Maria Farrell in The Conversationalist:

Maria Farrell in The Conversationalist:

A few months ago, I was contacted by a senior executive who was about to leave a marketing firm. He got in touch because I’ve worked on the non-profit side of tech for a long time, with lots of volunteering on digital and human rights. He wanted to ‘give back’. Could I put him in touch with digital rights activists? Sure. We met for coffee and I made some introductions. It was a perfectly lovely interaction with a perfectly lovely man. Perhaps he will do some good, sharing his expertise with the people working to save democracy and our private lives from the surveillance capitalism machine of his former employers. The way I rationalized helping him was: firstly, it’s nice to be nice; and secondly, movements are made of people who start off far apart but converge on a destination. And isn’t it an unqualified good when an insider decides to do the right thing, however late?

The Prodigal Son is a New Testament parable about two sons. One stays home to work the farm. The other cashes in his inheritance and gambles it away. When the gambler comes home, his father slaughters the fattened calf to celebrate, leaving the virtuous, hard-working brother to complain that all these years he wasn’t even given a small goat to share with his friends. His father replies that the prodigal son ‘was dead, now he’s alive; lost, now he’s found’. Cue party streamers. It’s a touching story of redemption, with a massive payload of moral hazard. It’s about coming home, saying sorry, being joyfully forgiven and starting again. Most of us would love to star in it, but few of us will be given the chance.

More here.

Samanth Subramanian in the New Yorker:

Samanth Subramanian in the New Yorker:

The brain is wider than the sky,

The brain is wider than the sky, In the 2017 film Star Wars: The Last Jedi, the character Finn plans to sacrifice himself for the rebel cause by flying into the glowing-hot core of a giant weapon trained on the rebel hideout. As his rickety vessel speeds toward the target, he is sideswiped off his path by another rebel, Rose. When Finn asks Rose why she prevented his self- sacrifice, she replies: “That’s not how we’re going to win. Not fighting what we hate, [but] saving what we love.” It is difficult to imagine such a scene appearing in earlier Star Wars episodes.

In the 2017 film Star Wars: The Last Jedi, the character Finn plans to sacrifice himself for the rebel cause by flying into the glowing-hot core of a giant weapon trained on the rebel hideout. As his rickety vessel speeds toward the target, he is sideswiped off his path by another rebel, Rose. When Finn asks Rose why she prevented his self- sacrifice, she replies: “That’s not how we’re going to win. Not fighting what we hate, [but] saving what we love.” It is difficult to imagine such a scene appearing in earlier Star Wars episodes. The huge success of the Netflix teen drama series, Sex Education, is partly fuelled by the poor quality of sex ed lessons in schools. Young people are fed up with prudish, vague and incomplete information from their teachers – and parents. So they are turning to the often explicit TV series to get answers.

The huge success of the Netflix teen drama series, Sex Education, is partly fuelled by the poor quality of sex ed lessons in schools. Young people are fed up with prudish, vague and incomplete information from their teachers – and parents. So they are turning to the often explicit TV series to get answers. Las Vegas is a place about which people have ideas. They have thoughts and generalizations, takes and counter-takes, most of them detached from any genuine experience and uninformed by any concrete reality. This is true of many cities—New York, Paris, Prague in the 1990s—owing to books and movies and tourism bureaus, but it is particularly true of Las Vegas. It is a place that looms large in popular culture as a setting for blowout parties and high-stakes gambling, a place where one might wed a stripper with a heart of gold, like Ed Helms does in The Hangover, or hole up in a hotel room and drink oneself to death, as Nicolas Cage does in Leaving Las Vegas. Even those who would never go to Las Vegas are in the grip of its mythology. Yet roughly half of all Americans, or around 165 million people, have visited and one slivery weekend glimpse bestows on them a sense of ownership and authority.

