David Cyranoski in Nature:

As the new coronavirus marches around the globe, countries with escalating outbreaks are eager to learn whether China’s extreme lockdowns were responsible for bringing the crisis there under control. Other nations are now following China’s lead and limiting movement within their borders, while dozens of countries have restricted international visitors. In mid-January, Chinese authorities introduced unprecedented measures to contain the virus, stopping movement in and out of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and 15 other cities in Hubei province — home to more than 60 million people. Flights and trains were suspended, and roads were blocked. Soon after, people in many Chinese cities were told to stay home and venture out only to get food or medical help. Some 760 million people, roughly half the country’s population, were confined to their homes, according to the New York Times. It’s now two months since the lockdowns began — some of which are still in place — and the number of new cases there is around a couple dozen per day, down from thousands per day at the peak. “These extreme limitations on population movement have been quite successful,” says Michael Osterholm, an infectious-disease scientist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

As the new coronavirus marches around the globe, countries with escalating outbreaks are eager to learn whether China’s extreme lockdowns were responsible for bringing the crisis there under control. Other nations are now following China’s lead and limiting movement within their borders, while dozens of countries have restricted international visitors. In mid-January, Chinese authorities introduced unprecedented measures to contain the virus, stopping movement in and out of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and 15 other cities in Hubei province — home to more than 60 million people. Flights and trains were suspended, and roads were blocked. Soon after, people in many Chinese cities were told to stay home and venture out only to get food or medical help. Some 760 million people, roughly half the country’s population, were confined to their homes, according to the New York Times. It’s now two months since the lockdowns began — some of which are still in place — and the number of new cases there is around a couple dozen per day, down from thousands per day at the peak. “These extreme limitations on population movement have been quite successful,” says Michael Osterholm, an infectious-disease scientist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

In a report released late last month, the World Health Organization congratulated China on a “unique and unprecedented public health response [that] reversed the escalating cases”. But the crucial question is which interventions in China were the most important in driving down the spread of the virus, says Gabriel Leung, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of Hong Kong. “The countries now facing their first wave [of infections] need to know this,” he says.

More here.

To understand why the world economy is in grave peril because of the spread of coronavirus, it helps to grasp one idea that is at once blindingly obvious and sneakily profound.

To understand why the world economy is in grave peril because of the spread of coronavirus, it helps to grasp one idea that is at once blindingly obvious and sneakily profound. “What good is half a wing?” That’s the rhetorical question often asked by people who have trouble accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Of course it’s a very answerable question, but figuring out what exactly the answer is leads us to some fascinating biology. Neil Shubin should know: he is the co-discoverer of

“What good is half a wing?” That’s the rhetorical question often asked by people who have trouble accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Of course it’s a very answerable question, but figuring out what exactly the answer is leads us to some fascinating biology. Neil Shubin should know: he is the co-discoverer of  I have never been much of a runner, but on Saturday I find myself suiting up for exercise and meeting a friend for a run. It has been a week since the Italian prime minister

I have never been much of a runner, but on Saturday I find myself suiting up for exercise and meeting a friend for a run. It has been a week since the Italian prime minister  The Belgrade installation of Sound Corridor missed an opportunity to connect Abramović’s work to that of her contemporaries. But it was nevertheless a startling introduction to an exhibition with a haunting soundscape, evocative of melancholy, death, and nostalgic enchantment. Moving from the corridor of recorded gunfire into the lobby, one could hear Abramović’s screams from the video Freeing the Voice (1975) on the second floor. For that performance at the SKC, the artist lay on her back screaming for three hours, until she lost her voice. On the first floor, a large but quiet black-box installation featured video footage from The Artist Is Present (2010), the performance staged during her retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Opposite this installation stood Private Archaeology (1997–2015), a set of wooden cabinets holding a collection of sketches, collages, artifacts, and ephemera from Abramović’s archive, a deeply self-mythologizing installation that surprisingly did not include any reference to her SKC involvement. At the top of the stairs, large projections showed black-and-white footage of some of Abramović’s best-known works: Freeing the Voice, mentioned above; Freeing the Body (1976), in which she wrapped her head in a black scarf and danced for eight hours, until she collapsed; and several of her performances made in collaboration with German artist Ulay, including one where they slam their bodies together, and another where they sit opposite each other and scream.

