Ruth Ben-Ghiat in the New York Review of Books:

“As time went on, it became clear that the sickness was a feature, that anyone who entered the building became a little sick themselves,” wrote the journalist Olivia Nuzzi in March 2018 of the Donald J. Trump White House and those who serve it. For a century, those who have worked closely with authoritarian rulers have shown the symptoms of this malady: a compulsion to praise the head of state and a willingness to sacrifice one’s own ideals, principles, and dignity to remain in his good graces, at the center of power.

In his relationship with Republican political elites, as in other areas of endeavor, President Trump has followed the model of “personalist rule” used by leaders like Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Some of these rulers destroy democracy, and others, like the Italian politician Silvio Berlusconi, govern nominally open societies in undemocratic ways. Yet personalist rule always concentrates power in one individual whose own political and financial interests and private relationships with other despots often prevail over national interests in shaping domestic and foreign policy. Loyalty to this head of state and his allies, rather than expertise, is a primary qualification for serving him, whether as ministers or bureaucrats, as is participation in his corruption schemes.

While some authoritarians have political parties of their own creation at their disposal, Trump had no ready-made vehicle for his political ambitions before 2016. He had to win over the Grand Old Party to gain credibility and access to its machine and gain the collaboration of its elites.

More here.

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, a

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, a  Elena Ferrante

Elena Ferrante Nearly 60 years ago, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner captured one of the many oddities of quantum mechanics in a thought experiment. He imagined a friend of his, sealed in a lab, measuring a particle such as an atom while Wigner stood outside. Quantum mechanics famously allows particles to occupy many locations at once—a so-called superposition—but the friend’s observation “collapses” the particle to just one spot. Yet for Wigner, the superposition remains: The collapse occurs only when he makes a measurement sometime later. Worse, Wigner also sees the friend in a superposition. Their experiences directly conflict.

Nearly 60 years ago, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner captured one of the many oddities of quantum mechanics in a thought experiment. He imagined a friend of his, sealed in a lab, measuring a particle such as an atom while Wigner stood outside. Quantum mechanics famously allows particles to occupy many locations at once—a so-called superposition—but the friend’s observation “collapses” the particle to just one spot. Yet for Wigner, the superposition remains: The collapse occurs only when he makes a measurement sometime later. Worse, Wigner also sees the friend in a superposition. Their experiences directly conflict. IN 1953, ISAIAH BERLIN published his long essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” outlining his now-famous Oxbridge variant on there are two kinds of people in this world. He drew the title from an ambiguous fragment attributed to the ancient lyric poet Archilochus of Paros: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” Written with the aim of pointing out tensions between Tolstoy’s grand view of history and the artistic temperament that saw such a view as untenable, Berlin’s essay became an unlikely hit, although less for its argument about Russian literature than for its contention that two antithetical personae govern the world of ideas: hedgehogs, who view the world in terms of some all-embracing system, seeing all facts as fitting into a grand pattern; and foxes, those pluralists or particularists who refuse “big theory” for reasons either intellectual or temperamental.

IN 1953, ISAIAH BERLIN published his long essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” outlining his now-famous Oxbridge variant on there are two kinds of people in this world. He drew the title from an ambiguous fragment attributed to the ancient lyric poet Archilochus of Paros: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” Written with the aim of pointing out tensions between Tolstoy’s grand view of history and the artistic temperament that saw such a view as untenable, Berlin’s essay became an unlikely hit, although less for its argument about Russian literature than for its contention that two antithetical personae govern the world of ideas: hedgehogs, who view the world in terms of some all-embracing system, seeing all facts as fitting into a grand pattern; and foxes, those pluralists or particularists who refuse “big theory” for reasons either intellectual or temperamental. Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups.

Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups. A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of

A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of  That the Latin name for the caper flower, Capparis spinosa, is related to the Italian word capriolare (meaning ‘to jump in the air’), is a droll enough visual/verbal play to suggest that Titian is intentionally teasing us with the placement of the prickly perennial plant directly under the bouncing Bacchus. But it is the plant’s medicinal use, since antiquity, as a natural carminative (or remedy for excessive flatulence) that reveals the artist is truly letting rip with some mischievous fun. In the context of Titian’s carefully deployed caper, Bacchus’s explosive propulsion from his seat appears more wittily, if crudely, choreographed by Titian, who demystifies the lovestruck levitation by providing us with a more down-to-earth explanation for the cheeky lift-off. In Titian’s retelling of Ovid’s myth, Bacchus has been hoisted by his own pungent petard, as Shakespeare, who likewise loved toilet humour, might have said.

