Scott Koenig in Nautilus:

During the Spanish flu of 1918, it was Vick’s VapoRub. During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, it was canned food. Now, as the number of cases of COVID-19 grows worldwide, it’s, among other things, toilet paper. In times of precarity, people often resort to hoarding resources they think are likely to become scarce—panic buying, as it’s sometimes called. And while it’s easy to dismiss as an overreaction, it underscores just how difficult it can be, for both the general public and public health authorities, to choose the right response to a dangerous, rapidly evolving situation.

During the Spanish flu of 1918, it was Vick’s VapoRub. During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, it was canned food. Now, as the number of cases of COVID-19 grows worldwide, it’s, among other things, toilet paper. In times of precarity, people often resort to hoarding resources they think are likely to become scarce—panic buying, as it’s sometimes called. And while it’s easy to dismiss as an overreaction, it underscores just how difficult it can be, for both the general public and public health authorities, to choose the right response to a dangerous, rapidly evolving situation.

“One of the reasons we have so many challenges is that there’s just so much uncertainty, especially in the early days of an outbreak,” said Glen Nowak, a former director of media relations and communications at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), now a professor of advertising at the University of Georgia. Even for authorities, Nowak said, the number of moving parts and open questions during a public health crisis—where the disease originated, how infectious and deadly it is, how many people are already infected and who’s at risk—can be overwhelming. This means that the rest of us, despite the experts’ best efforts at communicating, often have to make do with limited and possibly even conflicting information. “What people are often thinking of, from a psychological standpoint, is ‘What is the best way for me to cope with this uncertainty?’” Nowak told me. For many people, coping may take the form of hoarding supplies in an attempt to assert control over the situation. Or it might mean looking to others for guidance—and if everyone else in your community is taking all the toilet paper, are you going to be the odd one out?

More here.

I

I One of English’s great, scornful, scorching political poems was premiered in an unassuming place: the postscript of a letter: “What a state England is in! But you will never write politics.” It was December 1819, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, then 27, was writing another pushily impassioned letter to Leigh Hunt, a poet, a radical, and the founding editor of the Examiner. Since 1818, Shelley and his wife, the novelist Mary Shelley, had been restless expatriates in Italy, never in any one city for long. Dead by drowning three years later, he never revisited his home country and never quite escaped its orbit, gravitationally tugged back by England’s tumultuous politics. However desperate for Hunt’s dispatches (“Why don’t you write to us?” the letter opens), Shelley, never afraid to speak his mind, thought his friend deserved a “scolding”: “I wish, then, that you would write a paper in the Examiner, on the actual state of the country, and what, under all the circumstances of the conflicting passions and interests of men, we are to expect.” Surely Shelley meant wish wholeheartedly, but he was also setting up Hunt for a surprise present, which he introduced, with coy calm, in his postscript. “I send you a sonnet. I do not expect you to publish it, but you may show it to whom you please.”

One of English’s great, scornful, scorching political poems was premiered in an unassuming place: the postscript of a letter: “What a state England is in! But you will never write politics.” It was December 1819, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, then 27, was writing another pushily impassioned letter to Leigh Hunt, a poet, a radical, and the founding editor of the Examiner. Since 1818, Shelley and his wife, the novelist Mary Shelley, had been restless expatriates in Italy, never in any one city for long. Dead by drowning three years later, he never revisited his home country and never quite escaped its orbit, gravitationally tugged back by England’s tumultuous politics. However desperate for Hunt’s dispatches (“Why don’t you write to us?” the letter opens), Shelley, never afraid to speak his mind, thought his friend deserved a “scolding”: “I wish, then, that you would write a paper in the Examiner, on the actual state of the country, and what, under all the circumstances of the conflicting passions and interests of men, we are to expect.” Surely Shelley meant wish wholeheartedly, but he was also setting up Hunt for a surprise present, which he introduced, with coy calm, in his postscript. “I send you a sonnet. I do not expect you to publish it, but you may show it to whom you please.” On screen and off, Edwards came to see something in Andrews that Kael—and other critics like her—could not. Underneath her wimple, as the nuns say of Maria, Andrews had curlers in her hair. Yes, in nearly every role she comports herself like the queen of some imaginary, borderless kingdom. But there is also an odd tension beneath the surface of Andrews’s most ostensibly wholesome performances—the kind that can drive a viewer to all sorts of wild speculation about what Mary Poppins gets up to on her days off, and that can inspire an entire volume of queer theory that hinges upon a dissident reading of the boyish Maria von Trapp (see: Stacy Wolf’s 2002 A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical). Pinning down the hidden complexities and contradictions of Andrews’s stardom is a bit like holding a moonbeam in your hand. As composer and broadcaster Neil Brand put it to The Guardian last year, Andrews may just be “the politest rebel in all cinema.”