The Belgrade installation of Sound Corridor missed an opportunity to connect Abramović’s work to that of her contemporaries. But it was nevertheless a startling introduction to an exhibition with a haunting soundscape, evocative of melancholy, death, and nostalgic enchantment. Moving from the corridor of recorded gunfire into the lobby, one could hear Abramović’s screams from the video Freeing the Voice (1975) on the second floor. For that performance at the SKC, the artist lay on her back screaming for three hours, until she lost her voice. On the first floor, a large but quiet black-box installation featured video footage from The Artist Is Present (2010), the performance staged during her retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Opposite this installation stood Private Archaeology (1997–2015), a set of wooden cabinets holding a collection of sketches, collages, artifacts, and ephemera from Abramović’s archive, a deeply self-mythologizing installation that surprisingly did not include any reference to her SKC involvement. At the top of the stairs, large projections showed black-and-white footage of some of Abramović’s best-known works: Freeing the Voice, mentioned above; Freeing the Body (1976), in which she wrapped her head in a black scarf and danced for eight hours, until she collapsed; and several of her performances made in collaboration with German artist Ulay, including one where they slam their bodies together, and another where they sit opposite each other and scream. During World War I, when soldiers thought longingly of home, their minds often turned to the garden. Indeed, they made small gardens in the trenches, planting bulbs in empty brass shell-casings. In a catalog essay, the Garden Museum’s director, Christopher Woodward, quotes Ford Madox-Ford’s No Enemy: A Tale of Reconstruction (1929), on the soldier’s dream of return, not to a landscape but “a nook rather,” at the end of a valley “with a little stream, just a trickle level with the grass of the bottom. You understand the idea—a sanctuary.” So the focus of the show is not on great estates but on domestic landscapes and individual plants, and implicitly on the garden’s allegorical power: the myths of Eden.

During World War I, when soldiers thought longingly of home, their minds often turned to the garden. Indeed, they made small gardens in the trenches, planting bulbs in empty brass shell-casings. In a catalog essay, the Garden Museum’s director, Christopher Woodward, quotes Ford Madox-Ford’s No Enemy: A Tale of Reconstruction (1929), on the soldier’s dream of return, not to a landscape but “a nook rather,” at the end of a valley “with a little stream, just a trickle level with the grass of the bottom. You understand the idea—a sanctuary.” So the focus of the show is not on great estates but on domestic landscapes and individual plants, and implicitly on the garden’s allegorical power: the myths of Eden. When Stone mustered out of the navy in the late fifties, the United States had perhaps reached its zenith in terms of economic success and dominance, political hegemony worldwide, and a vibrant and vigorous culture, ripe for exportation in multiple embodiments: from serious literature and high art to B movies, pop music, and Coca-Cola. It seemed a national moment free of self-doubt—although a considerable dysphoria would soon begin to express itself, as the social upheavals of the sixties began. Stone, who did not begin the world from a position of privilege, was quicker than most to see the shadows cast by the rising American star. In his work, he would repeatedly portray those bright aspirations set off by a surrounding darkness that was likely in the end to devour them.

When Stone mustered out of the navy in the late fifties, the United States had perhaps reached its zenith in terms of economic success and dominance, political hegemony worldwide, and a vibrant and vigorous culture, ripe for exportation in multiple embodiments: from serious literature and high art to B movies, pop music, and Coca-Cola. It seemed a national moment free of self-doubt—although a considerable dysphoria would soon begin to express itself, as the social upheavals of the sixties began. Stone, who did not begin the world from a position of privilege, was quicker than most to see the shadows cast by the rising American star. In his work, he would repeatedly portray those bright aspirations set off by a surrounding darkness that was likely in the end to devour them. The term “bird’s nest” has come to describe a messy hairdo, tangled fishing line and other unspeakably knotty conundrums. But that does birds an injustice. Their tiny brains, dense with neurons, produce marvels that have long captured scientific interest as naturally selected engineering solutions — yet nests are still not well understood. One effort to disentangle the structural dynamics of the nest is underway in the sunny yellow lab — the Mechanical Biomimetics and Open Design Lab — of Hunter King, an experimental soft-matter physicist at the University of Akron in Ohio. “We hypothesize that a bird nest might effectively be a disordered stick bomb, with just enough stored energy to keep it rigid,” Dr. King said. He is the principal investigator of an ongoing study, with

The term “bird’s nest” has come to describe a messy hairdo, tangled fishing line and other unspeakably knotty conundrums. But that does birds an injustice. Their tiny brains, dense with neurons, produce marvels that have long captured scientific interest as naturally selected engineering solutions — yet nests are still not well understood. One effort to disentangle the structural dynamics of the nest is underway in the sunny yellow lab — the Mechanical Biomimetics and Open Design Lab — of Hunter King, an experimental soft-matter physicist at the University of Akron in Ohio. “We hypothesize that a bird nest might effectively be a disordered stick bomb, with just enough stored energy to keep it rigid,” Dr. King said. He is the principal investigator of an ongoing study, with

