Emily LaBarge at Artforum:

Biography drags after Szapocznikow like a phantom limb, threatening to eclipse a practice as rooted in materiality and experiment as it is in the individual life experience of a body and mind. Born to a Jewish family in Kalisz, Poland, in 1926, she survived two ghettos and three concentration camps, as well as tuberculosis, before dying of breast cancer at age forty-six. Her work has frequently suffered from being interpreted too literally, theorized as representations of trauma or of psychic wounds. But every encounter I’ve had demands the opposite: The abstracted figuration Szapocznikow pursued in this later work, which hovers between the real body and its imagined or felt states, demands nuanced reading. We have the body truncated, unheroic, beguiling, as in her colored polyester resin lamps, mouths, and breasts lit from within—glowing sentinels pink, flesh colored, black, crimson. The body that grows where it shouldn’t, whose parts we cannot integrate, appears unnatural but unsettlingly erotic, tactile, as in two works titled Tumeur (Tumor), both made around 1970, consisting of lumpy mounds of resin and gauze, with ruby-red lips straining to the surface from within.

Biography drags after Szapocznikow like a phantom limb, threatening to eclipse a practice as rooted in materiality and experiment as it is in the individual life experience of a body and mind. Born to a Jewish family in Kalisz, Poland, in 1926, she survived two ghettos and three concentration camps, as well as tuberculosis, before dying of breast cancer at age forty-six. Her work has frequently suffered from being interpreted too literally, theorized as representations of trauma or of psychic wounds. But every encounter I’ve had demands the opposite: The abstracted figuration Szapocznikow pursued in this later work, which hovers between the real body and its imagined or felt states, demands nuanced reading. We have the body truncated, unheroic, beguiling, as in her colored polyester resin lamps, mouths, and breasts lit from within—glowing sentinels pink, flesh colored, black, crimson. The body that grows where it shouldn’t, whose parts we cannot integrate, appears unnatural but unsettlingly erotic, tactile, as in two works titled Tumeur (Tumor), both made around 1970, consisting of lumpy mounds of resin and gauze, with ruby-red lips straining to the surface from within.

more here.

They blew up the mausoleum—or tried to—during a live broadcast on Bulgarian national television on August 21, 1999. It was a hot and cloudless day in the capital city of Sofia, perfect weather for a demolition. Ten years after the collapse of the country’s Communist regime there was still unfinished business to take care of. The mausoleum’s one and only occupant, the mummy of Georgi Dimitrov, “the Great Leader and Teacher of the Bulgarian People,” had already been removed from its glass sarcophagus, then cremated and buried at Sofia’s Central Cemetery. Now the tomb had to go.

They blew up the mausoleum—or tried to—during a live broadcast on Bulgarian national television on August 21, 1999. It was a hot and cloudless day in the capital city of Sofia, perfect weather for a demolition. Ten years after the collapse of the country’s Communist regime there was still unfinished business to take care of. The mausoleum’s one and only occupant, the mummy of Georgi Dimitrov, “the Great Leader and Teacher of the Bulgarian People,” had already been removed from its glass sarcophagus, then cremated and buried at Sofia’s Central Cemetery. Now the tomb had to go. Bird omens once warned the ancients of the future. In Greece and Rome, for example, avian augury involved seers trained in the art of reading the flight of birds, who sought to make sense of a chaotic world through decoding messages from the gods. Since bird omens—or “auspices,” Latin for this kind of divination—often warned of disaster, ignoring or misreading them could be catastrophic. Ancient audiences watched tragedy unfold when hubristic rulers disregarded their augurs’ reading of these omens. (The two eagles that violently destroy a pregnant hare at the beginning of Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon, for example, forecast a Greek victory but prompt Agamemnon’s sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia, leading, in turn, to his murder at the hands of his wife, Clytemnestra.) The legacy of bird divination is etymologically evident in such words as augury, inauguration, and auspicious (from the Latin augur and auspex). Birds, it seems, continue to point to the future.