On screen and off, Edwards came to see something in Andrews that Kael—and other critics like her—could not. Underneath her wimple, as the nuns say of Maria, Andrews had curlers in her hair. Yes, in nearly every role she comports herself like the queen of some imaginary, borderless kingdom. But there is also an odd tension beneath the surface of Andrews’s most ostensibly wholesome performances—the kind that can drive a viewer to all sorts of wild speculation about what Mary Poppins gets up to on her days off, and that can inspire an entire volume of queer theory that hinges upon a dissident reading of the boyish Maria von Trapp (see: Stacy Wolf’s 2002 A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical). Pinning down the hidden complexities and contradictions of Andrews’s stardom is a bit like holding a moonbeam in your hand. As composer and broadcaster Neil Brand put it to The Guardian last year, Andrews may just be “the politest rebel in all cinema.” ‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse, told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family.

‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse, told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family. Why is consciousness so perplexing to so many? Perhaps, owing to our being conscious, we regard ourselves as experts on the matter, and it seems to us blindingly obvious that consciousness could not possibly be a brain state or process. We have a front-row seat, an unmediated first-hand awareness of what conscious experiences are like, and we know well-enough what brain processes are like. The two could not be more different. In the hands of philosophers, this sentiment is transmuted into the doctrine that consciousness cannot be identified with, or ‘reduced to’, anything physical. The reduction in question must be a relation among explanations, or predicates, not as it is sometimes cast, a relation among properties. What would it be to reduce something to something else? If the As are not reducible to the Bs, explanations of the As could not be derived from explanations of the Bs, nor could A-terms be analysed or paraphrased in a B-vocabulary.

Why is consciousness so perplexing to so many? Perhaps, owing to our being conscious, we regard ourselves as experts on the matter, and it seems to us blindingly obvious that consciousness could not possibly be a brain state or process. We have a front-row seat, an unmediated first-hand awareness of what conscious experiences are like, and we know well-enough what brain processes are like. The two could not be more different. In the hands of philosophers, this sentiment is transmuted into the doctrine that consciousness cannot be identified with, or ‘reduced to’, anything physical. The reduction in question must be a relation among explanations, or predicates, not as it is sometimes cast, a relation among properties. What would it be to reduce something to something else? If the As are not reducible to the Bs, explanations of the As could not be derived from explanations of the Bs, nor could A-terms be analysed or paraphrased in a B-vocabulary. This is a special episode of Mindscape, thrown together quickly. Many thanks to Tara Smith for joining me on short notice. Tara is an epidemiologist, and a great person to talk to about the novel coronavirus (and its associated disease, COVID-19) pandemic currently threatening the world. We talk about what viruses are, how they spread, and a lot of the science behind virology and pandemics. We also take a practical turn, talking about what measures (washing hands, social distancing, self-isolation) are useful at combating the spread of the virus, and which (wearing masks) are probably not. Then we look to the future, to ask what the endgame here is; Tara suggests that the kind of drastic measure we are currently putting up with might last a long time indeed.

This is a special episode of Mindscape, thrown together quickly. Many thanks to Tara Smith for joining me on short notice. Tara is an epidemiologist, and a great person to talk to about the novel coronavirus (and its associated disease, COVID-19) pandemic currently threatening the world. We talk about what viruses are, how they spread, and a lot of the science behind virology and pandemics. We also take a practical turn, talking about what measures (washing hands, social distancing, self-isolation) are useful at combating the spread of the virus, and which (wearing masks) are probably not. Then we look to the future, to ask what the endgame here is; Tara suggests that the kind of drastic measure we are currently putting up with might last a long time indeed.