Less than a century after the Black Death descended into Europe and killed 75 million people—as much as 60 percent of the population (90% in some places) dead in the five years after 1347—an anonymous Alsatian engraver with the fantastic appellation of “Master of the Playing Cards” saw fit to depict St. Sebastian: the patron saint of plague victims. Making his name, literally, from the series of playing cards he produced at the moment when the pastime first became popular in Germany, the engraver decorated his suits with bears and wolves, lions and birds, flowers and woodwoses. The Master of Playing Cards’s largest engraving, however, was the aforementioned depiction of the unfortunate third-century martyr who suffered by order of the Emperor Diocletian. A violent image, but even several generations after the worst of the Black Death, and Sebastian still resonated with the populace, who remembered that “To many Europeans, the pestilence seemed to be the punishment of a wrathful Creator,” as John Kelly notes in

Less than a century after the Black Death descended into Europe and killed 75 million people—as much as 60 percent of the population (90% in some places) dead in the five years after 1347—an anonymous Alsatian engraver with the fantastic appellation of “Master of the Playing Cards” saw fit to depict St. Sebastian: the patron saint of plague victims. Making his name, literally, from the series of playing cards he produced at the moment when the pastime first became popular in Germany, the engraver decorated his suits with bears and wolves, lions and birds, flowers and woodwoses. The Master of Playing Cards’s largest engraving, however, was the aforementioned depiction of the unfortunate third-century martyr who suffered by order of the Emperor Diocletian. A violent image, but even several generations after the worst of the Black Death, and Sebastian still resonated with the populace, who remembered that “To many Europeans, the pestilence seemed to be the punishment of a wrathful Creator,” as John Kelly notes in  Wuhan is known colloquially as one of the “four furnaces” (四大火炉) of China for its oppressively hot humid summer, shared with Chongqing, Nanjing and alternately Nanchang or Changsha, all bustling cities with long histories along or near the Yangtze river valley. Of the four, Wuhan, however, is also sprinkled with literal furnaces: the massive urban complex acts as a sort of nucleus for the steel, concrete and other construction-related industries of China, its landscape dotted with the slowly-cooling blast furnaces of the remnant state-owned iron and steel foundries, now plagued by

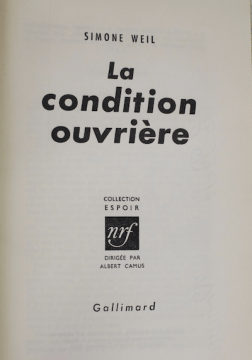

Wuhan is known colloquially as one of the “four furnaces” (四大火炉) of China for its oppressively hot humid summer, shared with Chongqing, Nanjing and alternately Nanchang or Changsha, all bustling cities with long histories along or near the Yangtze river valley. Of the four, Wuhan, however, is also sprinkled with literal furnaces: the massive urban complex acts as a sort of nucleus for the steel, concrete and other construction-related industries of China, its landscape dotted with the slowly-cooling blast furnaces of the remnant state-owned iron and steel foundries, now plagued by  IN THE SUMMER or fall of 1943, La France libre, the London-based provisional government led by General Charles de Gaulle, received a letter from across the Channel. In three closely typed pages, the writer, identifying himself as “un résistant intellectuel,” described the “anguish” he felt as he surveyed the political and moral landscape of Nazi-occupied France. We are teetering, he declared, between renaissance and ruin. Moreover, those struggling on behalf of the former were driven by two often competing ideals: “The clear desire for justice and profound demand for liberty.” Yet, he warned, if we can one day create a doctrine based on these two imperatives, they would lead to the “complete overhaul” of the nation’s constitutional and financial institutions. One way or another, in short, France would never again be the same.

IN THE SUMMER or fall of 1943, La France libre, the London-based provisional government led by General Charles de Gaulle, received a letter from across the Channel. In three closely typed pages, the writer, identifying himself as “un résistant intellectuel,” described the “anguish” he felt as he surveyed the political and moral landscape of Nazi-occupied France. We are teetering, he declared, between renaissance and ruin. Moreover, those struggling on behalf of the former were driven by two often competing ideals: “The clear desire for justice and profound demand for liberty.” Yet, he warned, if we can one day create a doctrine based on these two imperatives, they would lead to the “complete overhaul” of the nation’s constitutional and financial institutions. One way or another, in short, France would never again be the same.