Bird omens once warned the ancients of the future. In Greece and Rome, for example, avian augury involved seers trained in the art of reading the flight of birds, who sought to make sense of a chaotic world through decoding messages from the gods. Since bird omens—or “auspices,” Latin for this kind of divination—often warned of disaster, ignoring or misreading them could be catastrophic. Ancient audiences watched tragedy unfold when hubristic rulers disregarded their augurs’ reading of these omens. (The two eagles that violently destroy a pregnant hare at the beginning of Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon, for example, forecast a Greek victory but prompt Agamemnon’s sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia, leading, in turn, to his murder at the hands of his wife, Clytemnestra.) The legacy of bird divination is etymologically evident in such words as augury, inauguration, and auspicious (from the Latin augur and auspex). Birds, it seems, continue to point to the future. By returning to the Victorian origins of the laws of thermodynamics, we can see how—and, perhaps, why—those laws have been broadly misconstrued and misapplied. In the 19th century, the first textbooks on the science of thermodynamics emerged from the work of Rudolf Clausius, in Berlin, as well as William Thomson (often called Lord Kelvin) and William Rankine, both in Glasgow. Studying how machines, such as steam engines, could exchange heat for mechanical work and vice-versa, these physicists learned of strict limits on efficiency. The best a machine could possibly do was to give up a small amount of energy as wasted heat. They also observed that if you had something that was hot on one side but cold on the other, the temperature would always even out. Their results were synthesized in the first two laws:

By returning to the Victorian origins of the laws of thermodynamics, we can see how—and, perhaps, why—those laws have been broadly misconstrued and misapplied. In the 19th century, the first textbooks on the science of thermodynamics emerged from the work of Rudolf Clausius, in Berlin, as well as William Thomson (often called Lord Kelvin) and William Rankine, both in Glasgow. Studying how machines, such as steam engines, could exchange heat for mechanical work and vice-versa, these physicists learned of strict limits on efficiency. The best a machine could possibly do was to give up a small amount of energy as wasted heat. They also observed that if you had something that was hot on one side but cold on the other, the temperature would always even out. Their results were synthesized in the first two laws: On 22 February 2002, Sgt Jacklean Davis was on a walk with her supervisor, Lt Samuel Lee, when Lee got a call from their commander at the seventh district in

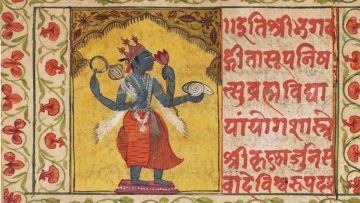

On 22 February 2002, Sgt Jacklean Davis was on a walk with her supervisor, Lt Samuel Lee, when Lee got a call from their commander at the seventh district in  The Upanishads, then, can hardly be called originary. They sound more like the latest in a series of disagreements; a great deal has preceded them, and reached a state of ossification before their arrival. Among what they challenge is a particular sense of causality regarding the relationship between creation and creator, which seems to have been extant when they were composed. Many traditions believe in a first cause, after which the universe comes into existence and before which there was nothing. The Upanishad’s conception of consciousness – “He moves, and he moves not”; “He is far, and he is near” – complicates the point of origin. Again, unlike Descartes’s belief that thought is both a product and a proof of existence, the Upanishad’s “What cannot be thought with the mind, but that whereby the mind can think” introduces an absence at the heart of thought. If thought can’t conceive whatever it is that produces it, then thought can’t be wholly present – a formulation that’s antithetical to the Cartesian proclamation. And since causality constantly reasserts itself as a default mode of thinking throughout history, the Upanishads remain, essentially, oppositional. They can’t occupy the space of established thought, being opposed to that space. Nor can one reduce either the Upanishads or the Gita in sociological terms to being “Brahminical” without losing sight of the fact that their language is critical-poetic – that is, they raise a critique through paradox and metaphor – rather than dogmatic or hieratic.

The Upanishads, then, can hardly be called originary. They sound more like the latest in a series of disagreements; a great deal has preceded them, and reached a state of ossification before their arrival. Among what they challenge is a particular sense of causality regarding the relationship between creation and creator, which seems to have been extant when they were composed. Many traditions believe in a first cause, after which the universe comes into existence and before which there was nothing. The Upanishad’s conception of consciousness – “He moves, and he moves not”; “He is far, and he is near” – complicates the point of origin. Again, unlike Descartes’s belief that thought is both a product and a proof of existence, the Upanishad’s “What cannot be thought with the mind, but that whereby the mind can think” introduces an absence at the heart of thought. If thought can’t conceive whatever it is that produces it, then thought can’t be wholly present – a formulation that’s antithetical to the Cartesian proclamation. And since causality constantly reasserts itself as a default mode of thinking throughout history, the Upanishads remain, essentially, oppositional. They can’t occupy the space of established thought, being opposed to that space. Nor can one reduce either the Upanishads or the Gita in sociological terms to being “Brahminical” without losing sight of the fact that their language is critical-poetic – that is, they raise a critique through paradox and metaphor – rather than dogmatic or hieratic. The secondary characters are extraordinary. As Penn State media professor Kevin Hagopian puts it in his film notes for the New York State Writers Institute, Odd Man Out is “festooned with gargoyles.” The crazed painter Lukey (Robert Newton) sees in Johnny’s suffering face the perfect model for a masterpiece of portraiture. With the bearing of a genteel bordello mistress, treacherous Theresa O’Brien (Maureen Delany) lets two of the bandits drink her whiskey in one room, while in another she informs the police of their whereabouts. Dim-witted Shell (F. J. McCormick), who collects birds and speaks in avian metaphors, discovers Johnny in a rubbish heap and relishes the reward he will get for turning in this bird with the wounded left wing. But Father Tom (W. G. Fay) persuades Shell that there is a greater reward than money and it is called Faith. When Shell wonders what Faith is, his roommate, a medical student, says, “It’s life.”