Las Vegas is a place about which people have ideas. They have thoughts and generalizations, takes and counter-takes, most of them detached from any genuine experience and uninformed by any concrete reality. This is true of many cities—New York, Paris, Prague in the 1990s—owing to books and movies and tourism bureaus, but it is particularly true of Las Vegas. It is a place that looms large in popular culture as a setting for blowout parties and high-stakes gambling, a place where one might wed a stripper with a heart of gold, like Ed Helms does in The Hangover, or hole up in a hotel room and drink oneself to death, as Nicolas Cage does in Leaving Las Vegas. Even those who would never go to Las Vegas are in the grip of its mythology. Yet roughly half of all Americans, or around 165 million people, have visited and one slivery weekend glimpse bestows on them a sense of ownership and authority. How do those of us who have enough to eat account for hunger? We often imagine it’s about drought, famine, lack of rain, corruption and incompetence. We need to be much more imaginative. Hunger is about land-grabbing, cartels, early marriage, immunisation, genetically modified crops, child development, slums, climate change, subsidies, chemical pollution, derivative markets, deforestation, child labour, food banks and much, much more. Systemic hunger is about the failure of our food systems and the fact that one half of the world is eating the food of the other half. This is not new. In the 19th century, Europe improved its food availability and quality by importing foodstuffs grown elsewhere.

How do those of us who have enough to eat account for hunger? We often imagine it’s about drought, famine, lack of rain, corruption and incompetence. We need to be much more imaginative. Hunger is about land-grabbing, cartels, early marriage, immunisation, genetically modified crops, child development, slums, climate change, subsidies, chemical pollution, derivative markets, deforestation, child labour, food banks and much, much more. Systemic hunger is about the failure of our food systems and the fact that one half of the world is eating the food of the other half. This is not new. In the 19th century, Europe improved its food availability and quality by importing foodstuffs grown elsewhere. The blur is as close as Mr. Richter has ever come to a stylistic signature, and it recurs here in seascapes, landscapes, and street scenes; portraits of his daughter Betty, her head resting on a table like meat on the butcher block, or his ex-wife, the artist

The blur is as close as Mr. Richter has ever come to a stylistic signature, and it recurs here in seascapes, landscapes, and street scenes; portraits of his daughter Betty, her head resting on a table like meat on the butcher block, or his ex-wife, the artist  Suppose that you’re interested in how false beliefs – ‘fake news’ – spread across a population. The problem is extraordinarily complicated. What people come to believe depends on a myriad of factors: which news outlets they read; who their friends and colleagues are; their ability to distinguish between fact and fiction; their social media echo chamber; and so on. A very good way of investigating a complicated phenomenon is to model it. This involves the construction of a simplified version of it and the investigation of the behaviour of that simplified version in order to draw conclusions about the actual system of interest. Both of these steps require a curious and playful outlook.

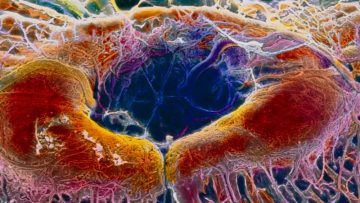

Suppose that you’re interested in how false beliefs – ‘fake news’ – spread across a population. The problem is extraordinarily complicated. What people come to believe depends on a myriad of factors: which news outlets they read; who their friends and colleagues are; their ability to distinguish between fact and fiction; their social media echo chamber; and so on. A very good way of investigating a complicated phenomenon is to model it. This involves the construction of a simplified version of it and the investigation of the behaviour of that simplified version in order to draw conclusions about the actual system of interest. Both of these steps require a curious and playful outlook. A person with a genetic condition that causes blindness has become the first to receive a CRISPR–Cas9 gene therapy administered directly into their body. The treatment is part of a landmark clinical trial to test the ability of CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing techniques to remove mutations that cause a rare condition called Leber’s congenital amaurosis 10 (LCA10). No treatment is currently available for the disease, which is a leading cause of blindness in childhood. For the latest trial, the components of the gene-editing system – encoded in the genome of a virus — are injected directly into the eye, near photoreceptor cells. By contrast, previous CRISPR–Cas9 clinical trials have used the technique to edit the genomes of cells that have been removed from the body. The material is then infused back into the patient. “It’s an exciting time,” says Mark Pennesi, a specialist in inherited retinal diseases at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Pennesi is collaborating with the pharmaceutical companies Editas Medicine of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Allergan of Dublin to conduct the trial, which has been named BRILLIANCE.