That the Latin name for the caper flower, Capparis spinosa, is related to the Italian word capriolare (meaning ‘to jump in the air’), is a droll enough visual/verbal play to suggest that Titian is intentionally teasing us with the placement of the prickly perennial plant directly under the bouncing Bacchus. But it is the plant’s medicinal use, since antiquity, as a natural carminative (or remedy for excessive flatulence) that reveals the artist is truly letting rip with some mischievous fun. In the context of Titian’s carefully deployed caper, Bacchus’s explosive propulsion from his seat appears more wittily, if crudely, choreographed by Titian, who demystifies the lovestruck levitation by providing us with a more down-to-earth explanation for the cheeky lift-off. In Titian’s retelling of Ovid’s myth, Bacchus has been hoisted by his own pungent petard, as Shakespeare, who likewise loved toilet humour, might have said. The original Garden of Emptiness, Kyle Chayka explains in his pugnacious whistlestop tour of minimalism, is to be found in the 16th-century rock garden of the Kyoto Zen temple Ryoan-Ji. Chayka journeys to this sacred spot in search of the philosophical minimalism that has been obscured by today’s commodified decluttering. His book, which ranges from the Stoics and Buddhism to Mies van der Rohe, is a rebuke to the Shintoistic declutterer Marie Kondo, whose bestselling Netflix-powered KonMari method urges us to retain only those possessions that ‘spark joy’ and to practise such techniques as folding trousers vertically and not – heavens! – horizontally. Chayka warms to Donald Judd’s Plexiglas, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Brian Eno’s ‘Discreet Music’. He is irked by minimalist hipsters’ all-grey uniforms and the solipsistic sensory deprivation of the Soulex company’s amniotic ‘float spas’. But such businesses are booming. In hard times, many go minimal by default, yet others pay handsomely for the ultimate postmodern lifestyle commodity, which, Kayla observes, they can of course never possess: nothing.

The original Garden of Emptiness, Kyle Chayka explains in his pugnacious whistlestop tour of minimalism, is to be found in the 16th-century rock garden of the Kyoto Zen temple Ryoan-Ji. Chayka journeys to this sacred spot in search of the philosophical minimalism that has been obscured by today’s commodified decluttering. His book, which ranges from the Stoics and Buddhism to Mies van der Rohe, is a rebuke to the Shintoistic declutterer Marie Kondo, whose bestselling Netflix-powered KonMari method urges us to retain only those possessions that ‘spark joy’ and to practise such techniques as folding trousers vertically and not – heavens! – horizontally. Chayka warms to Donald Judd’s Plexiglas, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Brian Eno’s ‘Discreet Music’. He is irked by minimalist hipsters’ all-grey uniforms and the solipsistic sensory deprivation of the Soulex company’s amniotic ‘float spas’. But such businesses are booming. In hard times, many go minimal by default, yet others pay handsomely for the ultimate postmodern lifestyle commodity, which, Kayla observes, they can of course never possess: nothing. In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better.

In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better. Soon after the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan

Soon after the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan  This, Clive James’s final book, is a collection of his writings on Larkin and his work. James takes his title from the final words of Larkin’s ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ (1959). The ninety four pages, which include copies of one manuscript letter and two typed letters from Larkin to James, don’t offer very much book for your money, but you do get Clive James, who’s always good value. His explanation of why Jack Nicholson is the only Hollywood actor appropriate to play Larkin onscreen justifies the price of admission.

This, Clive James’s final book, is a collection of his writings on Larkin and his work. James takes his title from the final words of Larkin’s ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ (1959). The ninety four pages, which include copies of one manuscript letter and two typed letters from Larkin to James, don’t offer very much book for your money, but you do get Clive James, who’s always good value. His explanation of why Jack Nicholson is the only Hollywood actor appropriate to play Larkin onscreen justifies the price of admission. In July 1925, Margaret Mead, a doctoral student at Columbia University, set off on a cross-country train journey with a young faculty member, Ruth Benedict. Mead was bound for the west coast and then American Samoa, her first fieldwork expedition as a junior anthropologist. Benedict was stopping in New Mexico to study myth and ritual in the Zuni Pueblo. The journey took them through Ohio to Illinois, across the prairie, then south toward the deserts. It was the longest the two of them had ever spent together, certainly the longest without their husbands in tow.

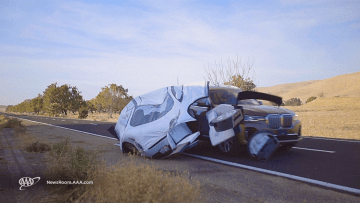

In July 1925, Margaret Mead, a doctoral student at Columbia University, set off on a cross-country train journey with a young faculty member, Ruth Benedict. Mead was bound for the west coast and then American Samoa, her first fieldwork expedition as a junior anthropologist. Benedict was stopping in New Mexico to study myth and ritual in the Zuni Pueblo. The journey took them through Ohio to Illinois, across the prairie, then south toward the deserts. It was the longest the two of them had ever spent together, certainly the longest without their husbands in tow. Recently, researchers at MIT published a study that looks into autonomous vehicle mobility, employment and policy. The research found that self-driving vehicles will happen later than sooner.

Recently, researchers at MIT published a study that looks into autonomous vehicle mobility, employment and policy. The research found that self-driving vehicles will happen later than sooner. It is becoming clear that many of our nation’s children could be attending school from home for this school year and possibly longer. If educators and families aren’t empowered with the right support and tools, this will evolve from an education crisis to an education catastrophe.

It is becoming clear that many of our nation’s children could be attending school from home for this school year and possibly longer. If educators and families aren’t empowered with the right support and tools, this will evolve from an education crisis to an education catastrophe.