ordering his surgeon, beyond all hope and reason, to delve deeper with a scalpel to force more senseless bleeding. That was then. Surely things are better now? Not according to theologian and ethicist Travis Pickell, who argues in his new book that the vast array of modern end-of-life technologies have only ended up providing us with even more ways of shuffling off this mortal coil. What Pickell calls “burdened agency” is a particularly modern condition arising from a combination of two factors. First, because we are presented with more choices than ever before, we are obliged to choose more than ever before. Only a century ago, for example, an ailing person simply met death when it came. Now the ailing person must choose whether to undergo exceedingly invasive medical operations, or perhaps hasten death through physician-assisted suicide. Even if one were to reject both of these routes, that itself is a choice with consequences and moral meanings. Where once an elderly person dwindling slowly to death may have stood as an example of resolution and quiet dignity unto the last, now that person is stubbornly choosing to drain the healthcare coffers and drive up insurance premiums for the rest of us, when they could instead have disqualified themselves from life and saved society the burden.

There have always been many ways of dying badly. In the late eighteenth century, the devout English writer Samuel Johnson struggled furiously and profanely against his own demise, ordering his surgeon, beyond all hope and reason, to delve deeper with a scalpel to force more senseless bleeding. That was then. Surely things are better now? Not according to theologian and ethicist Travis Pickell, who argues in his new book that the vast array of modern end-of-life technologies have only ended up providing us with even more ways of shuffling off this mortal coil. What Pickell calls “burdened agency” is a particularly modern condition arising from a combination of two factors. First, because we are presented with more choices than ever before, we are obliged to choose more than ever before. Only a century ago, for example, an ailing person simply met death when it came. Now the ailing person must choose whether to undergo exceedingly invasive medical operations, or perhaps hasten death through physician-assisted suicide. Even if one were to reject both of these routes, that itself is a choice with consequences and moral meanings. Where once an elderly person dwindling slowly to death may have stood as an example of resolution and quiet dignity unto the last, now that person is stubbornly choosing to drain the healthcare coffers and drive up insurance premiums for the rest of us, when they could instead have disqualified themselves from life and saved society the burden. Trash is the hidden foundation of modern civilization. The ancient Trojans waded “ankle deep” in pottery shards and animal bones and whatever else they threw on the floor until they got so fed up with the mess that they paved it over. Rome’s first underground sewer, the Cloaca Maxima, which used the city’s rivers to sweep away waste, was constructed in the third century BC. Writing over two centuries after its construction, Livy praised the Cloaca as a monument without match, and Pliny, writing about a hundred years after him in AD 77, called it the “most noteworthy achievement” of the Roman Empire, beating out the Colosseum and the Parthenon. At the time of its construction the Cloaca was an engineering spectacle, and it also became a symbol of Roman civic virtue. Sturdy infrastructures that served the people endured; flashy monuments to emperors did not. During floods, Pliny noted, “the street above, massive blocks of stone are dragged along, and yet the tunnels do not cave in.” Humbly concealed by walls and by continued elevations of the surface of the city through centuries of accumulated matter, its invisibility ensured its durability.

Trash is the hidden foundation of modern civilization. The ancient Trojans waded “ankle deep” in pottery shards and animal bones and whatever else they threw on the floor until they got so fed up with the mess that they paved it over. Rome’s first underground sewer, the Cloaca Maxima, which used the city’s rivers to sweep away waste, was constructed in the third century BC. Writing over two centuries after its construction, Livy praised the Cloaca as a monument without match, and Pliny, writing about a hundred years after him in AD 77, called it the “most noteworthy achievement” of the Roman Empire, beating out the Colosseum and the Parthenon. At the time of its construction the Cloaca was an engineering spectacle, and it also became a symbol of Roman civic virtue. Sturdy infrastructures that served the people endured; flashy monuments to emperors did not. During floods, Pliny noted, “the street above, massive blocks of stone are dragged along, and yet the tunnels do not cave in.” Humbly concealed by walls and by continued elevations of the surface of the city through centuries of accumulated matter, its invisibility ensured its durability. A

A Driverless trucks are officially running their first regular long-haul routes, making roundtrips between Dallas and Houston.

Driverless trucks are officially running their first regular long-haul routes, making roundtrips between Dallas and Houston.