A person with a genetic condition that causes blindness has become the first to receive a CRISPR–Cas9 gene therapy administered directly into their body. The treatment is part of a landmark clinical trial to test the ability of CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing techniques to remove mutations that cause a rare condition called Leber’s congenital amaurosis 10 (LCA10). No treatment is currently available for the disease, which is a leading cause of blindness in childhood. For the latest trial, the components of the gene-editing system – encoded in the genome of a virus — are injected directly into the eye, near photoreceptor cells. By contrast, previous CRISPR–Cas9 clinical trials have used the technique to edit the genomes of cells that have been removed from the body. The material is then infused back into the patient. “It’s an exciting time,” says Mark Pennesi, a specialist in inherited retinal diseases at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Pennesi is collaborating with the pharmaceutical companies Editas Medicine of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Allergan of Dublin to conduct the trial, which has been named BRILLIANCE. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States was surprised and unprepared, but it was quickly freed of its illusions. The same does not hold true for the COVID-19 epidemic. The attack is underway and our defenses are down – but so far our illusions remain intact.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States was surprised and unprepared, but it was quickly freed of its illusions. The same does not hold true for the COVID-19 epidemic. The attack is underway and our defenses are down – but so far our illusions remain intact. I think I’m finally ready to come out as a

I think I’m finally ready to come out as a  Of all these correspondents, however, Albert Murray was the one who best drew out of Ellison both the literary lion and the streetwise sophisticate at his most unbuttoned and inventive. Murray was a couple years behind Ellison at Tuskegee and was teaching literature there when they began corresponding in 1950. While on the home stretch of Invisible Man, Ellison, feeling super-relaxed, concedes to Murray, as he could to no one else, that the book has become “just a big fat ole Negro lie, meant to be told during cotton picking time over a water bucket full of corn, with a dipper passing back and forth at a good fast clip so that no one, not even the narrator himself, will realize how utterly preposterous the lie actually is.” In Murray (a novelist and critic of comparable stature whose own side of the decade-long exchange can be found in 2000’s Trading Twelves), Ellison found a boon companion with whom he could comfortably revel in the foot-stomping, jump-dancing, blues-shouting verities of their shared cultural references and unfurl freewheeling inquiries into the literary masters (Hemingway, Malraux, and Faulkner, among others) who had nourished them since their respective youths.

Of all these correspondents, however, Albert Murray was the one who best drew out of Ellison both the literary lion and the streetwise sophisticate at his most unbuttoned and inventive. Murray was a couple years behind Ellison at Tuskegee and was teaching literature there when they began corresponding in 1950. While on the home stretch of Invisible Man, Ellison, feeling super-relaxed, concedes to Murray, as he could to no one else, that the book has become “just a big fat ole Negro lie, meant to be told during cotton picking time over a water bucket full of corn, with a dipper passing back and forth at a good fast clip so that no one, not even the narrator himself, will realize how utterly preposterous the lie actually is.” In Murray (a novelist and critic of comparable stature whose own side of the decade-long exchange can be found in 2000’s Trading Twelves), Ellison found a boon companion with whom he could comfortably revel in the foot-stomping, jump-dancing, blues-shouting verities of their shared cultural references and unfurl freewheeling inquiries into the literary masters (Hemingway, Malraux, and Faulkner, among others) who had nourished them since their respective youths. In mid-January, The New York Times

In mid-January, The New York Times  Setting aside these internecine disputes, after the very long durée of his historical exegesis, what is Piketty’s main thesis? It is that the sharp growth in inequality of income and, especially, wealth we have seen in most Western societies in recent years is unsustainable. Furthermore, our traditional political parties find it impossible to engage with the problem. Taking the UK as an example, he argues that the two main parties are now led by the ‘Brahmin Left’, with Labour having become the party of the highly educated, its working-class roots withered, and the ‘Merchant Right’, who cling to the belief that loosely regulated free markets will deliver prosperity for all, one day. He argues that the trickle-down theory on which that latter assumption is based has given way to a trickle-up phenomenon, with the rich getting richer and the incomes of the middling sort stagnating.

Setting aside these internecine disputes, after the very long durée of his historical exegesis, what is Piketty’s main thesis? It is that the sharp growth in inequality of income and, especially, wealth we have seen in most Western societies in recent years is unsustainable. Furthermore, our traditional political parties find it impossible to engage with the problem. Taking the UK as an example, he argues that the two main parties are now led by the ‘Brahmin Left’, with Labour having become the party of the highly educated, its working-class roots withered, and the ‘Merchant Right’, who cling to the belief that loosely regulated free markets will deliver prosperity for all, one day. He argues that the trickle-down theory on which that latter assumption is based has given way to a trickle-up phenomenon, with the rich getting richer and the incomes of the middling sort stagnating.