The secondary characters are extraordinary. As Penn State media professor Kevin Hagopian puts it in his film notes for the New York State Writers Institute, Odd Man Out is “festooned with gargoyles.” The crazed painter Lukey (Robert Newton) sees in Johnny’s suffering face the perfect model for a masterpiece of portraiture. With the bearing of a genteel bordello mistress, treacherous Theresa O’Brien (Maureen Delany) lets two of the bandits drink her whiskey in one room, while in another she informs the police of their whereabouts. Dim-witted Shell (F. J. McCormick), who collects birds and speaks in avian metaphors, discovers Johnny in a rubbish heap and relishes the reward he will get for turning in this bird with the wounded left wing. But Father Tom (W. G. Fay) persuades Shell that there is a greater reward than money and it is called Faith. When Shell wonders what Faith is, his roommate, a medical student, says, “It’s life.” A “

A “ Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away.

Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away.  Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that?

Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that? By now they are used to sharing their knowledge with journalists, but they’re less accustomed to talking about themselves. Many of them told me that they feel duty-bound and grateful to be helping their country at a time when so many others are ill or unemployed. But they’re also very tired, and dispirited by America’s continued inability to control a virus that many other nations have brought to heel.

By now they are used to sharing their knowledge with journalists, but they’re less accustomed to talking about themselves. Many of them told me that they feel duty-bound and grateful to be helping their country at a time when so many others are ill or unemployed. But they’re also very tired, and dispirited by America’s continued inability to control a virus that many other nations have brought to heel.  They had been public servants their whole careers. But when Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, two departing Obama officials were anxious for work. Trump’s win had caught them by surprise.

They had been public servants their whole careers. But when Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, two departing Obama officials were anxious for work. Trump’s win had caught them by surprise. To be sure, enlightened progressives were committed to science, positivism, and liberal democratic values—all of which the reactionaries rejected in favor of hierarchy and a highly traditionalist, and exclusively Catholic nationalism. It would seem to be a clear-cut struggle between the modernists and the antimodernists, but not as as Péguy saw it. He found the progressive faith in a scientifically driven and ever-improving future no more immanentizing, and no more modernist in its deepest aspirations, than the reactionaries’ vision. “These wrathful particularists,” Maguire explains, “often intimate a loyalty to older notions of transcendence—including religious faith and its avowal of abiding truths—but they conceive of that which transcends time only as an arrested immanence. They often present an amalgamated past as a unity…which now must be reinserted mechanically into the present, without creativity or surprise.” More ironically, some of the faux antimodernists (including the right-wing Action Française founder Charles Maurras, an admirer of the positivist Auguste Comte) also believed that “‘science’ would “confirm their particularism and prejudices.” Péguy’s critical stance toward both broad coalitions made him neither a modernist nor an antimodernist, Maguire argues, but something quite distinctive and instructive: an amodernist.

To be sure, enlightened progressives were committed to science, positivism, and liberal democratic values—all of which the reactionaries rejected in favor of hierarchy and a highly traditionalist, and exclusively Catholic nationalism. It would seem to be a clear-cut struggle between the modernists and the antimodernists, but not as as Péguy saw it. He found the progressive faith in a scientifically driven and ever-improving future no more immanentizing, and no more modernist in its deepest aspirations, than the reactionaries’ vision. “These wrathful particularists,” Maguire explains, “often intimate a loyalty to older notions of transcendence—including religious faith and its avowal of abiding truths—but they conceive of that which transcends time only as an arrested immanence. They often present an amalgamated past as a unity…which now must be reinserted mechanically into the present, without creativity or surprise.” More ironically, some of the faux antimodernists (including the right-wing Action Française founder Charles Maurras, an admirer of the positivist Auguste Comte) also believed that “‘science’ would “confirm their particularism and prejudices.” Péguy’s critical stance toward both broad coalitions made him neither a modernist nor an antimodernist, Maguire argues, but something quite distinctive and instructive: an amodernist. “I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.”

“I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.”