Alice Hines in More intelligent Life:

Once upon a time, there was a man who thought love was a maths problem.

Once upon a time, there was a man who thought love was a maths problem.

“Love is a capricious spark, a miraculous whirlwind,” one of his blog posts began, sarcastically. “It is found by following ancient prophecies, embarking on dangerous quests…Something like that, who knows. Anyway, it sounds like finding a girlfriend was crazy hard before computers!” The man’s name was Jacob. He is currently 32 and works in finance, creating software that helps banks comply with regulations. He has dark curly hair and a beard, a left eyebrow that’s often raised and, in his own words, a “dad bod”. His self-deprecating streak is tempered by optimism. “Growth mindset” is one of his favourite phrases. As in “I’m still not bisexual, but, you know, growth mindset.” For most of his life Jacob dated only when he’d received clear signs of encouragement from one of the many women he found beautiful or fascinating. In 2013 he moved to New York from North Carolina. Thanks to the volume of people using dating apps, it was suddenly possible to spend each night of the week with a different woman who was already intrigued by his online persona. There was the cheesemaker. The fashion designer. Three different med-school students. Jacob liked them all. On each date, he holidayed in another person’s world and learned something new.

But cumulatively, the experience was overwhelming. Jacob knew he wanted to get serious with someone, but he found it hard to weigh the merits of each of these potential partners against each other. So he did what he knew best: he made a spreadsheet. He called it “How to Choose a Goddess”. When he described this to me, some of the calculations lay beyond my comprehension. But my more quantitatively minded friends seemed impressed when I rattled them off.

More here.

Michael Tomasky in the NYRB:

Michael Tomasky in the NYRB: Anthony Paletta in The Boston Review:

Anthony Paletta in The Boston Review: Jeremy Rossman in The Conversation:

Jeremy Rossman in The Conversation: Greg Valliere of AGF Investments over at the firms’ website:

Greg Valliere of AGF Investments over at the firms’ website:

Fifty years ago, the screenwriter Robert Towne said to his girlfriend, “I want to write a movie for Jack.” He meant Nicholson — in those days, and possibly even now, there is only one Jack — who had just had his breakout role in “Easy Rider.” “A detective movie,” Towne explained. “Maybe Jane Fonda for the blonde.” He knew he wanted to set it in Los Angeles before the war, like a Raymond Chandler novel. But that was about the extent of it. When he told Nicholson, the actor naturally asked, “What’s it about?”

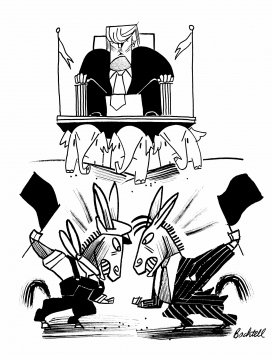

Fifty years ago, the screenwriter Robert Towne said to his girlfriend, “I want to write a movie for Jack.” He meant Nicholson — in those days, and possibly even now, there is only one Jack — who had just had his breakout role in “Easy Rider.” “A detective movie,” Towne explained. “Maybe Jane Fonda for the blonde.” He knew he wanted to set it in Los Angeles before the war, like a Raymond Chandler novel. But that was about the extent of it. When he told Nicholson, the actor naturally asked, “What’s it about?” What we are seeing right now is the collapse of civic authority and public trust at what is only the beginning of a protracted crisis. In the face of an onrushing pandemic, the United States has exhibited a near-total evacuation of responsibility and political leadership — a sociopathic disinterest in performing the basic function of government, which is to protect its citizens.

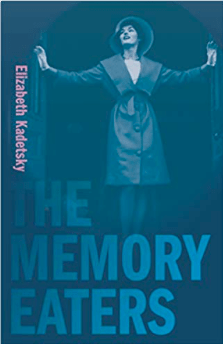

What we are seeing right now is the collapse of civic authority and public trust at what is only the beginning of a protracted crisis. In the face of an onrushing pandemic, the United States has exhibited a near-total evacuation of responsibility and political leadership — a sociopathic disinterest in performing the basic function of government, which is to protect its citizens. The Memory Eaters is told in the context of 1970s and 1980s New York City. The memoir moves from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post- traumatic stress disorder. The Memory Eaters is about consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia. More can be found at

The Memory Eaters is told in the context of 1970s and 1980s New York City. The memoir moves from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post- traumatic stress disorder. The Memory Eaters is about consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia. More can be found at  Elizabeth Kadetsky: Coming of age in the 1970s, I was exposed, through my mother, to a lot of what you might call groovy spirituality that enshrined this idea that you would find truth if you just relaxed your brain enough to let it come to you. This was the thinking behind the versions of so many of the trendy ideologies that we adopted: I Ching, astrology, Ouija Board, palm reading. I don’t think that we believed in the magic of any of these systems in the least. The idea was that these were all tools that helped you get more in tune with your subconscious. So, my mother’s ideas about “watching” definitely came out of that, that there was a sort of divine intelligence that you could tap into through paying close attention in both dream and waking life. It’s funny because when I think about it now I see the pitfalls of this mindset, especially for the writer.

Elizabeth Kadetsky: Coming of age in the 1970s, I was exposed, through my mother, to a lot of what you might call groovy spirituality that enshrined this idea that you would find truth if you just relaxed your brain enough to let it come to you. This was the thinking behind the versions of so many of the trendy ideologies that we adopted: I Ching, astrology, Ouija Board, palm reading. I don’t think that we believed in the magic of any of these systems in the least. The idea was that these were all tools that helped you get more in tune with your subconscious. So, my mother’s ideas about “watching” definitely came out of that, that there was a sort of divine intelligence that you could tap into through paying close attention in both dream and waking life. It’s funny because when I think about it now I see the pitfalls of this mindset, especially for the writer. Japan is reporting its first case of a person becoming reinfected with the coronavirus after showing signs they had fully recovered,

Japan is reporting its first case of a person becoming reinfected with the coronavirus after showing signs they had fully recovered,  Across the globe, a

Across the globe, a  This year’s report showed that

This year’s report showed that  Probably this is not the end of the world. But a plague is creeping around the globe at a seemingly exponential rate, killing some of us and affecting all of us. And this pandemic is only the most recent and most sudden of a series of afflictions facing humanity. We are rapidly replacing our natural habitat with one that is, on the one hand, made by human beings, and, on the other, proving difficult for us to manage—a situation we euphemistically refer to as “climate change.” On the political front, the past decade has seen a rise in civil unrest worldwide, and the leaders of a number of countries have given us reason to be less optimistic than we used to be about the prospects for global democracy. Given the ever-cheapening technology, weapons—including those of mass destruction—must be proliferating unnoticed. And all of the above is happening against a backdrop of low economic growth and stagnant wages, at least for most of the world’s wealthiest countries.

Probably this is not the end of the world. But a plague is creeping around the globe at a seemingly exponential rate, killing some of us and affecting all of us. And this pandemic is only the most recent and most sudden of a series of afflictions facing humanity. We are rapidly replacing our natural habitat with one that is, on the one hand, made by human beings, and, on the other, proving difficult for us to manage—a situation we euphemistically refer to as “climate change.” On the political front, the past decade has seen a rise in civil unrest worldwide, and the leaders of a number of countries have given us reason to be less optimistic than we used to be about the prospects for global democracy. Given the ever-cheapening technology, weapons—including those of mass destruction—must be proliferating unnoticed. And all of the above is happening against a backdrop of low economic growth and stagnant wages, at least for most of the world’s wealthiest countries.