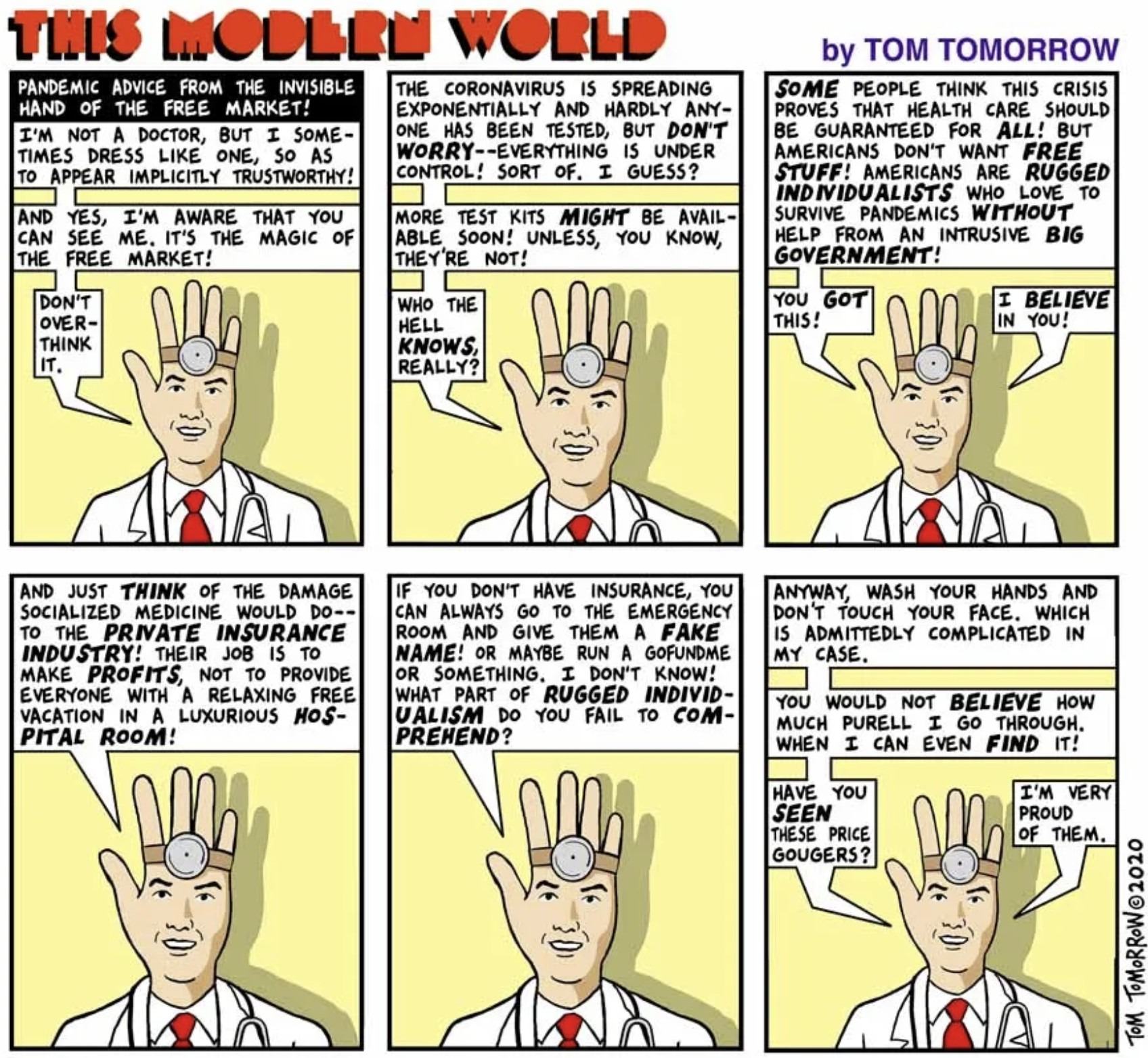

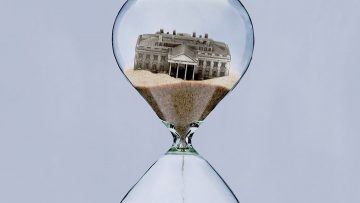

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19—the acute respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—a

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19—the acute respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—a  One of the best-known sketches from Monty Python’s Flying Circus features John Cleese as a bowler-hatted bureaucrat with the fictional

One of the best-known sketches from Monty Python’s Flying Circus features John Cleese as a bowler-hatted bureaucrat with the fictional  Usually a question like this is theoretical: What would it be like to find your town, your state, your country, shut off from the rest of the world, its citizens confined to their homes, as a contagion spreads, infecting thousands, and subjecting thousands more to quarantine? How would you cope if an epidemic disrupted daily life, closing schools, packing hospitals, and putting social gatherings, sporting events and concerts, conferences, festivals and travel plans on indefinite hold?

Usually a question like this is theoretical: What would it be like to find your town, your state, your country, shut off from the rest of the world, its citizens confined to their homes, as a contagion spreads, infecting thousands, and subjecting thousands more to quarantine? How would you cope if an epidemic disrupted daily life, closing schools, packing hospitals, and putting social gatherings, sporting events and concerts, conferences, festivals and travel plans on indefinite hold? The words social distancing have already defined 2020, and everyone is already tired of them (and

The words social distancing have already defined 2020, and everyone is already tired of them (and  O

O